Before Nick of Time became perhaps the biggest Cinderella story in Grammy history — as well as the cement to Bonnie Raitt’s now-unshakeable legacy as a singular song interpreter and advocate for the blues tradition, and the soundtrack to so many ‘90s babies’ childhoods — it was a last-ditch effort to salvage the career of a cult-favorite artist who had just hit rock bottom.

“Nobody expected it to sell well,” Raitt says now. “They just said, ‘We’re not going to pay a lot of money for you, so just make a record that you want.’”

The record she wanted, as it turned out, was an understated, beautiful expression of both personal and artistic self-assurance. Nick of Time’s stripped-down but polished sound wasn’t revolutionary to her fans, who’d long appreciated Raitt’s combination of remarkable musical talent and no-nonsense attitude. But to mainstream listeners, her ability to package an impressively wide array of blues, country, R&B and pop songs into one seamless, mostly analog album was a welcome sea change from the heavily produced, homogenized hits of the era.

It was Raitt’s 10th studio album, but her first to crack the Billboard 200’s top 25. Over nearly 20 years, she’d gone from prodigy college dropout to undeniable live performer, whose recorded catalog was filled with uncompromising roots music and major label attempts to channel her obvious gifts into pop success.

And at the very moment when that seemed the least likely, the impossible happened: the right artist made the right album at the right time. A critical darling who had flirted with the musical mainstream for decades made a classic paean to the trials and benefits of aging that was bold and approachable at once. And its biggest hit wasn’t even the one whose music video co-starred a hunky Dennis Quaid and went into heavy rotation on the then-nascent VH1.

The narrative was obvious: The press drooled about the then-39-year-old’s “comeback” from substance abuse and obscurity, and was agog that a woman “of a certain age” — as some outlets put it in an attempt at diplomacy — might reach a wide audience singing about her own life experience.

“It actually didn’t bother me at all,” Raitt, now 69, says with characteristic frankness. “Especially because the title song is about exactly that. A lot of the circumstances besides age came together to bring that album such wide attention, but I’ve never minded talking about my age. Something I’m proud of.”

The Recording Academy didn’t mind either, sending Raitt home with all four Grammys she was nominated for at the 1990 ceremony, including album of the year — which she accepted in stocking feet after breaking a heel during one of her many trips to the stage. The album has since sold over five million copies, and more importantly, revitalized the career of one of America’s most important roots musicians.

Looking back, the album wears its age almost as well as Raitt herself — both, it seems, are timeless.

“I have so many people to come shows with their mothers, or with three generations, saying ‘My mom played this album for me in the car when I was little, and you’re one of the artists that means the most to us,’” says Raitt. “It means so much to me that Nick of Time resonated with so many women, especially. I never expected it to have the response it did.”

*******

“Out of the worst thing came the best thing.”

After failing to get the kind of hits that might have made her seven-figure deal with Warner Bros. seem worthwhile to label execs, Raitt was dropped unceremoniously by the label. She fell into a rough patch during which her self-described “road-dog” lifestyle began to catch up with her. Producer Don Was, still looking for his big break, was going through similar burn out.

Bonnie Raitt: I had a record scheduled to come out in ’83 and a tour with Stevie Ray Vaughan. Just as we were starting to do promo for it, Warner Bros. dropped me, Van Morrison, T Bone Burnett and Arlo Guthrie. Suddenly the bean counters were running the company and said, “They’re dead weight, they don’t have hit singles.”

Don Was (Nick of Time producer): In 1986, I hit rock bottom. I was producing records unsuccessfully, including for this English guitar band that the record company wanted us to put synthesizers all over.

Raitt: Getting dropped derailed my touring plans, and put my band out of work. I had a love affair that was going sour partly because of the business relationship that was enmeshed in it. The record company and romantic issues evidenced themselves in self-medicating — I was really furious, and I had to stay on the road. Luckily I’m one of those people who can tour with just a bass player and still make a good living.

Was: I was flying out to L.A., and left the multi-tracks of one of the band’s songs in a New York taxi with no safety copy. In the end I was able to recover them, and all I had to do was move the session back one day. But in that moment, I thought I’d fucked up so badly. I think I had the advance copy of Peter Gabriel’s So, and I kept playing “Don’t Give Up” over and over on my Walkman on the way to the Newark airport, crying — I just felt like such a schmuck.

Raitt: I had kind of puffed up, and I was going to make a record with Prince. I was like, “I’ve gotta lose some weight, because if we make a video this is not going to look good.”

Danny Goldberg (Raitt’s manager): She went to Minneapolis and recorded at least two songs with him, and she was pretty excited about it — I mean he was fucking Prince, at the peak of his powers — but my heart sank when I heard them, because it wasn’t Bonnie Raitt. They were Prince records with Bonnie Raitt singing on them. Nobody was excited about it, and I was kind of relieved when it went away.

Raitt: Just out of wanting to be healthier and look better, I decided to quit drinking for a while and I really liked it. Next thing I knew, I’d lost 20 pounds and was digging being sober. ’86 was the downside, and ’87 was when I turned things around and got some help. I was really rejuvenated.

Was: Because that session moved back a day, I got to a studio in L.A. called The Complex on a Sunday instead of a Saturday. Because I was there on a Sunday, Bonnie was there, working in another room. That’s how I met her. I wouldn’t have met her if I hadn’t lost that master tape. It’s a darkest before dawn kind of thing — out of the worst thing came the best thing.

“We were going to work together whatever label we were on.”

Raitt and Was first worked together a year after that accidental studio meeting. Was and his band Was (Not Was) invited her to sing on a cover of “Baby Mine” from Dumbo for a Disney-themed compilation produced by Hal Willner called Stay Awake, which was released in 1988.

Goldberg: We just had to keep Bonnie in the conversation, and so any compilation or benefit, we said yes to. [The Disney compilation] got zero attention, but we knew how great this song was. When we finally signed to Capitol, we said “Please listen to this thing Don Was did with her.”

Raitt: We were going to work together whatever label we were on.

Was: I had a really funky little studio in my house. She didn’t have a record deal at the time, so we just started making demos for what became Nick of Time there. It took a while.

Raitt: He came to see me play at one of the acoustic gigs with my then-bassist Johnny Lee Schell and said, “This format really showcases how different and special you are. If you can make the song work just playing it for me like that — stripped-down — that’s how we should pick the songs. Whatever works without needing a full band.”

Was: No matter how cool a track we might eventually make, it had to work with just her alone. It was just about hearing her unadorned voice — everything else would augment that. So we demoed a lot of songs to get to the ones that were on Nick of Time.

I’ve worked with a lot of folks, and I don’t know anybody in the world who’s a better singer than Bonnie. If you can just imagine her sitting three feet away from you playing guitar or piano, and you’re hearing that beautiful voice coming through your headphones… I don’t know that it ever gets any more satisfying than that experience.

Goldberg: It was all about getting her a new label, and that was not easy because she’d been around for 15 years or so. A lot of people in the business felt that her moment commercially had come and gone. I kept count — 14 people passed.

Tim Devine, A&R for Nick of Time: People think, “Well of course you signed Bonnie, it was so obvious — who wouldn’t do that?” I have to remind them that there was nobody interested in signing Bonnie Raitt in 1988. When I went to sign her, [Capitol A&R] Tom Whalley said “Over my dead body.” I had to go over him to [Capitol Records president] David Berman to get her signed.

Goldberg: The last choice was Capitol, because at that time among the majors, they were really cold. I think the budget was $150,000, which was standard at that point for what a new artist would get — even though she was by no means a new artist.

Devine: We made a very modest deal, a deal that could break even just based on her fanbase alone — so there was never this pressure in the studio to create big top 40 singles. Ironically, that’s what made the album as special and as ultimately successful as it was. It was all natural, nothing was forced.

Goldberg: We had a low budget, so there was no chance of getting an expensive producer. I don’t remember it being difficult [to get the label onboard with hiring Was], but Don wasn’t on anyone’s list in those days as a producer.

Was: Her managers took me out to eat at one point, and said, “Look, it’s great that you want to work with her, but if it comes down to it and a record company comes along and insists that she have a real producer, we’re going to throw you under the bus.” That’s an actual quote. But we’re all friends now.

James “Hutch” Hutchinson (bass): I think because there weren’t any great expectations, nobody was looking over our shoulder. The label was letting us do what we wanted to do. It sort of set a precedent for Bonnie’s later records — they gave her and Don free rein after that.

Raitt: People had a reservoir of respect and affection for me, and thought I had kind of gotten a raw deal. Plus, I think the record business changed in the late ’80s — people like Tracy Chapman and Edie Brickell and Robert Cray and the Fabulous Thunderbirds had hits.

I was like, “If they’re doing this kind of roots music and it’s getting on adult contemporary radio and college stations, I’m gonna come back and make a record and actually have a shot at getting some airplay again.” Which was thrilling. Having a new label that cared, having the radio climate change, getting sober and finding Don Was all came together in a kind of kismet of timing. It was great.

“She just got all her great friends together.”

Nick of Time was recorded in 1988, mostly over the course of a week at Ocean Way Recording (6000 Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles — today it’s known as EastWest Studios). Raitt and Was had whittled down the tracklist in the demo process, and knew they wanted to use those bare-bones tapes as the basis for the album. Their extensive preparation plus the tight budget for studio time meant the recording process itself, as the musicians remember it, was speedy and almost effortless.

Was: We had two goals. We knew the music was as unfashionable as could be. So we just thought, let’s just try to make something we’re gonna be proud of in 25 years. The other goal was to make the [label’s] money back, so that we could stay in the game and do another album.

Goldberg: As I remember it, the whole thing was, “Can we get a gold album?” She’d only had one before. That was the goal.

Was: It came together really quickly, and not when it was supposed to. But [drummer Ricky Fataar] was in town from Australia, and we could get all the people we wanted in a room together like, next week. She just got all her great friends together. I don’t know anyone who doesn’t love her.

Raitt: I pick them because I know we feel the same way about the music, and it went really well because they weren’t strangers to me.

Was: We’d done the preparation with the demos, we knew what we wanted. I think we booked a studio for a week, and at the end of the week we had the album.

Raitt: For me, the vibe to go for is as live and uncorrected as possible. Minimal rehearsal. We get the sounds, we set up the equipment, it’s the same band for five days — maybe different keyboard or guitar players come in on different songs. We cut about two tracks a day, and I try to get the vocal on the first take and then do two or three takes total. It’s a formula I’ve used ever since.

Ricky Fataar, drummer: There was never really much discussion. She had demos of everything, and there was a boombox in the studio. We’d listen to the different tunes, play them a few times and put them to tape. There weren’t any charts or anything like that, we just basically learned them by ear.

Ed Cherney, engineer: It never felt like work. The hang… we don’t make records like that so much anymore, with everybody just in the room playing together.

Was: This was an underdog record, and everyone was determined for her music to be heard. They went way beyond the call of duty, and I think you can hear that in the playing. There’s nothing perfunctory coming out of anybody.

“It was the ‘nick of time’ for all of us, you know?”

One of a select few songs in Raitt’s catalog that she wrote herself, the personal and intimate “Nick of Time” would become the album’s defining track. The opening verse’s “friend” was a real friend of Raitt’s who was actually struggling with how to cope with a ticking biological clock, and the song also featured her singing about her own parents (“I see my folks, they’re getting old…”)

Raitt: At the time I wrote it, “Nick of Time” wasn’t anything I thought was going to be singled out. But the most excited and vulnerable I felt was to play that demo for Don. He was a fan of soul music — I love that Philadelphia International sound and there’s a lot of that in the rhythm section on “Nick of Time,” which I wrote the piano part to.

Was: She played this crazy Roland electric piano on the demo — it was a sound that we knew we couldn’t use on the record because it was very hollow and kind of digital, but it did complement her voice well. When we got to the studio, we tried doing [the opening line] on a Rhodes and other instruments — we tried everything, but nothing layered as well with her voice. So we had to find this funky old synth, and that’s the thing that’s on the record.

Cherney: To this day, nothing sounds like that song. You know in one measure, that’s “Nick of Time.” If you can do that, you’re in business.

Was: When she played it for me, that thing about your parents getting old… I was going through that, and you start thinking about it a little more clearly at that age. It was eloquent, beautiful poetry.

Goldberg: I remember putting on a cassette demo of “Nick of Time” in my car — I started crying when I heard it. I don’t think anybody knew how important that song was going to be, but it had a vibe to it that was special.

Raitt: I just felt like it was a really fitting title because of its double edge. Making those decisions and life changes in the nick of time, but also just the nick of time — the fact that my friend had to decide if she would split up with her long time mate, or if she wanted to have a child. Those costs you pay of getting older.

Was: I think it’s one of the most radical, rock and roll songs that anyone’s ever come up with. No one, male or female, had the courage to talk about turning 40. Everyone had to pretend like they were still 18 and smoking in the high school bathroom. She addressed a mature theme without compromising or affectation. It was just a brave record to make.

Cherney: It was the “nick of time” for all of us, you know? It informed us as to what the record really should be.

Raitt: When that album came out and so many people wrote about that song specifically, I think it certainly put a little more pressure on [the man whose indecision inspired the first verse]. She got pregnant and they got married — the kid is great.

“I remember it being very flirtatious.”

“Thing Called Love” was the album’s first single, a cover of a John Hiatt song he had released on his own 1987 album Bring The Family. The rollicking, sassy track was sent to radio in February 1989 and peaked at no. 11 on Billboard‘s Mainstream Rock Songs chart that May — but more than radio, the catalyst for its success was a crowd-pleasing video featuring a famous co-star that went into heavy rotation on the then-brand new station VH1.

Raitt: I was totally selfish — I just wanted to play it every night. I love the lyrics, I love the playfulness, I love the John Lee Hooker shuffle beat. Of all the songs I’ve played over the years, it’s one of my absolute favorites.

Was: “Thing Called Love” was the hardest song to cut. The feel of it is just so raw and explosive on John Hiatt’s record — it’s peculiar even to people who played on it. And we could not figure out what the fuck [drummer] Jim Keltner was doing. We just kept listening to it over and over — in the end we just did our version of it, you couldn’t recreate what happened there.

Cherney: It may have taken me five or six times to nail the mix on that, because where it sounded great was on the head of a pin. It was that delicate.

Devine: “Thing Called Love” was the first single we released, because we wanted to take advantage of the rock market for her before coming out with some of the softer songs. On the other hand, I don’t think anybody even thought we were going to get a second single.

Goldberg: MTV had just created the VH1 channel, and they didn’t exactly know what they were going to do with it. It’s counterintuitive now, but they were thinking they would go to an older audience. Within the first month or two of VH1’s launch, we give them the video for “Thing Called Love” and she had Dennis Quaid… VH1 gave her the kind of exposure that was hard to get on radio.

Was: We probably all owe Dennis Quaid thanks. He was as important a component in spreading the gospel of this record as anybody, and he did it for Bonnie.

Dennis Quaid: When I was in my first year of college, her first album was my favorite record. After I did [1986’s] The Big Easy, I think I met her through the Neville Brothers. Also some of her touring band played in my band.

It took a day to film the video, at the Canyon Club [in Los Angeles]. That was my music video debut. It’s kind of hazy, because I was in my… party time in the late ’80s. But I do remember everything. It was so easy to do, and fun. It’s very ’80s to look at, in a really good way. I’d just finished [Jerry Lee Lewis biopic] Great Balls of Fire, so I still had my Jerry Lee shock blonde hair.

Raitt: I hadn’t seen the video in a while, and then I saw it recently — he was just so sexy in it. It brought back how fun that video shoot was.

Quaid: I remember it being very flirtatious.

Joan Myers (publicist): That video! She’s a big flirt.

Quaid: At the time that it came out, it was like I had a hit movie or something. Probably more people saw that video than five of my movies put together. I still get asked about it, even on movie junkets.

“Pissed off as well as vulnerable”

The album’s other two singles, “Love Letter” and “Have a Heart,” were both written by Bonnie Hayes, who is now the chair of the songwriting department at the Berklee College of Music. The latter became the album’s biggest hit, peaking at no. 3 on the Adult Contemporary chart on April 14, 1990 and No. 49 on the Hot 100 the week before. The pop-reggae song was lilting and gentle — with the exception of its famous opening line.

Bonnie Hayes, songwriter: I wrote them both within a few months of each other. “Have a Heart” was supposed to be for Huey Lewis, who was working on [1988’s] Small World which was — at that point — a reggae album. I asked my brother Kevin Hayes, who is the drummer in Robert Cray’s band, to come over and program some beats for me because I didn’t know how to program a reggae beat. Then I wrote the songs to those beats.

I wound up wanting them for myself, but Bonnie heard them from my publisher. She came to see me and said, “I will get on my knees — I want these songs.” I was like, “No need! You may have them.” [Laughs.]

Raitt: To this day, I think “Have a Heart” has one of the greatest opening lines I’ve ever sung. These mothers would come up to me and say, “Just when I’m trying to teach my Nick of Time toddler to be polite, I want to play this song — and then they’re in the car going, ‘Hey, shut up!’”

Was: It’s as good as “The warden led the prisoner down the hallway to his doom.”

Raitt: I thought it was so lyrically sophisticated in that she’s pissed off as well as vulnerable. That thread goes through a lot of my music.

Hayes: My boyfriend who I lived with was addicted to drugs, and I had to leave him and move out. Then I fell in love with someone else, like, right away. “Have a Heart” was initially supposed to be a joke, the way people say, “C’mon, have a heart, give me a break, get off my case.” I kept trying to write this funny song, but my heartbreak over what had happened with my boyfriend just kept squirming its way in. Finally I realized the song was not going to be what I had intended. Instead, it’s like, just freaking tell the truth. Don’t make me into a patsy.

So “Have a Heart” is a goodbye song, and “Love Letter” is a hello song. I just think it’s funny that they ended up on the same record, because it’s like the beginning and the end.

Raitt: I’m a huge fan of Al Green’s music, and I love the way “Love Letter” that recalls that. Plus, to be able to play slide on that kind of a groove…Bonnie Hayes has a very innovative way of updating some of the classic R&B and reggae feels.

Hayes: “Love Letter” is saying, “I’m in charge” — which I love. It’s about that moment where you don’t really know whether it’s actually happening or it’s all in your mind. In a way it’s kind of creepy, because it’s a woman sitting in front of a guy’s house… but that night actually happened, right before I got together with the man who would later become my husband.

Cherney: When the band comes in the control room to hear a song again and wants to turn it up, I know that something really cool is happening. Instead of like, “What are we having for lunch?” With “Love Letter” it was like, “Let’s hear that again!”

Was: The attitude of the two Bonnie Hayes songs really encapsulates a nice part of the spirit behind Bonnie Raitt. She didn’t care whether she wrote a song or not, but it had to reflect who she honestly was and what she was going through. She didn’t have to act — she would Stanislavski everything.

Hayes: All of those songs were given a gift, including mine, when she chose to cover them. She puts the ache into everything. She never leaves anything in her pocket, which I just really admire.

Was: It’s very powerful imagery for her to be a strong and equal partner to somebody and say, “Don’t lie to me, don’t bullshit me, just be for real and as strong as I am.” That wasn’t necessarily what women were supposed to be singing about in rock and roll, and there’s a lot of that on this album. “Nobody’s Girl,” “Have a Heart,” “I Will Not Be Denied,” “I Ain’t Gonna Let You Break My Heart Again” — all of them, really.

You have to get older to be sick of the bullshit and say, “I’ve had enough of this, here’s how it’s gotta be. I’m not asking anything of you that I won’t give, but you’ve gotta stand up and meet me.” And it’s all real.

“It’s a different woman that picked the songs on Nick of Time than picked the ones on my first album.”

The album cuts on Nick of Time show Raitt’s range, from melancholy ballads (“Cry On My Shoulder”) to rough-and-tumble blues (her own composition, “The Road’s My Middle Name”). They also feature some of the album’s biggest names: Graham Nash and David Crosby sang backup vocals on “Cry On My Shoulder,” Herbie Hancock accompanied Bonnie on piano for “I Ain’t Gonna Let You Break My Heart Again,” and The Fabulous Thunderbirds supplemented her band on “The Road’s My Middle Name.” The end result was fluid, creating an album that was bigger — and more successful — than the sum of its parts.

Michael Ruff, songwriter: I think I gave her a cassette with some songs on it, and “Cry on My Shoulder” was on the B-side and I didn’t know it — it wasn’t really one of the songs I was thinking of giving her. And of course she ended up liking that one.

I just dedicate it to my wife every time we hear it. It’s a very simple friendship song. When you look back, what really counts is just showing up. We only have so much time, so let people know: “Ok, I’m here — as long as I can be, I’ll be here for you.”

Graham Nash: Bonnie called me up and wanted me and David [Crosby] to sing on it because, of course, David and I have a reputation for being able to sing harmony pretty good.

Was: The thing I remember most is just being gobsmacked when Crosby and Nash came in. I just kept turning to Ed Cherney and saying, “He was in the Byrds, man!”

Nash: Normally, when Crosby and I are singing with other people, we meet beforehand and go together — but this time, Crosby went to the studio early and stole the high part. So I had to sing beneath Bonnie and David, which was unusual for me, but I thought we did a pretty good job. The vocal blend sounded beautiful, even with me on the bottom instead of at the top. And it’s such a beautiful song too.

Raitt: The angel choir, you know? They were so great to come in and do that.

Nash: It was a very quiet session, and the lights were down low. It was romantic lighting — Bonnie is a very beautiful woman, but we have never been together at all. But it was romantic lighting and a quiet and beautiful song, and a few minutes of absolute ecstasy.

Raitt: “Nobody’s Girl” is a masterpiece. Some of my favorite songs I’ve ever recorded are written by men — men who are highly conscious of such wonderful versions of what modern men could be.

It has a complexity in the lyric that is so artful — Larry John McNally is one of my favorite writers ever. He’s an undersung, underrated brilliant artist, and he’s constantly putting out records and should be appreciated more than he is.

Was: We’d cut it and everyone had gone home, and we were feeling like, “Shit, we didn’t get this.” We were losing the story. I just remember saying, “Give me five minutes.” I went to the board and muted all the instruments except for her and her guitar. And then it was like, “Oh, it’s back.” We almost lost that one.

Raitt: “Too Soon To Tell” is the only out and out country song I’ve ever recorded, besides the songs I’d done for the Urban Cowboy soundtrack. That pedal steel is just so exquisite — it’s kind of a classic soul ballad with the country twinge to it. I loved it on a Mike Reid solo album, and it was so fortuitous because that’s one of the reasons he sent me [1991 smash] “I Can’t Make You Love Me.”

John Jorgenson (guitarist on “Too Soon To Tell”): After her success, everyone in Nashville started wanting that kind of slide [guitar] on their records. Listen to country records from 1990 or 1991 on, and you can hear a lot more slide and lap steel — and I would attribute that to Bonnie’s success. Now it’s just normal.

Was: I’d never met Herbie Hancock before that session at Capitol Studio B, and he was a lifelong hero of mine. It was one or two takes — I think we did one that was a little long, so we did a shorter one.

Raitt: I’d never recorded with Herbie before, or done anything that exciting as far as being, “On your mark, get set, go” with one of the great geniuses of forever. It was a very stretching and exciting and hairy and rewarding session.

Was: It was a great moment, that session. He has the best ears, and he knows, man. He knows who’s for real, and he had total respect for her.

Raitt: The song is just a jewel. I mean every word I sing, and I pick songs where I have to really mean every lyric — and this one I had been meaning for a long time [laughs]. I’d been wanting to record it for at least 15 years.

Was: The only fixes we had to do on the vocal for “I Ain’t Gonna Let You Break My Heart Again” are the couple of lines where she started crying while we were doing it.

Was: She had a gig at the Austin Opry House, on a bill with Stevie Ray Vaughan, Jimmie Vaughan and The Fabulous Thunderbirds. She was like, “We’re going to have them all right there, and Arlyn Studios is next door to the venue.” It was Bonnie’s call [to record “The Road’s My Middle Name” there], and it was really a wise choice — it feels so live. We mostly used the room mics, and you really get a sense of being in that room at Arlyn.

Raitt: My friends The Fabulous Thunderbirds were the best modern version of what I loved about Muddy Waters’ classic bands in the ‘50s and ‘60s. They knew how to play that groove in a way that wasn’t corny, or the typical “white guys playing the blues” kind of a thing. I’m fully admitting that I’m from Los Angeles and last time I looked, I was still white. But if you understand what makes blues funky, and what makes some of those original, classic recordings work…

Was: One of the things that makes that album appealing, I think, is that it’s a little like The Beatles’ White Album. Every song is really different, and the thing that holds it together is the strength of Bonnie as an artist.

Raitt: I guess the only thread you could put between “Nobody’s Girl” and “The Road’s My Middle Name” would be the fact that I like them both. I don’t mean to sound egotistical. It makes total sense to me to put those songs together, but I don’t know if anybody else would.

Was: Her sensibility unites everything. Texturally, though, there’s a wide range.

Raitt: I have a certain point of view as a woman about what I will put up with and what I won’t. It’s a different woman that picked the songs on Nick of Time than picked the ones on my first album, when I was 21 — even though I had a lot of bravura and a feminist point of view early on. They speak to the personal politics of how you take responsibility in a relationship for asking for what you want, and for leaving when it’s not working out. When you’re a young woman, that often doesn’t happen.

But this generation has a lot better shot at standing up for what they want before they get in a bad relationship. The roles of men and women have changed so fundamentally that you can actually delight in the differences now, instead of being tied down by them.

“I thought, ‘Oh great, another fan.’ It was Bette Midler.”

The response to the record was a slow burn — though it sold more than expected from the start thanks to a slew of glowing press and Raitt’s core fans, that was only in comparison to the label’s extremely conservative projections. But instead of peaking early, the album kept building and building, steadily defying the expectations of everyone from the label to Raitt herself.

Fataar: When you heard it back in the control room, I thought it was pretty bloody special. But nobody imagined that it would go through the roof like it did.

Thom Duffy (Billboard editor): The production was so much more accessible to a mainstream pop listener, and yet Bonnie’s voice was so authentic and true to what her fans had loved for years, and then the songwriting was just spectacular throughout. As a fan, you were like, “This is it.” But as someone in the music trade, you could never have predicted.

Devine: I could barely get them to do a poster for her. I had to go to the president of the company and get him to approve full-page ads in Album Network and Billboard because my marketing team didn’t think it was going to be worth it. That was going to be the end of the marketing campaign — a poster, an ad and a video.

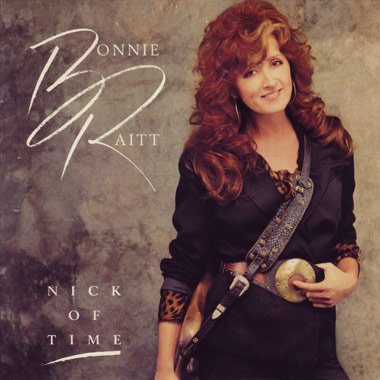

Deborah Frankel (photographer for the Nick of Time cover): The only thing she said was that she did not want a clock in the picture. What did some designers send me after the meeting where she had said, “I don’t want a clock”? They sent me an idea with a clock!

Was: All the people who didn’t want to give her a record deal had severely underestimated the devotion of her core following. After basically the first week, her record was in profit — we hit the sales goal.

Myers: Bonnie’s personality and sincerity just won people’s hearts, in addition to her music. There was nothing ever pretentious about her. Part of me is like, how hard did I really work? It was all the right things at the right time, just falling into place. The stars aligned, everything just fit into place.

Nash: Everybody in the business knew how great Bonnie Raitt was, and it was only a question of time before everybody else knew it.

Myers: Bonnie didn’t realize how revered and famous she was. I remember after her performance at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, she wanted to go to the gospel tent. I told her we couldn’t just walk there on our own, that we needed security. And she said, “No, we can” — and we couldn’t. People were stopping her. In the gospel tent, there was a woman behind her who was trying to get her attention, and I thought, “Oh great, another fan.” It was Bette Midler.

Duffy: “Nick of Time” saw a singer with a long history among passionate fans singing to an audience that had not really been reached in that way by someone who they trusted. The core audience was brought in by the new songs, and the pop audience was brought in by the new sound.

Was: We had hit this moment in history when people had had enough sequenced synthesizer music and wanted something real and organic. And there we were.

“Mom, I won — no no, all of them.”

For Raitt, who’d gone into the album just hoping to break even and make some music she could tour on, it was truly an honor just to be nominated for her first non-genre Grammy, album of the year. But she won — beating Don Henley, Tom Petty and even the supergroup the Traveling Wilburys — and swept every category she was nominated in, becoming one of the most dominant forces in early-’90s adult pop in the process. Nick of Time was followed by two more Don Was-produced multi-platinum albums, 1991’s Luck of the Draw and 1994’s Longing in Their Hearts, which made Raitt a commercial powerhouse — one also widely recognized for her unimpeachable artistry.

Was: I remember the A&R guy Tim Devine came into the studio while we were recording and said, “You got a tux?” I said “No, of course not.” And he said, “You’re gonna need one for the Grammys.” My first reaction was that I wanted to punch him. Like, get out of here. Just say you like the record. But he proved prescient in his assessment. [Laughs.]

Goldberg: The whole thing beforehand was, would she win one? One would be amazing. I don’t know if anybody I spoke to thought it was possible for her to win album of the year. That was not considered something to hope for, or even think about.

Cherney: It came out of nowhere — this was just a little record. No one was expecting that at all. I may have cried. I may have just broken down and cried.

Goldberg: Because it was on the West Coast, I think it was a delayed broadcast in California but live in New York. I remember seeing her right after the show on the phone with her mother, and she was saying, “Mom, I won — no no, all of them.”

Duffy: She’d been accompanied to the Grammy awards by her father. She told me that at one point he leaned over to hug her, and she could feel him starting to sob — she said that at that point, she just lost it.

Raitt (to Billboard in 2016): I did not expect at all to win that many. Every time I won I’d go backstage to talk to the press and there was another award, so it was getting more and more surreal as the awards were piling up. So my memories of that night are as close as you can get to Cinderella.

Cherney: For Don and Bonnie and I, it was really the first time we’d had that kind of success. Your first successes are the best, and then you spend the rest of your career trying to feel that way again — and you probably don’t. I wish I wouldn’t have taken it for granted. In the moment, you kind of think, “Oh well that’s easy, that happens all the time.” It doesn’t happen all the time — that can happen once in your lifetime. You should be able to gold-plate it.

Goldberg: The stratospheric success was all because of the Grammys. I don’t think there’s ever been an album that benefited more from getting Grammys than Nick of Time.

Devine: Nick of Time turned into the little record that could. Almost exactly a year after we released it [April 7, 1990], it became the number one album in America after sweeping the Grammys.

Was: I’m still kind of running on the fumes from that. The month before I did Nick of Time with Bonnie, I had cut “Love Shack” with the B-52s — between those two things, I went from being a pariah to producing Bob Dylan, Neil Diamond, Bob Seger… It changed everything.

And I’m grateful for all that. But if you want the real truth…I’m getting choked up thinking about it. I had done it just to get to know her, and be part of it. I would have done it for free and found another way to earn a living. It was worth doing just to witness that kind of greatness.

Raitt: When the fans come to the show, I want to be able to honor what this album meant to them, and the record afterwards — and it’s the arc, the range of emotions that make those albums and my shows interesting.

Those songs where your heart is broken and you’re longing for someone to call you back, like on “Love Has No Pride” or “I Can’t Make You Love Me,” are as real as “Real Man” or “The Road’s My Middle Name” — all those songs that are brash and saying, “This is what I’m not going to put up with,” and “This is what kind of guy I really want.” The other side of that is that you feel vulnerable, brokenhearted and at your lowest point.

I couldn’t do a whole album of torch songs, just like I couldn’t do a whole album of rock and roll songs. It wouldn’t be showing the whole picture.

© Paul Natkin /Getty Images

To the Editor:

I loved reading Natalie Weiner’s oral history about Bonnie Raitt’s Nick of Time album, and am very flattered to have been included, but I’d like to add something. I recognize that space limitations preclude a complete transcript of conversations, or the mention of everyone who was involved, but there are two people who played a major role on the business side who I’d like to make sure are acknowledged. One is Ron Stone, who co-managed Bonnie with me. Ron and I worked together every step of the way and sat next to each other on that memorable Grammy night. The other is Joe Smith, who was the person at Capitol Records that actually made the commitment to sign Bonnie after his counterparts at other major labels had passed.

Sincerely Yours,

Danny Goldberg

Source: © Copyright Billboard

Please rate this article

- Ed Cherney, Grammy-Winning Engineer for Bonnie Raitt & The Rolling Stones, Dies at 69

- Bonnie Raitt on Channeling the ‘Dark Stuff’ For Her New Album and Why She Likes That Bernie Sanders Is Putting Hillary Clinton’s ‘Feet to the Fire’

- Bonnie Raitt Picks Her 10 Favorite Duets

- Bonnie Raitt to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award From Recording Academy

- 30 Years of ‘Nick of Time’: How Bonnie Raitt’s ‘Underdog Record’ Swept the Grammys & Saved Her Career

- Bonnie Raitt Video Q&A: ‘Slipstream,’ Feminism, Katy Perry, Plans

- Bonnie Raitt Talks About ‘Dig In Deep,’ Life on the Road, Hijacked Elections and the ‘Wrenching Awareness’ of Wisdom With Age

- Legendary Label Executive Joe Smith Dies at 91; Bonnie Raitt and Garth Brooks Remember His Legacy

Visitors Today : 37

Visitors Today : 37 Now Online : 3

Now Online : 3