It is Alice Doesn’t Day, October 29th, a day to show the system how much it depends on women. Women are urged by the National Organization for Women to refuse to work, in or out of the house, in or out of bed.

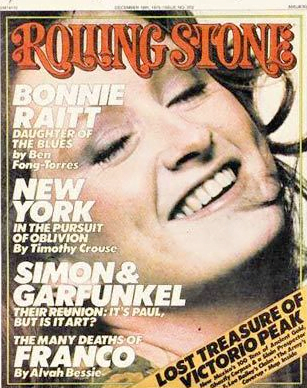

It’s 1:30 on Alice Doesn’t Day, but Bonnie Raitt is hung over and doesn’t know what day it is — she is in downtown Nashville, using Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge as a backdrop for a photo session. As she wanders past a few stores, past a few Nashville cats striding by with their guitars in grip, something, or someone, is bothering her. In a minute she’s back at Tootsie’s. A few steps behind are two urgent-looking young men. She looks annoyed. “This jerk” — she motions to the bearded one behind her — “comes up and starts telling me, ‘I was in jail and I let Jesus Christ come into my life, and he forgave me all my sins.’ He wouldn’t stop. If I was a minister the guy wouldn’t have let up enough to let me tell him.”

The two young men are back, hovering. They do not recognize Bonnie, who will be headlining this evening at the new Grand Ole Opry. They just want her to show up at a revival meeting that night. Bonnie stops posing, nods an irritated head toward the two. “I don’t want these turkeys behind me,” she tells the photographer. The two men hear and seem puzzled, but move off toward a parking meter. Bonnie shoots a glare: “Would you please not watch? I’m already self-conscious as it is.”

She has given them a perfect opening and one of the JC freaks — the one who was forgiven — takes advantage of it: “Jesus,” he soothes, “will free your soul.”

Raitt squints, rolls her eyes. “Jesus Christ,” she mutters, “this town is out to lunch.”

Just past three on Alice Doesn’t Day, she returns to the Spence Manor Motor Hotel just in time to climb aboard the tour bus (called Kahoutek I and featuring chrome mag wheels) to go to the Grand Ole Opry for the sound check. For Nashville, John Prine has been added to the Raitt/Tom Waits bill, and Prine looks like he got good and warmed up the night before. Electric hair, Manchurian moustache, undersized denim outfit, green socks, black tennies. He is tossing a drink around. Tom Waits, as always, is hunched over, outfitted in grimy newsboy cap, slop-dash black suit, soiled white shirt, thin tie and thinner cigarette.

“…and I think I got married to the bartender”…Bonnie is talking…”That’s what happens when you don’t get served your dinner till eleven. I only wanted one screwdriver and I wind up drinking eight of them.” She and Waits and Prine had jammed till 5 a.m. the night before and an entire party had collapsed in her suite. She turns to Tim Bernett, her road manager. “Did you leave that cherry in my bed?” Prine fingers his maraschino and delivers the obvious punch line: “I’ve never left a cherry in bed.”

At the four o’clock sound check, Bonnie falls into another funk. The piano tuner is tuning late, stalling the check for an hour. She strums at her Gibson and recalls her first guitar lessons — self-taught — off Mississippi John Hurt’s “Candy Man” from the Blues at Newport, 1963 album. “It took me two weeks to learn that song,” she says, and proceeds to pick up a new chord — a James Brown-styled C Ninth — from guitarist Will McFarlane.

Sound checks usually give Bonnie and her band a chance to goof off — they invariably get into “Sunshine of Your Love” or “Purple Haze”; McFarlane will throw his guitar over his head and bite out riffs with his teeth. But today, on the spur of the moment, she bows her head and sings a tentative but sweet “Louise,” a Paul Seibel song that is not part of her repertoire.

After a perfunctory performance of “Walk out the Front Door” from the new album, Prine and Waits saunter onstage to run through “High Blood Pressure,” the Huey “Piano” Smith song. Prine, who regularly performed the song until he dropped his backup band recently (“I ran outta money,” he shrugs), takes a vocal solo, giving the good-time tune a soft, furry, Dylanesque whine. Raitt mock-scolds him: “It sounds fruity. Let’s get down — be soulful!”

To illustrate the lyrics of the song, she pretends to be taking a blood pressure reading for Waits, who tends to stagger around near his mike in a cloud of his own cigarette smoke. She tries a guitar chord, but it doesn’t work; Waits himself protests that it looks like she’s tying him up for a fix. Bonnie ends the episode with a crack: “How about if I just wrap his dick around his arm?”

Back on the Kahoutek at six, Raitt resumes moaning. She has a radio interview to be cancelled, dinner to be had, an accountant to be called and a magazine interview scheduled for after the concert. “Ooh, I wish it were tomorrow,” she says. “I just can’t do everything at once.”

Not until 8 p.m. in her dressing room at the Opry House does Bonnie learn that it is Alice Doesn’t Day. A fan has sent her some advice on a sheet of yellow paper bordered by brown postal adhesive tape: “Kiss no ass/Or take no sass/This Alice Does/Get real high off Bonnie’s buzz.”

She wanders toward the stage to watch Prine, who is given to singing and playing with one leg back a ways, on its toes. Bonnie lets out a whoop for him, and he flashes her an illegal smile.

“His face is so cute,” she says. “He’s got no bones, just like me. We’re like the Pillsbury dough twins. It’s like an instant love affair whenever we’re around each other — but he’s married and I have Garry, so I’m glad we don’t see each other that often. But we’re cut from the same stock.”

She cheers lustily at Prine, and after an encore he announces, “Bonnie will be out in a minute” and she screams from the wings: “No I won’t, eat it!” As Prine moves past the curtains, Raitt drops onto her knees and performs falsetto on him: “Oh, Johnny, Johnny, Johnny.” She is on her hands and knees, hops around him and asks to be allowed to kiss his tennies. Prine looks down at her. “Do you have a backstage pass?” he demands.

Onstage, after her opening number (“I Thought I Was a Child”), she casually mentions Alice Doesn’t Day, drawing a few cheers here in “Stand by Your Man” land, and she dedicates the next song, Seibel’s “Any Day Woman,” to the cause:

If you don’t love her, you better let her go

You’ll never fool her, you’re bound to let it show

Love’s so hard to take

When you have to fake

Everything in return…

You just preserve her

When you serve her

A little tenderness…

Bonnie Raitt is a romantic socialist, a politician of the heart. She sings, often using other writers’ words, about the relationship between man and woman — about why the man has always come first; about why that shouldn’t be so automatic — or why it shouldn’t be, period. Like many politicians, she is smart — but erratic. She has causes, all leaning toward activism, but they are clouded with contradictions.

She sings put-’em-up, we-take-no-shit songs to men, but often pines and cries in her songs. She plays brassy blues and bottleneck guitar and never fails to get the audience whooping with her first run down an electric neck, but her audiences seem to love her even more for her interpretations of contemporary ballads.

In Austin, a young girl gasped at the first notes of “Angel from Montgomery,” squeezing her way past a half-dozen pairs of knees to kneel at the apron of the stage. It was as if Joni Mitchell were up there, not Bonnie Raitt singing a John Prine composition.

Bonnie has worked hard to earn what is still, after four years, an…intimate…but growing constituency — and a corresponding power. She wants to use whatever muscle she’s developed to change some of the ways of the business and to funnel money back to community causes and political groups. She frequently does benefits for women’s groups and is organizing concerts for Tom Hayden’s California senatorial campaign.

She doesn’t want the trappings and the traps of success, doesn’t want friends wondering whether she’s “gone Hollywood,” and doesn’t want limousines and jets (her fall tour’s logo depicts a turkey on wheels). But, for political reasons, she needs the muscle that usually comes only with pop-top success. And so she is working on the road and in the studios just about every day.

Bonnie is a natural, earthy woman (though not quite the “lusty, rowdy blues mama” she’s been called). Offstage, she has no prima-donna pretensions, hesitates, even, before asking a roadie to fetch her a drink when she’s strapped down with a guitar and working on a number. Onstage in Arlington, Texas, she shook off countdown nervousness — walking toward the stage, she turned to a friend and remarked: “This is like the last mile and you’re the warden” — and served up some stream-of-consciousness humor. Freebo, her faithful bassist through the years, posited himself behind a tuba for “Give It Up” as Bonnie announced: “Now here’s Freebo on oral martial arts,” teasing him: “A little more practice on that and you’ll be ready for me!” After singing “Sugar Mama” from the new album, she dutifully plugged it: “We had” a lot of fun making it. I always have a lot of fun making it.” Then the voice from her omnipresent third eye: “Oh, she’s so witty — that darn Bon!”

But if she’s having an off day, it’ll show onstage that night. Before her concert in Arlington, she had told a visiting periodista, “Sometimes I feel like a whore. No matter how depressed I am, I go out and I’m okay. It’s kinda like being…phony.” As she approached the wings, she spotted the mountain of sound equipment crates behind the curtains and turned wistful: “Gee, I remember when it was just Freebo and me.” And onstage, she revealed herself before a half-empty house of 1500, emphasizing the downer ballads and closing with a song she had dropped after last year’s tour, “Love Has No Pride.” Heading back to the hotel, she said she brushed aside requests for blues numbers because “they hadn’t earned going back to the blues. It was like one or two people trying to show other people they knew about the blues.” At 3 a.m., with the bars long closed and a need still burning to somehow…party, she and manager Dick Waterman and the band climbed into the bus, parked on the Ramada Inn lot. And it took a listen to a tape of her Santa Monica concert, a couple weeks before, to bring her up. There had been a hometown warmth in the air, Bonnie and her band responded to it, and they were joined for the encore by a parade of friends led by Joni Mitchell, Jackson Browne and J. D. Souther. On the bus, Bonnie slammed the table in delight, poked at Waterman’s arm. “This was like the best show of my life,” she said.

Bonnie Raitt is aware of her occasional verbal excesses, but she admitted, “I don’t think before I talk. In terms of true freedom, you should just be able to be what you are. And that just naturally comes out of my mouth. Me and my brothers’ friends were always a group — I was the only girl and I probably started to make off-color jokes as a way to get in with the guys. And ever since I can remember, it’s been me and a bunch of guys.

“I really like cracking up with my friends and fool in’ around with the guys,” she said. “It’s a release of tension. But I have to learn how to curb it because, if I am gonna be a model, I should be a model.”

Bonnie was born 26 years ago — she celebrated her birthday November 8th — in Burbank, California, daughter of John and Marge Raitt. You, or perhaps your folks, remember John as the star of Carousel, Oklahoma! and Pajama Game on Broadway, and on “original cast” albums. The two met at the University of Redlands in California: Marge was the leading lady in an alumni production of The Vagabond King, John was the returning hero.

Bonnie spent most of her first years in New York, where her father was doing Pajama Game. The family moved back to Los Angeles in 1957 when Raitt starred in the movie of that play. “He wasn’t around enough to be a real father,” said Bonnie. “He’d come home off the road and bring us presents, so naturally as a little girl I’d fall in love with him. My mother got a raw deal that way, because she was strict and had to be both the mother and father. I didn’t get along with her at all. She’s real strong, and I think there was a natural jealousy.”

John Raitt always sang around the house, and Marge was his accompanist on piano. “And we would go to his shows. There was just lots of music in the house. And all three of the kids — I have two brothers — we all sang. I was singing from the time I was two or three. It wasn’t any deliberate, ‘Okay, I’m going to teach you how to be musical.’ There was no force-feeding.”

At age eight, her parents and grandparents chipped in to get her a $25 Stella guitar for Christmas, each party wrapping half of the box. Bonnie’s grandfather was “real musical, too,” she said. “He’s a Methodist missionary and was head of the Prohibition party for 20 years in California. He wrote about 600 hymns and he used to play Hawaiian slide guitar on his lap and play zither and accordion and a piano.” She took piano lessons for five years. Her teacher, she remembered, told her she had “a quick ear.”

“By the time I was ten, I taught myself how to play my grandfather’s slide guitar. When I was 11, I got enough money to get one of those red Guild gut-string guitars.”

The only daughter of a famous Broadway leading man had to scrounge for money to buy a guitar? “My parents were Quakers and Scottish,” she explained. “They were both raised real poor, and we got a minimal allowance. We had to earn if we wanted anything. I’d iron clothes if I needed to make extra money.”

John Raitt was an isolationist from the Hollywood showbiz circuit. Off the road, he liked to stay at their home atop Mulholland Drive in Coldwater Canyon, working in the garden and fixing up the house. His antistyle deeply affected Bonnie.

“I wasn’t allowed to hang out, because I was always the first kid on the bus or the last kid off. It took me an hour to get to school every day. And by the time I’d get home it’d be four, and for me to get back down the hill to play with my friends, I’d have to get somebody to drive me, and my parents weren’t into it. That’s how I got into just sitting in my room playing a guitar.” And worrying about her freckles. “I had a dream once where people were segregated — the spotty from the clear. And I saw these magazine ads: HIDE UGLY FRECKLES. I used to try and bleach them out with lemon juice and Tide. And then Doris Day came along and changed my life.”

At age eight, in 1958, the year of Perez Prado and Domenico Modugno, of “Sugartime” and “Witch Doctor,” Bonnie was tuned into R&B radio and listening to her older brother’s records of “Rock-in Robin” and “Yakety Yak.” “I didn’t have one of those things for Frankie Avalon,” she said. “I liked my dad. I thought he was hot looking because he had that same kind of hairstyle.

“When I was in junior high, the peer-group pressure was to like Jan and Dean. In the summer everybody would go to the beach and get tanned and learn how to surf. Everybody cut school. And I was redheaded and didn’t get tanned and I lived in the canyon and couldn’t get to the beach.”

In the summers, there was camp in the Adirondacks while John Raitt did Dinah Shore’s summer-replacement TV show. Later, he would do the summer-stock circuit. Altogether, Bonnie was packed off to camp every year from age eight to 15.

“So every summer I’d miss all that romance and the beach. I was the kid that always went away.”

But Bonnie liked the feeling of being somewhat different. “I always looked down on those kids in L.A.,” she said. “If I hadn’t gone away in the summer, I would have become a real cheerleader, L.A. Westwood kind of kid, gone to UCLA and majored in Spanish. That kind of stuff.”

The camp was run by friends of her parents, fellow Quakers, and the counselors were college students from Swarthmore, Antioch and Reed, many of them into the peace movement, Joan Baez and Pete Seeger. Bonnie found herself itching to be older than she was.

“I took to wearing a peace symbol around my neck when I was 11, around 1961. It represented my whole belief! And I used to wear olive green tights and black turtlenecks and I had a pair of earrings — my mother wouldn’t let me pierce my ears, but I had a pair of hoop earrings. I’d grow my hair real long so I looked like a beatnik.”

But Bonnie wasn’t just playing make-believe. “Being a Quaker, Ban the Bomb was a reality since I was six. I mean, at Quaker meetings at Christmas time we’d decorate trees with ornaments and dollar bills. We were getting money for Algerian refugees. And the whole thing was to learn about Christmas in other countries. I was real aware of the Third World getting ripped off, that kind of thing.”

John Raitt was a member of Fellowship of Reconciliation and SANE, and he made films for the American Friends Service Committee. But he and Marge were more Quakers than radicals and they didn’t encourage Bonnie in her pursuit of life as a beatnik-come-lately.

“To do what my dad did, you had to live in a house and drive a Lincoln. I always was very embarrassed when we came to Quaker meetings in a nice car ’cause my parents both look larger than life. They’re both really ridiculously good looking. I wanted my parents to drive a VW and my mother to not set her hair. But she had to. I remember my mother explaining to me that it was very important, especially since my dad wasn’t exactly on the top rung as a major star, to drive a car that made it look like you still were.”

When Bonnie talks about the post-Broadway career of John Raitt, her tone assumes a loving defensiveness, a loyal daughter’s bitterness. And she learned from his mistakes. “I could never let anybody control my life like he did.”

After Raitt’s Broadway run ended in 1956, he traveled with stock companies. “He wasn’t washed up; he made more money off Broadway,” said Bonnie, “but it seemed like the circuit was somehow not as glamorous as Broadway.” Raitt now takes his own troupe around the country, performing Kiss Me Kate, Camelot and the like.

“He does what I do,” said Bonnie, “travels around in buses and does shows. In fact, just the other week we passed each other on a highway and waved to each other. Then, when we got to our hotel, I found out he’d stayed there, and he sent me a message: ‘Don’t eat the fried chicken!’

“I thought he was great,” said Bonnie, “and I watched him not get a show. He didn’t really make mistakes. He just seemed to be at the mercy of his agents. He had to wait for someone to write a show and then be in the show and maybe one reviewer would kill it. And it made me mad that he wasn’t on Broadway and all these punk imitators, Robert Goulet and all….”

John Raitt is currently back on Broadway with a revue called A Musical Jubilee. He saw Bonnie perform at Avery Fisher Hall, then attended a party for her at Sardi’s.

“She watched me struggle for years,” he said. “I’d like to think that she learned something about dignity and integrity.”

In her early teens, Bonnie’s music got folky. “I was like Miss Protest,” she said, “the fat Joan Baez for sure.” At 15, she and a friend named Daphne played at a Troubadour hoot night. “We sang combination Scottish and Israeli songs. We were like a female Joe and Eddie. I thought Joe and Eddie were hot stuff.”

Bonnie went to University High School in Hollywood, also home away from home for a few years to Randy Newman and the kids of numerous stars. Bonnie went steady with one of Jerry Lewis’s sons. A semester before she planned to go to Poughkeepsie, New York, to attend a progressive, Quaker-run high school there, she ran for the position of mascot for the Uni Warriors.

“It was a complete joke,” she said, since she’d never attended a football game and didn’t plan to. “I remember telling the guy I was running against, ‘Listen, it’s in the bag. I’m leaving but don’t tell anybody. I just want to see if I can win.’ “

She ran “because no girl had ever run before,” she said. Also, “You had to run for a student body office to have that on your college application to get into a good college.” She won, went to Poughkeepsie, then chose Radcliffe from among seven universities that accepted her.

“Harvard had a ratio of guys to girls that was four to one…they didn’t have a phys. ed. requirement, and they didn’t make you come in at night.” But she was “serious” academically; she was planning to go into African studies.

“I didn’t want to work in America,” she said. “I thought it was kind of hopeless. I didn’t like growing up wealthy and watching all this waste — too many cars, too many pretty people, too many manicured lawns. I lived in the privileged section of Los Angeles. It’s just ironic about having been raised to understand what’s wrong with this country, to want to work with civil rights and yet live in this fantasy world where there’s barely any black people or barely any discrimination.”

Bonnie was idealistic, she said, until age 16. “Then I just said, ‘Forget it.’ The country was falling apart in the Sixties, it was just a lot of hedonistic rock music. It went from the beautiful days of Selma and SNCC, when white and black people were working together in the South…then Watts blew up and all of a sudden black power came about, and there wasn’t anything pleasant about being a white person working in America.”

At Radcliffe, she played her music at “folk orgies” during exam periods, at hoots and in her own dorm room where she answered her fellow dormies’ requests for songs like “Suzanne.”

Still, she considered herself a blues freak, and in her freshman year she met white blues freak Number One, Dick Waterman.

Dick is a beady-eyed man with a shock of black hair. He is 40 and looks like a 28-year-old man who looks 40-ish. He speaks haltingly in a high voice, is smarter than he sounds and spends most of his office hours on Bonnie. Dick had been in Cambridge since 1962, working as a photojournalist. He covered the 1963 Newport Folk Festival for the National Observer, and in 1964 rediscovered Son House, who was interested in working again but had no manager. Since then, he has managed Fred (“I Do Not Play No Rock & Roll”) McDowell, Skip James, Arthur Crudup, Junior Wells and Buddy Guy. He not only managed them, but housed them, fed them and force-fed dozens of colleges around the country into booking them in blues festival packages.

Dick, then 33, and Bonnie, 18, met at blues hangouts like the Club 47 in Cambridge and WHRB, the Harvard radio station. “We were just sort of vague friends,” said Bonnie. “Then after a while…. I think he liked redheads or something.”

But in 1968, blues were giving way, she said, to “all that psychedelic supermarket stuff. So Dick picked up and said, ‘Forget Cambridge,’ and went to Philadelphia.”

Bonnie herself took the summer of ’68 off to go to Europe with two girlfriends, and in England she discovered the work of Sippie Wallace, a woman who would later be called her “mentor.” Sippie Wallace was 70 and had been making records since the Twenties. She wrote such numbers (now identified with Bonnie) as “You Got to Know How” and “Women Be Wise.” Bonnie heard an album Sippie cut in 1966 while on a European tour with Junior Wells, Roosevelt Sykes and Little Brother Montgomery, among others.

“I’d never heard a voice like that in my entire life,” said Bonnie. “I liked Bessie Smith but I wasn’t a big fan of classic blues, and Sippie was somehow much more raw.”

Sippie, she said, is not so much her mentor as “my sassy grandmother. She probably, in her day, was as sassy as some of the things I get into. There is just no gap.

“And did I tell you she thought I was Karen Carpenter? She wrote Dick a letter: ‘One day I hope to be able to have Bonnie play drums behind me!’ ” Bonnie bounced with laughter on her hotel bed.

Sippie, her career curtailed by a stroke and chronic arthritis, first met Bonnie in 1972, after Bonnie had recorded three of her songs. Sippie joined Bonnie onstage at the Ann Arbor Blues Festival singing in public for the first time since that 1966 tour. Last year she joined Bonnie for concerts in Boston and Washington D.C. She was still confined to a wheelchair and able to play the piano only on her standout number, a low-voiced, trembly, angry-sounding “Amazing Grace.”

On November 1st, Sippie, who lives in Detroit, performed with Bonnie again, in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Her arthritis has regressed and she was back on piano, dueling with Bonnie on several numbers and snarling out a new song: “Bonnie, You’re So Wonderful.” A packed house at old Hill Auditorium capped the four-and-a-half-hour show with a rousing “Happy Birthday” to Sippie. She was 77 that day.

After Bonnie’s return from Europe in 1968, she continued to see Waterman — and friends. “It only cost $8 student standby to fly to Philly,” she said, “so twice a month I’d fly down there. That’s when I started to hang out. I would skip school a lot, we would take off to lots of little blues festivals Dick would book. And I think I went to almost every gig.”

Occasionally Bonnie would pick up her guitar and work out arrangements on blues tunes. “But I mean I had this whole other life. Music at that point had become a hobby. I was mostly a college student. I still was really working at having to study. And it was real hard to try to do my homework with Fred McDowell sitting ten feet away from me.”

“She played well when I met her,” said Dick Waterman in Houston. “She had a real genuine love for the music. There were many people trying to be like Michael Bloomfield or Johnny Hammond,” he said, but Bonnie had the advantage of access — through him — to all the blues performers. She took advantage, he said, to ask them about tunings and songs. She would return favors later by hiring artists as opening acts at her concerts. The musicians’ initial response to her, Dick said, was “sort of amusement. They thought her interest in the blues was some kind of freakish quirk. But she’s proud that Buddy and Muddy and Junior and Wolf now regard her as a genuine peer, not ‘She plays good for a white person or a girl,’ but, ‘She plays good.’ “

Dick turned reflective. “It’s kind of sad for her, on a personal level, that as she became more popular, the men she would’ve helped the most either died or retired. Fred, Skip James, Arthur Crudup died, Mance Lipscomb suffered a stroke and no longer plays, Son House is retired. She had never spoken about Fred’s death of cancer in the summer of 1972 when she was doing her second album [Give It Up] in Woodstock, but it hit her really hard. It was almost as if she was angry that they just didn’t have a little more time — she could have done it for them. As her popularity was climbing and helping them was a real motivation, those men just ran out of days.”

McDowell was scheduled to perform a duet with Bonnie on “Kokomo Blues,” but he died the night before he was to make the trip to Woodstock. Bonnie did the duet herself on her next album (Takin’ My Time). “Well,” said Bonnie, “there’s something awkward about getting so close to old people, you’re just asking for so much heartache. You know they’re gonna die, and you watch them not get appreciated and you know the time’s coming. Fred didn’t know he was dying and we did, so for the last six months of his life it was real hard to deal with him.”

After the show in Austin, Bonnie fretted in her dressing room about the people waiting to see her in an adjoining room. “I’m trying to figure out a way to sneak to the bus,” she said. “I really don’t want to be rude, but I used to always talk till 4 a.m. and spend an hour telling someone why I couldn’t talk to them. I want to get over to Antone’s and pay my…respects.”

She was able to move by the 30 visitors in a breeze and rode through the rain to Antone’s, a blues club where Muddy Waters was appearing. She snaked through the crowd, up the stairs behind the stage and found Muddy on a sofa with a local ragtime pianist, Robert Shaw. “I just came to say hello,” she began, and Muddy stormed back: “Don’t you never say goodbye!”

She has known Muddy since she was 19. “He used to sing this song at me:

Only 19 years old

Got ways like a baby child

Ain’t nothing I can do to please her

You keep that young woman satisfied.

Muddy, looking robust — he broke his hip in an auto accident a couple of years ago — told Bonnie: “Austin is the next empire for the blues!” They talked about blues, about depression and sad songs. Muddy lost his wife last year and moved out of Chicago. Bonnie expressed condolences and added a brighter note. “I used to be sad,” she said, “but now I’m happy.”

Still upstairs, she peeked through some drapes to watch Muddy turn the club into a dance floor and get collared into a conversation by Doug Sahm, Austin’s one-man, one-speed (high) Chamber of Commerce. He helped her miss her cue to join Muddy Waters onstage. She would grumble about it for hours.

Bonnie took off her second semester sophomore year. “It was getting silly. I really wanted to be with Dick more than I wanted to go to school.” In Philadelphia she got a part-time job as a transcriptionist with the Quaker group, the American Friends Service Committee.

As for performing, it took a listen to another singer to inspire her. “It was at the Second Fret in Philadelphia and she was singing stuff that seemed kind of dated. And I said, ‘If she can get away with singing those songs, which are basically not very original…I do the same thing…’ And I was just sick of typing. I wanted to quit my job and I didn’t have any money — I mean, my parents never supported me — so I auditioned.” She and Dick knew the owners, which didn’t hurt her chances, and she was hired to open for a local band, Sweet Stavin’ Chain, for ten percent of the door. She made $54 and was hired back for her own four-night stand.

“I sang ‘Built for Comfort, Not for Speed,’ ‘Bluebird,’ ‘That Song about the Midway’…James Taylor songs…God, I did…boy, some Elton John…and ‘Walking Blues,’ ‘Women Be Wise’…all the songs on my first album.”

Bonnie finished her sophomore year and a semester of junior, then found work in Worcester and Boston. She thought she sang “fruity” but, she said, she was playing “badass guitar.”

With help from Dick, she got a job opening for John Hammond, one of her first idols. “I liked his neck off his first album cover,” she said, craning her own neck to imitate the album shot. “I mean, he was my first Fabian. So when I had first started to play and it was still kind of cute and ‘Ha ha, Bonnie’s playing to make some money,’ as a present, Dick got me a gig at the Main Point and said it was with John Hammond. It was for $200 for the four nights, and I was in the middle of my set when he walked in with a leather coat on with the collar up — like with the points sticking up. With his hair all greased back. Holding this guitar. And then he sat and watched. I think I was the closest to…I came for the entire set, in whatever spiritual way you do that.”

They later became friends — “just friends” — but at first, Bonnie was almost speechless. “I mean, what do you do when you meet someone that you’re not only sexually completely excited over, but he represents everything you’ve ever wanted in anybody. I mean, I had been listening to him on records since I was 13, that Blues at Newport, 1963 record. If there was a teeny little picture of John Hammond on the back of that album, that was enough. God, I just went crazy.”

Bonnie worked her first few jobs by herself. At the Second Fret, she had met members of a local band, the Edison Electric Band, and when they broke up, Raitt hired their bass player. “I was making $300 a night by then, so I could afford it,” she said.

“It” is a former champion tuba player from the West Pennsylvania State Marching Band, a football player there “until the mid-Sixties when everybody found marijuana and got weird.” This particular person proceeded to grow a healthy head’s hair, adopt the name “Freebo” and join Bonnie Raitt. For two-and-a-half years, it was just Bonnie, Freebo and Bonnie’s dog, Prune, driving from gig to gig in a VW. “I never even had an apartment,” Freebo said.

“We’d stay in dorms at whatever college we were playing, or share hotel rooms,” said Bonnie. “It was real hand-to-mouth.

“Onstage we sat next to each other with a little Matthews Freedom Amp, which runs on 40 flashlight batteries or you can plug it in.” Raitt played a steel-bodied National guitar in a “kind of style that covers both rhythm and lead parts, and Freebo would fill in second guitar parts on the bass, ’cause his head is just lyrical that way.”

In the spring of 1971, Bonnie signed with Warner Bros., the label she wanted most to be with because of her respect for such artists as James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Ry Cooder and Randy Newman. Dick worked out a contract giving her a good deal of artistic control, and she did her first album at a camp on Lake Minnetonka, west of Minneapolis.

From the beginning, she was thinking politically.

“I was very uncomfortable going with a big company and I thought it was immoral, politically, to be a leftist, to be trying to be a star…” But club owners had told her that they could use the advertising help a record company could provide.

Recording in a four-track studio garage in Minnesota was a way for her to use corporate money to help a friend, Dave Ray, get a recording scene going, and it was true to her nature. Recently, she said, “I met Ringo at a Clive Davis party, and he said, ‘I like your stuff. You should go back to the garage.’ “

But working with friends and neighbors — in Minnesota, in Woodstock and even in L.A., where she moved in 1973 and where her social circle had encompassed Lowell George and other members of Little Feat — was difficult.

Takin’ My Time, she said, was essentially recorded twice — once with Lowell producing — “We were too personally involved to get along” — and then with John Hall of Orleans. The cost of that album put her in a vulnerable position with Warner Bros. She was left with only $10,000 for her next one, and Warner told her they would advance her additional money only if she would hire a producer with a proven (hit) record.

After a long search, she hired R&B veteran Jerry Ragovoy, and for the first time she found herself in a real studio situation, with session people she didn’t know. Her guitar was left unused; she and Ragovoy had tiffs over song selections — he thought she was in a blues rut — and she wound up ambivalent about the album. “It’s a pretty record,” she said. “It was too slick, but I learned a lot. I learned that I really needed a producer.”

And Bonnie’s singing matured. What sometimes sounded, in 1971, like a frantic white girl’s voice trying to sing ancient black music is now a real instrument. Bonnie always had a natural soulfulness and a good feel for the phrasings of blues music. But now she can use her voice to by turns narrate, scold, kid, challenge, wonder, moan, assert herself and, more than ever, rock & roll. The base is as sweet a soprano as ever, but there is a new layer of husk.

Freebo, who’s been on every album, credits Ragovoy. “The environment changed her singing,” he said. “She was in a professional world with Streetlights and had to act like one. She was being told, ‘Come on, Bonnie, be a professional, don’t find excuses from the bottle, don’t cop out with your friends. There you are, you know, get down.’ And she did. The biggest growth is in her confidence in her voice. A lot of it came out in Home Plate.”

For Home Plate, Bonnie hired Paul Rothchild as producer. “It combines all the good things on the first albums, like the group feeling, everybody putting in input [several songwriters ended up arranging or playing on their tracks], a producer taking some of the load off me, providing a structure within which I can be funky, with a band that’s professional, so we got the songs sometimes in three takes instead of 20 because we’d be prepared. And I also think this is the first one where my voice is out, recorded better. It isn’t necessarily true that I’ll never do any old acoustic blues or play guitar, but it represents a time capsule of one particular change that I went through, and I think it’s a change for the better.”

And, since moving to L.A., she has settled down with one man, bought a modest house and broken up her relationship with Jim Beam. “In Cambridge, I had a lot of nights of getting drunk — but not sloppy drunk, and I wouldn’t get hung over. But last year, on tour, the work schedule was so hard and I was drinking, and I started to get hung over in the morning — that comes from being older, not getting exercise and not having good food. And I’d get sloppy onstage. So this year I’ve stopped bourbon, and those nights are few and far between. Onstage I just have wine and club soda.” As for drugs, she shrugged: “Nothing much, a toot ‘n’ a toke.”

In Austin, she declined a toke offered by one of the Beautiful Backstage Women. We were talking about her status as a celebrity-of-sorts and as a model for many women. Sometimes the idolatry is carried to extremes. She recalled an incident at the Main Point.

“There’s only one john in the bathroom there,” she said; “so there was this long line. I went in, everybody’s talking and these women sort of swept me in — ‘By all means!’ — and let me go ahead of them. Then all the conversation died down and, man, I couldn’t pee. It was like the Hoover Dam! I zipped up and left.”

Bonnie is a champion for many women. She sings songs that often speak for them. She pulls her own weight on guitar; she’s the leader of a rock & roll band.

“I get letters from women saying, ‘Your music got me through’ or, ‘You were a real inspiration to me and my music and I really appreciate how strong you are.’ Mostly what I get now is, ‘You make me proud you’re up there, you’re one of the first women that I’m not jealous of,’ instead of saying, ‘I hate you ’cause my old man’s in love with you.’ I get all my response from women, I don’t get any letters from guys. And a lot of gay women write letters — ‘You’re one of my favorites.’ “

Raitt has said before that she wishes gay women — including musician friends of hers — could express themselves fully in their music. If she were gay, she said, she would. “I think I’m the kind of personality that would.”

Despite her ability to double every entendre within earshot, Bonnie is a downright puritan in matters sexual. She is not a fan of rock artists who flaunt their bisexuality; she has never seen a porn film, “and I hate dirty magazines. I really think sex is private.”

Raitt would like to see more women’s songs. “A lot of people say, ‘You don’t do any political songs.’ Well, ‘Any Day Woman’ is real strong; ‘Love Me like a Man’ says, ‘Don’t put yourself above me.’ “

But out of some 300 tapes she’s received — and listened to — each with an average of five songs, she has yet to find a song she can use. “Holly Near is the first woman I’ve seen who was able to integrate political ideas — I mean actual songs about the war and politics — into her songs and not make it boring.” But asked if she might do a Near song, Raitt responded negatively and weakly: “She has red hair, too…and how many redheads can you take?” For now, she will continue to look for “obscure blues people’s songs” and material by her own fab four, Eric Kaz, Joel Zoss, Chris Smither and Jackson Browne. She does not custom order songs, “but they all know I need songs. Eric wrote ‘I’m Blowin’ Away’ for me, I think. After he wrote the first line about, ‘I’ve been romanced, wined and danced/Crazy nights and wild times,’ he called me up and said, ‘I’ve got a song for you.’ “

Bonnie has done her last interview and at 4 a.m., the morning after Alice Doesn’t Day, she’s curious about that commotion from down the hall. We walk into one of two parties, this one with Tom Waits and John Prine at a round table exchanging stories and songs, a handful of other people sitting around tugging on beers.

Waits, in his cigarette-filtered voice, is performing “Putnam County,” and has Prine laughing uncontrollably, clapping his feet together atop the table, with lines not in the recorded version:

“He got more ass than a toilet seat/I was hornier than a dog on a chain with two dicks/I was so horny even the crack of dawn wasn’t safe in my presence,” he serenaded. And as he crooned on, over the giggles, toward the end of the song Bonnie leaned over and whispered: “He sounds like Fred — 800 years old.”

Source: © Copyright Rolling Stone

Please rate this article

- Q&A: Bonnie Raitt

- Bonnie Raitt: The Rolling Stone Interview

- Bonnie Raitt’s New Morning

- MUSICIANS ON MUSICIANS Bonnie Raitt & Brandi Carlile

- Bonnie Raitt Ain’t Gonna be Your Sugar Mama No More

On new album ‘Home Plate,’ she sings a woman’s blues to the victims of a man’s world - Q&A: Bonnie Raitt

- Bonnie Raitt attends the 25th Anniversary Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Concert at MSG – NY

- Bonnie Raitt: Bonnie Raitt

Visitors Today : 100

Visitors Today : 100 Now Online : 1

Now Online : 1