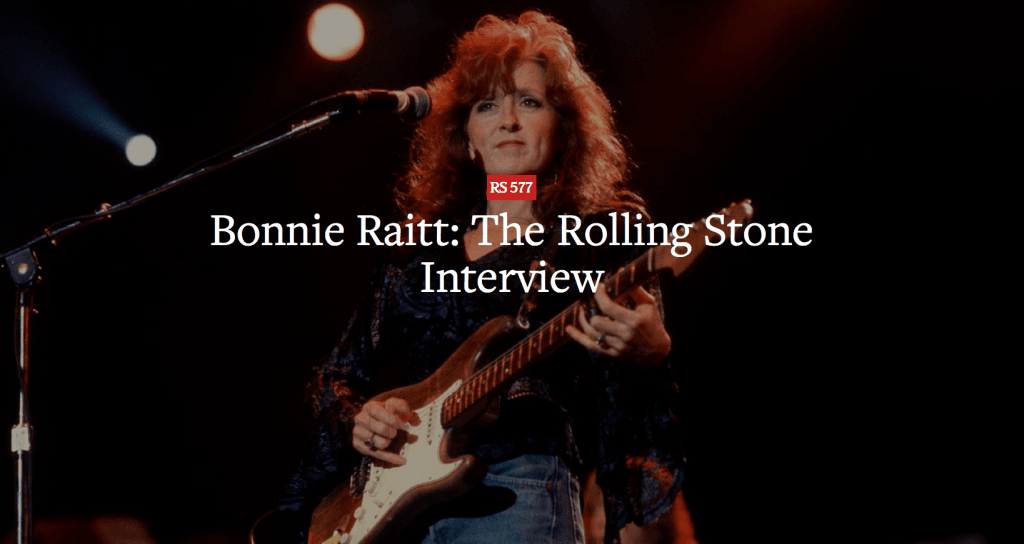

Throughout her career, Bonnie Raitt has gained renown for her dynamic live performances as well as her commitment to addressing social injustices. These efforts have continued during the era of the coronavirus pandemic, even as the disease has taken a personal toll with the passing of her longtime friend John Prine. Shortly after recording a tribute to him, Raitt commends his “deep pathos, acerbic wit and empathetic eye, which he first shared on that masterpiece of a first album—and then he never let up.”

What has the live concert experience meant to you over the course of your career, and how do you think that might change?

One constant that will never go away is the audience connection. I’ve experienced that when I’ve been in the audience. All of us love being there with the people we love. As a performer, I’ve been doing this for 50 years. I also grew up with a father [John Raitt] who played on Broadway and did 25 consecutive years of summer stock and played regional theater until he was in his 70s and 80s. So I really know the power and the joy and the tribal connection that happens when you step on a stage.

I’ve never sold many records. I’m an artist who is standing where I am today because of the live loyalty and excitement and the magic that happened through repeat performances for those audiences. You cannot duplicate it over the internet or even on a record.

I don’t know what’s going to happen, but I’m going to do everything I can to get everybody back into the theaters safely. Maybe it’s multiple nights with the appropriate distance thing. We’ve all been brainstorming about how to do shows in older buildings where the ventilation systems aren’t ideal. One thing I do know is that outdoors is safer than indoors at the moment. So I’m hoping that, by next summer, we’ll have found some venues that we can go back to and different ways for people to feel safe.

What impact has the cancellation and postponement of all these shows had on the people who work behind the scenes?

Independent promoters gave me my start. That’s how I’ve been able to hone my chops and figure out what makes a good show. I learned how to perform and how to hold an audience through live performances in small venues when I was just starting.

This has been devastating to so many clubs and independent promoters and venues that are so crucial to every stage of our careers. The music industry at large— the fans, the journalists, the disc jockeys, the promotion people, the people that help make the clothes, the caterers, the security staff, the ticket takers—has been devastated by the shutdown. We don’t know whether we’re going to be able to recover, but I certainly hope so.

You mentioned that live performance can’t quite be duplicated over the internet. How do you view the role of that medium?

The pandemic has forced us to look for new ways to connect. I watched Jon Cleary’s wonderful Quarantini Happy Hour, replacing his two solo gigs in New Orleans every week with Facebook concerts. Ivan Neville is doing the same and I know there are lots of others. They take real-time questions, which is great, and real-time requests, which is something you can’t really do onstage. So the internet has its own charming way of blasting open things that wouldn’t have been possible in a live concert as easily. So it does have its good side, even if that can’t replace what all of us get from the live experience.

Throughout your career, you’ve brought attention to certain artists in need who have inspired you. While organizations like MusiCares and the Jazz Foundation of America have established COVID-19 relief funds, do you think this crisis might eventually spark a conversation about additional government support, akin to what happened during the New Deal with the Federal Art Project or the Federal Music Project?

I always tried to bring my influences out on the stage with me as much as I could. I opened for Sippie Wallace, Mississippi Fred McDowell and a lot of the different blues acts. Then, when my career circumstances changed a little bit, I said to people like Muddy Waters: “Instead of me opening for you, come and play the college circuit with me and you’ll develop a new audience.” We also tried really hard to get health insurance programs for the musicians because a lot of them were in poor health because they were overworked by unscrupulous booking agents, who had them play six or seven nights a week, three sets a night. And the agent still took 40 percent. When Atlantic had its big 40th anniversary celebration at Madison Square Garden, I found out from Howell Begle that Laverne Baker, Ruth Brown, Charles Brown and most of the people in my record collection hadn’t received royalties. That’s partially because U.S. radio, unlike the rest of the world, doesn’t pay performance royalties, only songwriting royalties. And when it came to record sales, the labels gave a 1-2 percent royalty rate up until 1970 and overcharged them for the costs of recording. To me, it was really important to be able to get financial remuneration for all these artists because we owed them so much.

I would love to see art and music and theater and dance supported by the government. The National Endowment for the Arts has been slashed, although there’s still some support. However, I think in terms of saving the cultural institutions in this country, it’s probably going to take an effort from the nonprofit world. That’s how museums, ballets and symphonies are funded. We have to do the same thing for rock-and-roll and roots music.

Artists have always sung about hypocrisy, satirized those at the top, called out what’s wrong and lifted people up for what’s right. That’s never going to change. The things that I cared about in the ‘60s and ‘70s are not a pipe dream. They’re inevitable and we’re going to keep working for them. I hope that we can still get back to the clubs and that people will want to hang out and hear live music more than ever when we find a vaccine. That way, we can support the people who are out of work that I mentioned earlier. And let’s also pay people for what they’re contributing—teachers, hospital workers, bus drivers, people that are essential workers. People deserve equal treatment, health insurance and a fair wage. That includes musicians and everybody in the music industry as well. I’m hoping that they’ll be a reckoning. People will wake up and we can figure out how to rewrite the plan.

Visitors Today : 7

Visitors Today : 7 Now Online : 0

Now Online : 0