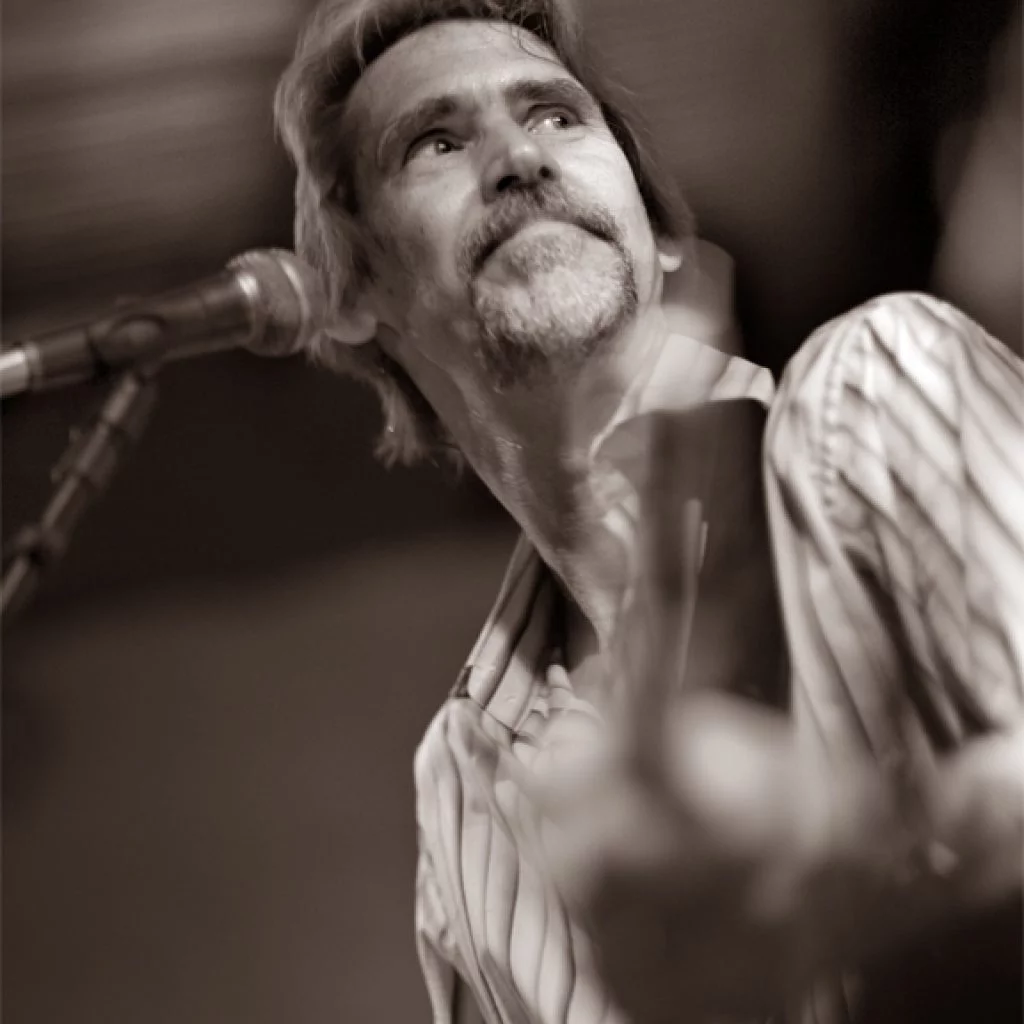

“I Knew,” the third song from Bonnie Raitt’s new album, Dig In Deep, begins with her longtime band punching out a funky groove, but the singer’s slide guitar hovers uncertainly, as if pondering its next move. The red-headed singer’s huge soprano also seems undecided, unsure whether she can keep going in the face of so much loss. “Time ain’t never healed the wound,” she sings with a world-weary sigh, “can’t think of anything that gets any better ‘cause it’s old.”

Time looms large in this new project, not just in the lyrics to the songs but also in the challenge of an artist staking out some new territory that won’t repeat what she’s already done. By the time you turn 66, as Bonnie Raitt did in November, you can’t ignore the past; you have to wrestle with it. “I would have run,” she sings on the chorus of “I Knew,” “but I couldn’t run; I would have lied, but I couldn’t lie, ‘cause I knew.”

She knew that if she wanted to release a 17th studio album, she would have to write and/or find a dozen songs that said something she hadn’t said on the 16 previous projects. She knew that if she wanted to escape the curse of the aging-pop-legend-turned-oldies-act, she had to have songs that could hold their own in her live set. And she felt she had more to communicate. “How cruel is it,” she sings on another song from the new record, “that fate has to find me all alone with something to say?”

“I’ve got a lot of decades of music that I’ve recorded,” she says over the phone from California, “a lot of music that’s been loved by other people, so when I do an album I don’t want to repeat myself; I don’t want to use words that someone else has already used. Otherwise it’s just a retread. So I try to write a song or find a song that says something new. Because if you’re not saying something new, why are you even out here?”

Raitt’s decades of music tell an unusual tale. She started out as a folk-rock-blues singer with a big voice, a slashing slide-guitar sound and knack for reinventing other people’s songs. Her nine albums for Warner Bros. between 1971 and 1986 didn’t sell many copies, but she was a favorite of critics, musicians and roots-music fans.

That all changed in 1989, when Nick Of Time, her first album for Capitol and her first album made sober, won three Grammies, topped the Billboard pop charts and sold more than five million copies. The follow-ups, 1991’s Luck Of The Draw and 1994’s Longing In Their Hearts, also went multi-platinum, charting #2 and #1 respectively and winning additional Grammies.

It proved that you could toil away under the damning label of “a critic’s favorite” for 18 years and then suddenly break through to a much wider audience. But after that best-selling trilogy, it was back to modestly selling records and devoted live audiences.

In this, the 45th year of her recording career, how does Raitt find something new to say? The first verse of “I Knew,” which originally appeared on songwriter Pat McLaughlin’s 2008 Horsefly album, finds Raitt casting off doubt as her voice and guitar commit themselves to moving forward. “Change,” she sings, locking into the beat, “would probably do me good.”

The changes aren’t drastic on Dig In Deep, but they reveal how she’s taking charge of her music. She has often included her own songs on her albums, but this one includes three originals and two co-writes — 42 percent of the songs compared to her previous percentage of 16 percent. This is her second album on her own label, Redwing Records, following Slipstream, and the first that she’s produced by herself — though she’s been credited as a co-producer since 1991’s Luck Of The Draw.

“I’m not a person who gets produced, quote-unquote, by another person,” she argues. “When we’re in the studio discussing the snare-drum sound or the mic placement, I’m right there and involved in the discussion. I’ve been producing as a partner all along. On recent albums I’ve asked a co-producer to join me because I’ve liked the sound of a record they’d done recently. But when I met Ryan [Freeland, her engineer], I knew what direction I wanted to go in and decided I didn’t need a co-producer this time. I’m so comfortable with Ryan and with my band that we know where we’re going without a lot of discussion.”

Four of the five new songs that Raitt wrote or co-wrote are uptempo rockers, from the slippery funk number, “Unintended Consequence Of Love,” which she wrote with New Orleans keyboardist Jon Cleary, to the Stones-like stomper of “The Comin’ Round Is Going Through,” which she co-wrote with her regular guitarist George Marinelli. “There are certain grooves I like to play that I wanted to add to the live show,” she explains, “so I was clear about what I wanted to work on.”

But an awareness of time passing sneaks into even these rambunctious party numbers. The Cleary song finds her addressing a longtime lover and asking whatever happened to the optimistic, enthusiastic people they used to be. “I guess time wore us down,” she sings, “expectations run aground. It’s an unintended consequence of love.”

Another number, “What You’re Doin’ To Me,” is sung by someone who has been worn down by those consequences and has given up on romance altogether. “Just when I thought the coast was finally clear,” she sings in surprise, “you come busting in the door.” The excitement of such an unexpected, late-life love is communicated by a rollicking R&B groove that pits Mike Finnigan’s B-3 organ against Raitt’s piano.

“There’s a style of gospel piano playing that I’ve always liked,” she says, “because it’s a place where honky-tonk, gospel and soul all intersect, whether it’s Leon Russell or Ray Charles. I grew up listening to a lot of black gospel singing on the radio. I don’t play a lot of piano, but that’s a kind of piano I really love.”

Raitt plays a different kind of gospel piano on the album’s final track, “The Ones We Couldn’t Be,” a slow hymn, a post-mortem on a relationship gone bust. She’s “looking through these photographs,” she sings to the other person, “searching for a clue” as to why they were pulled so tightly together and then flung so far apart. This is Raitt at her best, slowly filling her powerful voice with heartbreak. Accompanied only by Patrick Warren’s synthesizer strings, she confesses, “I’m so sorry for the ones we couldn’t be.”

“I still think in terms of a whole album,” she admits, “even though I know people are into downloading individual tracks now. But I’m old-school; I like putting an album together so it tells a story from the beginning to the middle to the end. Finding the right place for a ballad is the hardest, most important decision. That’s why sequencing is so crucial. To me the most important song is the last one.”

To these ears, the album’s linchpin ballad is “Undone,” written by Nashville singer-songwriter Bonnie Bishop. Over Finnigan’s B-3 and ex-Beach Boy drummer Ricky Fataar’s brushes, Raitt eulogizes a shattered romance. “Battle waged and nothing won,” she sings with those big open vowels of hers. “Oh what have I done? The blood has run.

Some things can’t be undone.”

By the time that chorus comes around for the third time, however, she sounds as if she’s singing not merely about a specific relationship but a lifetime of struggles and disappointments — not just her lifetime but anyone’s. The words and music are Bishop’s but Raitt claims them completely as her own.

“That’s just something I do,” she says of interpreting other people’s songs. “I listen to something and by the time it comes out of my head and my guitar, it’s going to sound different. Especially if it’s a song written by a man, there’s going to be changes in keys and in lyrics; it’s going to be reframed in my own style. That’s how I grew up, hearing people like Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald and my father do the same thing.”

Her father was John Raitt, the star of such musicals as Carousel, Oklahoma! and The Pajama Game on Broadway, in movies and on television. He emerged in a time when singer and songwriter were considered two very separate roles in the music-making process. That changed, of course, in the ’60s, not only because songwriters wanted to perform their own works but also because singers wanted to keep the publishing money for themselves.

“Bob Dylan, James Taylor and Carole King ushered in a new era with singers doing their own songs,” Raitt acknowledges, “but there has always been a parallel track where people like me, Aretha, Emmylou and Linda Ronstadt interpret other people’s songs. I grew up singing songs I loved in the backseat of our car, singing my dad’s show tunes, folk-music songs, blues. I came up in an era when people were singing other people’s songs.”

Today interpretive singing seems an endangered art form as every artist and every producer want to control their own publishing, one of the few reliable income streams left in the shrinking music business. What gets lost in this shift is the chemistry of a great singer embodying the work of a great songwriter — of one strong personality encountering another. John Prine, Randy Newman and Chris Smither are superb songwriters, but they have modest voices, and songs such as “Angel From Montgomery,” “Guilty” and “Love Me Like A Man” take on a different life when sung by someone like Raitt.

On the other hand, Raitt is an astonishing singer, but she’s not a prolific writer — and she lacks the rare verbal wit of Prine, Newman and Smither. So she looks for songs like theirs — and he claims that the search for new songs is not all that different from the writing of new songs.

“It’s equally challenging to write a new song or to find a new song,” she claims. “Both can be frustrating. You write and write and you’re not hearing what you want to hear. Or you listen and listen and you’re not hearing what you want to hear. But you keep going till you hear it. You have to come up with new songs or else you’re going to be repeating yourself.”

And what is she listening for from these new songs? In one sense, she’s looking for what she’s always sought: words and music that resonate with the emotional puzzles she’s trying to solve in her own heart. But those puzzles are different in her 66-year-old heart than they were in her 26-year-old heart, so the songs must be different too.

“I can’t separate my growth as a person,” she says, “from my choices of songs over the years. That line, ‘I’d give anything to see you again,’ from ‘Love Has No Pride,’ is something I wouldn’t say now, but there was a time I felt that way — and I still identify with that person. Since I’ve been sober for 30 years, I don’t sing Randy Newman’s ‘Guilty’ the same way, but it’s a useful reminder of the way I was.

“At this point in our lives, with our parents passing and so many friends getting sick, with the condition of the world so terrible, you have to find a way to center yourself so you can withstand the heavy weather, I was a lot more carefree in my 20s and 30s, but that was a different world and I was a different person.”

“Like a heartbeat,” she sings on “All Alone With Something To Say,” “timing is everything. I looked at love when love looked away.” The song is about that familiar experience of realizing what you should have said in a key moment only when that moment is long gone. The song seems to be about a splintered romance, but like so many songs on this album, it could apply equally well to departed parents (Raitt’s mom and dad died in 2004 and 2005) or lost friends. And just because wisdom comes too late for some situations doesn’t lessen its value for all the situations to come.

“To survive that heavy weather,” she says, “you have to try to be good to other people and to be good to yourself — and clean up the messes when you make a mistake. When something’s wrong in your relationships —whether it’s with a lover or at work or in your family — you have to square your shoulders and face it and do something about it. If it doesn’t change in six months, move on, because this isn’t a rehearsal; this is the only life we get.”

Visitors Today : 14

Visitors Today : 14 Now Online : 0

Now Online : 0