by Ann Powers – Dec, 1995

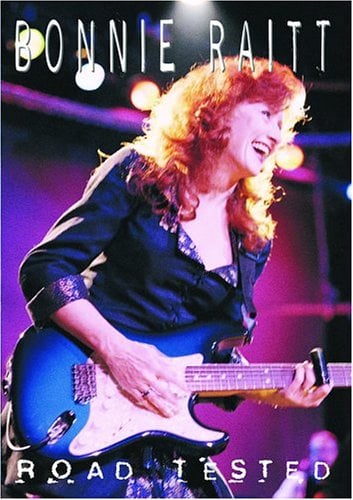

Perhaps it’s her trademark cherry orange mane that makes Bonnie Raitt so open-minded, full of humor and warmth. Redheads understand that their seductiveness is linked to a sense of fun and being a little unusual. But the blues have made her sexy, without turning her into a pinup. Most of all – and this is why Bonnie Raitt has hit her stride in her forties, when most female media creations are taking long sabbaticals at the plastic surgeon’s – the blues value wisdom over callowness, allowing Raitt to act her age and still express more power than she’s ever had before. On her new double live album, Road Tested (Capitol), Raitt sets classic Delta sounds against contemporary hits, proving that no matter what trends overtake the airwaves, some music can always speak to the heart.

ANN POWERS: So Bonnie, you’ve won a million Grammys, had your own ABC After School Special, a guitar model named after you, and now you’re releasing a live album. Is this the last step to becoming a total rock goddess?

BONNIE RAITT: God, I hope not. People usually don’t wait this many years to put out a live album, but it’s a dream come true for me. A two-record set is great because it means I don’t have to compromise my show.

AP: Your first record was done live but in a very different way – at a Minnesota summer camp with some close friends. Do you feel you’ve come full circle?

BR: Well, I don’t imagine that it’ll be the only live record I’ll do. It’s the same as with the last three records. People were asking, “Do you look at them as a trilogy?” And I don’t because what happens when I make the next record? With Nick of Time [1989] I found my own sense of clarity, but I don’t think if it had come out any earlier that anybody would’ve played it.

AP: Your core audience has loved you from the beginning, but in the ’90s there’s been an opening for a woman’s voice, a wise voice.

BR: In the early ’80s it was disco and new wave, and people like Emmylou Harris, Maria Muldaur, and myself just weren’t hip anymore. But in the late ’80s, women like Edie Brickell and Tracy Chapman helped open up the radio. It shouldn’t be age-specific. I really respect artists who continued to work as they got older, like Georgia O’Keeffe, Imogen Cunningham, and Louise Nevelson. In music there’s Etta James, Sippie Wallace, and Aretha Franklin. Mentoring is a great part of the artistic process.

AP: Many people have commented on your adult standpoint, which is now in rock. But the blues have always talked about grown-up lives.

BR: I think speaking about how you’re treated and what you’re longing for, that’s what songs have been about, whether they’re Celtic or African or Gypsy music. The form and the specific words may change, but anger, jealousy, hurt, and loss are all there. True, Neil Sedaka songs aren’t exactly gut-bucket. But that whole argument about “how can a white girl sing the blues? How can you have validity?” Well, I have yet to meet somebody who doesn’t have real pain. And as you get older, those things become richer because experience brings depth. I prefer people in their older, more seasoned form, but I also think it’s thrilling to hear Alanis Morissette and Liz Phair. Those are two of my favorite artists right now. It’ll be great to hear what Liz Phair is singing about when she’s seventy-five.

AP: You do a Talking Heads song [“Burning Down the House”] on this record. How did that come about?

BR: I just love the song so much and I love the Talking Heads, because they were on the funk side of new wave. People who always bought my records will understand why I’m doing “Burning Down the House.”

AP: What do you think of the younger bands in the blues tradition?

BR: I like the Spin Doctors, I think they’re really funky. And I love the fact that the Black Crowes are just such a killer group. They’re inspired by the Faces, one of my favorite bands. These days, it’s hard to hear anybody who doesn’t have some kind of bluesy inflection.

AP: What about your relationships with younger musicians?

BR: My lifestyle doesn’t lend itself to running into people unless they’re in my crew. There are younger performers, like Shawn Colvin, who tell me they’re fans, but I haven’t had a chance to really interact. I’d like to work with Wynonna [Judd]. I think we have the same musical taste, although she’s obviously a little bit more country. But I read a lot of press and I’ve never seen anybody young mention me as somebody significant in their lives. They always mention Chrissic Hynde and Tina Weymouth, and I think, Well, I didn’t make the cut. But that’s O.K. ’cause there really isn’t a young version of me coming up, except for maybe Wynonna.

AP: Let me go back to a different generation. How specifically did you choose Charles and Ruth Brown for Road-Tested?

BR: It was very specific. Ruth Brown’s situation created the Rhythm and Blues Foundation. I found out that R&B performers who recorded before 1970 never participated in the profits from their own record sales. Not Sam and Dave, not Otis Redding. The amount of money they were given was something like one-hundredth of 1 percent. The injustice of it floored me, so I got involved in the inception of the foundation, which was started with a grant from Atlantic Records and Warner Communications, who felt that maybe we could try and get these artists some medical and financial assistance. This is a whole generation that doesn’t have any health insurance. But they don’t just want health, they want gigs, they want an opportunity. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame spends $90 million for a building, but what about the lives of the people who built this music? My absence from the opening was very pointed. It is important to have archives and treat rock ‘n’ roll with respect, but not at the expense of the living musicians.

AP: What’s happened with John Lee Hooker is particularly great. I know you and he shared a Grammy for “I’m in the Mood.” He’s somehow been able to capture the Imagination of many different generations.

BR: He has not diluted any of his raw Mississippi funk. He’s just the same guy that he was back when “I’m in the Mood” sold a million records in 1951. It’s hard to come up with a new and meaningful way to play the blues. The people that can take it lyrically to a different place are the ones that interest me.

AP: There is a particular sensuality in blues music and you’ve always been a very sensual and sexual performer. How have you managed to do it without being exploited?

BR: I would just say that the attractiveness or sensuality that I exude has more to do with the whole person than it has to do with whether my body or face is a certain way. I am a feminist and came up a tomboy with a tough don’t-tell-me-what-to-do stance. One of the reasons I like Aretha Franklin, Ruth Brown, and Sippie Wallace is for their strength. Even though they’re singing about pain, they’re also angry and even playful. That’s why traditional R&B music gets me off. There wouldn’t be any rhythmic music if not for sexuality. Sensuality and sexuality is at once complex and simple. It shouldn’t be cheapened by a girlie show.

AP: Didn’t you nearly collaborate with Prince?

BR: Prince is fantastic! He wears more makeup than I do. Although, compared to Holly Near I look like the most tarted-up babe ever on the stage. In the beginning, I would wear platform boots and tight jeans, and compared to the absolute hardcore feminists I was totally revisionist. I suppose it’s all relative. I loved it when PJ Harvey came out with all that makeup on her latest tour.

AP: What was it like performing with your father [John Raitt] on his new record?

BR: Fantastic! After all these years of thinking I’m a tough blues mama, it was great to realize that I could sing some of these ballads with him. It wasn’t until a few years ago that I put down the need to be so tough and such a rock ‘n’ roller. I think sobriety had a lot to do with it. At some point I grew up enough to say, “Maybe we should do something together,” and I just wanted to share his brilliance with everybody while I had the chance.

AP: You’ve often described yourself as an ordinary woman. But most ordinary women don’t have eight Grammys.

BR: I like to think I’m down-to-earth. It’s the balance between, as Joni Mitchell said, “stoking the star-making machinery” and putting equal time in on my own nurturing. There’s an inside underneath the inside. That’s what my singing is about. Sometimes I’m more true when I’m up onstage than I’m able to be in my regular life. It’s not as exciting to be at home, but I’ve got to learn how to make that work, and then I will be an ordinary woman.

Visitors Today : 27

Visitors Today : 27 Now Online : 0

Now Online : 0