by David Talbot

February 23, 2017

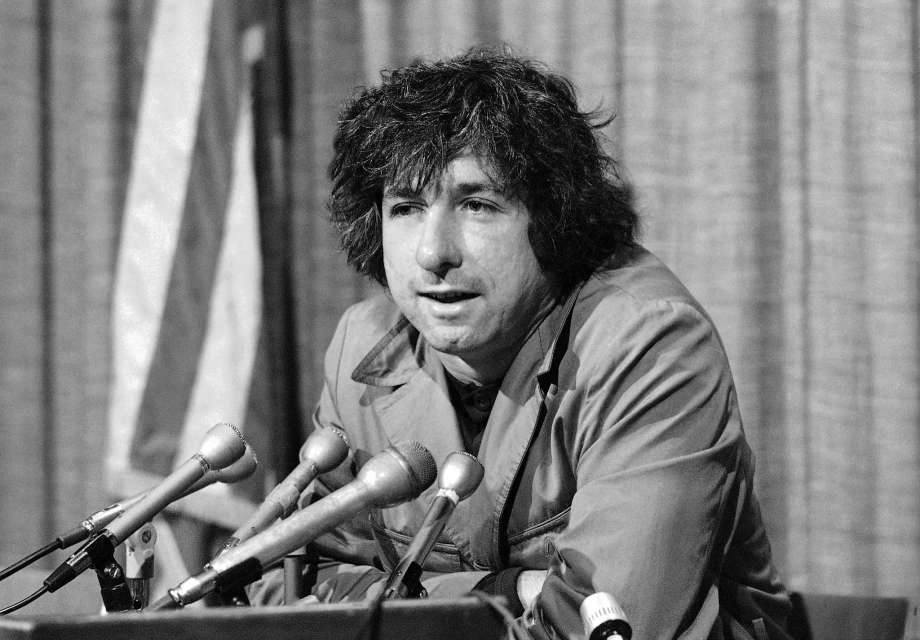

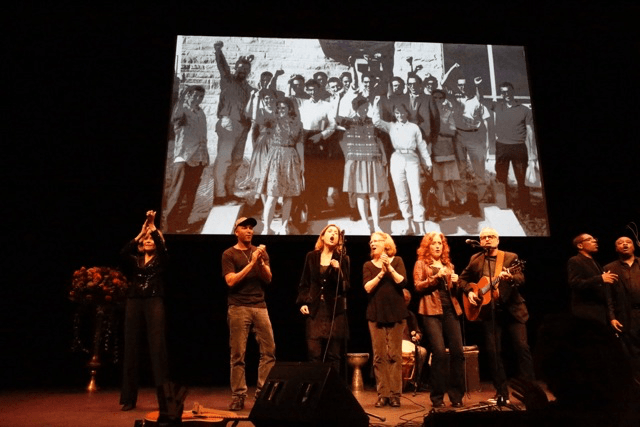

More than 1,000 people crowded into UCLA’s Royce Hall on Sunday to celebrate the life of Tom Hayden, the most prominent leader produced by the New Left of the 1960s. It was a remarkable gathering of a fading but still fiery tribe that included speakers like Jane Fonda, who was married to Hayden in the 1970s and ’80s and worked closely with him for nearly two decades, United Farm Workers legend Dolores Huerta, singer Bonnie Raitt and environmental activist Bobby Kennedy Jr. This was not just a requiem for Hayden, who died in October, but a reckoning for a revolutionary generation that won a breathtaking swirl of cultural and social victories in its youth, only to end up with a fellow Baby Boomer named Donald J. Trump, instead of Bernie Sanders, in the White House.

The Sunday event was not just a nostalgic time machine trip. The family members and friends who organized the event were intent on using the occasion to present an instructive narrative of Hayden’s life filled with relevance for today. The story told by Fonda and others was of a young militant on the margins when she first met him in 1971. When Fonda encountered him on the Vietnam antiwar lecture circuit, Hayden was wearing black rubber sandals made from the tires of downed U.S. warplanes. She urged him to cut his long hair, buy a suit and tailor his political message for mainstream America. Meanwhile “Hanoi Jane” revived her Hollywood career with films that carefully blended entertainment and politics, morphed into a popular fitness icon, and pumped millions of dollars into a progressive organization called the Campaign for Economic Democracy, whose main goal was to elect Hayden to California office.

The moral of the memorial was clear: Pull yourselves together, progressives, and get serious about running for office and governing America. When Hayden decided to abandon protest for politics — aiming unsuccessfully at first for the U.S. Senate in 1976 and then with more luck at the state Legislature — many comrades on the left reacted with scorn. “They thought he had sold out,” Fonda reminded the audience. But to Fonda, Hayden’s shift from radical activism to progressive politics was a sign of his political wisdom.

Sociologist Todd Gitlin, a fellow leader of the Students for a Democratic Society, concurred with Fonda’s assessment of his old friend. “There were few people in the New Left who were as serious as Tom about taking and wielding power,” Gitlin told me at the memorial event. “I’ve always thought the difference between the right and the left is that they believe in power, while we’re ambivalent about it. It’s the difference between the Tea Party and the Occupy movements.”

Not all of the old comrades who attended Hayden’s memorial were happy with the event’s mainstream narrative. To some, Hayden’s glory days were in revolutionary Berkeley during the late ’60s and early ’70s. After the UCLA event, I sat down over Indian food with two veterans of the Red Family commune, which was Hayden’s political and emotional base in those days: journalist Robert Scheer, 80, and his former wife, Anne Weills, a 74-year-old activist lawyer who left Scheer for Hayden. They all lived together in the two-house Red Family complex on Hillegass Avenue and Bateman Street, along with Scheer’s and Weills’ young son, until Hayden was expelled in 1971 for his dominating and manipulative style, which clashed with the increasingly feminist and collectivist politics of the period. Such were the times.

Scheer and Weills, who have remained close friends, had no problem with Hayden’s leap into the electoral arena. In fact, Scheer himself ran a close Democratic primary race for Congress in 1966, with a young Alice Waters as one of his campaign managers. But he and Weills both feel that Hayden sacrificed too many of his core principles when he entered the legislative arena. Weills, who has represented death penalty clients, pointed to how Hayden backed away from his opposition to capital punishment.

“One of the things I loved most about Tom was his risk-taking, his fearlessness about power — his sense that he belonged there,” Weills said. But, she added, Hayden gave up too much to become a power player.

In the end, inserted Scheer, Hayden’s accomplishments in Sacramento were “lackluster,” paling in comparison to legislative masters like former state Sens. John Burton and Sheila Kuehl, and Assembly Speaker Willie Brown.

“What was effective about Tom was his life of protest,” said Scheer, who objected to how the memorial seemed to suggest that Hayden’s militance was nothing more than a youthful phase out of which he needed to grow.

The dinner discussion about Hayden’s legacy grew more complex when Scheer’s current wife, Narda Zacchino, a journalist who covered Hayden’s California political career for the Los Angeles Times, argued that he had little choice about steering a more mainstream path, considering the intense pushback against him from the political and media establishments. According to Zacchino, the Times refused to seriously cover Hayden’s bold challenge to bland corporate Democrat John Tunney in the 1976 Senate race, despite the insurgent’s rising poll numbers. Considering his political isolation in Sacramento, where Republican governors held office during 16 of his 18 years in the Legislature, Hayden’s record in the state capital was respectable, she added, such as voter-approved Proposition 65, spearheaded by Hayden in 1986 to notify the public of the toxic chemicals that permeate our lives.

In the end, Tom Hayden stands as one of the few New Left leaders who enjoyed even modest success in American politics. Part of this was due to the political system’s harsh rejection of former radicals. But, as Hayden himself noted in his memoir, “Reunion,” this was also a “self-imposed failure” by a radical generation that had a “profound distrust of leadership and structure.” When he was kicked out of the Red Family commune, noted Hayden, one member denounced him as a “politician.”

A new generation of activists must learn from stories like Hayden’s and Fonda’s as they sort out their own strategies and philosophies of power. Must progressive movements reject brilliant and charismatic leadership and celebrity glamour in the name of democratic principles? Or is this an inextricable part of a winning political formula? Stay tuned.

Source: © Copyright San Francisco Chronicle

Visitors Today : 92

Visitors Today : 92 Now Online : 0

Now Online : 0