In a short two or three years, Bonnie Raitt has built up a wide reputation as a proficient blues guitarist, a soulful writer and interpreter of contemporary songs, a warm and irrepressible entertainer. She has appeared regularly at the Philadelphia Folk Festival, and she has performed in scores of little clubs around the country. Last summer she was one of the few white musicians to appear in the Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival.

Bonnie and I did this interview last summer after the release of her first album (Bonnie Raitt, Warner Bros. WS 1953); she’s since put out a second album (Give it Up, Warner Bros. BS 2643). During the interview, our conversation constantly returned to two of Bonnie’s main concerns: her deep regard for traditional blues music and for the many great blues musicians she has known, and her intense awareness of the problems and responsibilities incumbent on an increasingly popular and successful musician (the New York Times recently concluded that she could become “the premiere female vocalist of today’s rock ”).

Bonnie is the daughter of Broadway singer John Raitt. As a child she was often backstage (“that’s the most plastic level — Broadway musicals”), and she learned at an early age “that the music business is fucked-up.” Her parents are Quakers, and in the early sixties they sent her to a politically-oriented summer camp in the East — later to an activist Quaker high school — to counteract the stultifying atmosphere of suburban Los Angeles. The camp fostered Bonnie’s love for music and a political consciousness that is still evident in her attitude towards her work.

Bonnie is committed to doing benefits for political causes, and she refuses to turn her bookings over to an agency. She is intent on having some say in the places she plays, the people she plays with, and how much people have to pay to hear her sing. At twenty-two, she projects the image of a strong and determined woman (though the songs she chooses to sing seldom go beyond the traditional stereotypes of women as the victims of love). She is trying not to be consumed or co-opted by the omnivorous American music industry — a very difficult task, I think — and I hope that she’ll succeed.

. . . I mostly got into music at that camp. It was a political camp, and the people would go on marches, and there would always be music. I had started teaching myself to play guitar when I was about ten or eleven, and at camp I got into political music, people like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, that whole community feeling that came out of that music. And then, in ’62 or ‘63, I heard John Hurt and other blues singers on records; and I liked it a lot; and I was drawn to it. So then I started playing blues.

I got very much into country blues. I liked the delta style the best — Robert Johnson, Fred McDowell, Son House, Tommy Johnson. I wasn’t particularly a Charlie Patton or Willie McTell fan, though I like ’em. And I also like Jimmy Reed and Arthur Crudup, that back-beat, real simple modern kind of blues. I didn’t like the classic blues so much, although there’s one woman whose songs I do. Her name’s Sippie Wallace, and she’s really an incredible singer; her voice is a little too funky, a little too nasal to be that straight kind of jazz singing. I always liked her songs, and she also happens to be one of the few of the old-time women blues singers who are still alive.

I met Dick Waterman when I was a freshman in Cambridge, at the time when the Club 47 was still open. Dick manages most of the blues acts, and we’ve been close friends now for years. I travelled around with him and Son House and Fred McDowell1*Fred McDowell, from Rossville, Mississippi, was one of the last great delta bottleneck guitarists. He died in Memphis at the age of 68, on June 3, 1972, not long after this interview took place. Fred McDowell and Bonnie Raitt were good friends and often played guitar and sang together in clubs, concerts, and at festivals. When she performs now, Bonnie will often include, in his memory, a medley of his songs.

An interview with Fred McDowell appears in Sing Out!, Volume 19, Number 2. His albums are available on Arhoolie, Testament, and Capitol, and his songs are included in the Atlantic Southern Folk Heritage series, the Prestige/lnternational Southern Journey series, and the Vanguard Newport Folk Festival recordings. and Robert Pete Williams, Buddy Guy and Jr. Wells, and all the people that he manages, and I became real good friends with all of them. I used to carry the liquor, and I would be the one who would watch them; because, you know, everybody has different levels at which they can drink and still be able to play.

photographs by David Gahr

The blues festivals would always be interesting, because a lot of musicians would come together who normally would never have met; and it would be interesting to see how they would be influenced by each other. Skip James would run into John Hurt, and Fred McDowell would do Arthur Crudup’s songs. But it would also be sad to see guys who normally would have led a really quiet life start drinking more on the road. I’ve been to nearly every blues festival in the last four years, and I’ve watched these kids from the Student Activities Committee come back saying, “Ha, ha, I’m going to buy Son House a bottle.” They might mean well, but a lot of these men are really sick. And I can’t help thinking that as nice as it is that they were rediscovered and got to play and got to be appreciated, they still don’t have any real understanding of what’s happened to them.

Buddy Guy and Jr. Wells, they have no faith in white kids. They know that even if white kids happen to like blues this year, they still would rather see Johnny Winter. They know that Janis Joplin was making a certain amount of money, and that Big Mama Thornton was making maybe a fifth of it; and that’s why Jr. Wells does James Brown songs. Why shouldn’t he do something to insure his popularity with black people? White people have been fickle before, and next year the blues might not be their thing; that’s why a lot of blues singers don’t work anymore, why all those clubs closed down. How do you explain to someone like Robert Pete Williams who was playing the Second Fret, playing that whole club circuit, making quite a bit of money, when all of a sudden the rug is pulled out from under him? Dick, I don’t know how he does it; he books blues packages into schools, pretty much ramming them down people’s throats . . . they’d rather have the Jefferson Airplane.

It’s also true that people would rather see me or John Hammond do blues than see Fred McDowell; it’s ridiculous. Eventually it would be real nice to put some of the older blues people on the bill with me and try to educate people; I think it’s really important. But a lot of those musicians are really old, and a lot of them have died.

It’s interesting that as blues musicians get older, they turn to gospel music. Blues and gospel, to us it’s the same music, the same changes, but to them it’s real different. Son House was into blues, and then he became a preacher for years, and he tells the story of how he just couldn’t keep away from it . . . he kept hearing that music. They really feel that they’ve sinned. And John Hurt used to dedicate one to the Lord, do a gospel song, and then it was all right to do some blues. And as Skip James got older, he only did gospel songs.

The thing that made me sad . . . I guess it was a year ago last November, Howard University did a blues festival, the first black-sponsored blues festival . . . and it made me sick. There was hardly anybody black in the audience. For the first time Mance Lipscomb could have stayed on the campus, done some workshops, had people talk to him. They put him up in the biggest hotel, they had limousines, spent lots of money. There was no contact with any of the students. It was just the typical festival. And by the time black kids get into their own kind of music, get into blues, all those guys’ll be dead.

I really like blues, but the way I sing I don’t sound like Mavis Staples, so I kind of do half and half . . . half blues and half modern kind of songs. I play bottleneck, I’ve always really liked it; and I can play all of Robert Johnson and Fred McDowell’s things. I can play a lot of stuff, but when it comes to singing what I play, there’s a real problem. There are two bottleneck tunings and certain positions for each one, and you can’t change the tuning and play the same guitar part; it wouldn’t sound like the same song. But since there weren’t any women playing guitar back then when that style was developed (except Memphis Minnie, and she didn’t play bottleneck), all the songs are in A or E, or G or D; and with my voice I can only sing a couple of songs like that, so I have to capo up. But the whole thing with the bottleneck is in getting that octave, which is at the bottom of the neck; and if you capo up, you lose that octave. So until somebody makes a guitar with a longer neck, it’s just impossible for me to play and sing a lot of those songs at the same time.

I also can play funkier than I can sing. I would do a lot more bottleneck, but it sounds strange with my voice. I like to play bottleneck, but it’s frustrating; when you accompany yourself, you have to do the rhythm part and the lead part and the bass part all at once, and you can’t really let loose. So every once in a while when I get somebody to play with, it’s really fun . . . we can just let fly.

I started playing in public in ‘69, and it just happened real fast for me. I went back to school and was playing gigs in Worcester and that area while I was in school; and then I played the Main Point in Philadelphia; and then I played the Philadelphia Folk Festival, which was the first big thing I did; and then I played the Gaslight with Fred (McDowell) and got reviewed in the Village Voice . . . that was in 1970 . . . and from there it’s just been incredible. It’s partly because there are no women around who play blues guitar. I have lots of friends in Cambridge, guys that write beautiful songs; they’ve been around for years playing in the same old bars, they’re really fine, they’re as good as James Taylor; but there’s only so much room in the marketplace for guys with a guitar. It’s partly a sexist thing; they’ll stick me on a bill where they wouldn’t stick a guy . . . but also, blues will fit in better on a bill with a rock band. I always get all this, “Oh, you play real good for a girl . . .” I mean it makes me sick; but I understand that one of the reasons that I can work a lot is that there just aren’t that many women around working without a band. Tracy Nelson or Linda Ronstadt don’t play, so they have to take a band with them, so it’s expensive. I’d rather play by myself, though I have a bass player now.

I personally don’t have any ambition to be any big hot stuff. I like to play, I could play second act, or play at Jack’s in Cambridge for the rest of my life. And that’s what I’m trying to do now, to build a base on live appearances, rather than on records. On the other hand, I have a contract from Warner Bros. in which I have complete control; they just give me the money and I give them the tapes. And I do respect Warners for the fact that they’d take an unknown artist like me and give me unlimited artistic control.

My first record was done in a garage. I had heard that Dave Ray was starting a studio in Minneapolis, trying to do it on four tracks, trying to keep down the whole business of studio costs and middlemen in order to eventually put out records for one or two dollars with a complete accounting of how every penny was spent. And he needed something to get him off the ground . . . he needed money of course . . . and someone had to be the guinea pig. Dave had never recorded anything on this scale, none of us had made a record before . . . it was fun. We rented a summer camp, did it in a garage; it’s a real funky record. The sound quality was irrelevant to me; I enjoyed the record; if somebody else can get off on it, that’s fine. My voice was on the same track with the piano and harp, my guitar was on the same track with another guitar and the bass, the horns were out in the driveway, and the drums leaked on everybody’s track . . . we didn’t really care. It’s more important to me that I did it like that, that I had a really good time and brought some fine musicians together.

I would never want to have a hit single . . . although if you happen to do a commercial song and you have a contract with a recording company it’s hard to see how you could prevent it. I feel really sorry for people like Don McLean; if he doesn’t come up with another hit record, he’s going to be considered washed-up. He’s been doing it for years, he’s going to be writing better and better songs all the time, but once your album is on the charts . . . I mean I don’t even want to be in the ball game.

I don’t need much money to live on. I’ve got no aspirations for driving around in a Rolls Royce. I’d rather play in little places that only charge a dollar, be on the bill with people I really like. That’s the only thing that matters to me, that it’s not a rip-off for the people coming in, and that I have a good time. If I had a hit, I wouldn’t be happy; but I think there are some political things that a person in that position can do. If you get to the point where you aren’t ripping anybody off, but you’re really making a lot more money than you need, it’s not like there aren’t a lot of really good things you can do with the money. You can do an incredible amount of benefits . . . but it’s a big responsibility.

I would rather coast for a while, playing a lot of clubs and building up a following. If your whole following is based on records, if you have a lot of airplay and you don’t play live very much and your next record is bad, you’re gone. But if your following is based on consistent, good live performances, coming back to the same little club over and over ‘till you have a group of people who know your songs and really like you, that’s a real friendly kind of thing. I go back to Philadelphia or Boston and people know me . . . they’re almost like friends. And no matter how big the room is, it could be twenty people or five hundred, I know they know what I do; and I know they’ve seen me before, and they like what I do. The album is superfluous to me. If I make a good record and they enjoy it, then that’s fantastic. But I want what I do for a living to be based on live performances, so I can do it for ten years instead of worrying about which record company is going to promote which record.

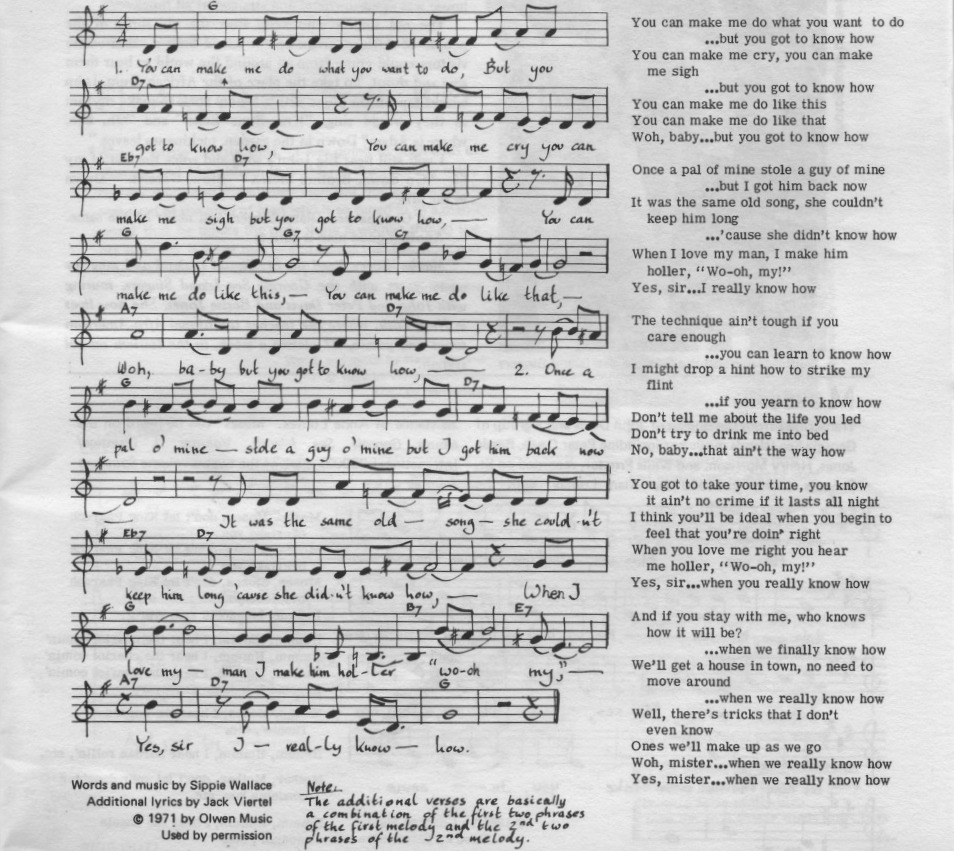

You Got to Know How

The great Texas blueswoman Sippie Wallace wrote this sly admonition a long time before Masters and Johnson published their findings on the subject. Bonnie Raitt first heard her sing it on an album called Sippie Wallace Sings the Blues, recorded in Copenhagen in 1966 for the Danish StoryviIle label. The version Bonnie sings has several additional verses, composed by Jack Viertel. You can hear the song in its entirety on Bonnie’s second album, Give It Up.

Bonnie Raitt and Sippie Wallace appeared together at last summer’s Ann Arbor Blues and Jazz Festival, and a recording of that concert may soon be available from Atlantic Records. Bonnie recorded another of Sippie’s songs, “Mighty Tight Women,” on her first album, Bonnie Raitt; and you can hear Sippie Wallace sing it on the album Spivey’s Blues Parade (LP 1012-available from Spivey Records, 66 Grand Ave., Brooklyn, N.Y. 11205).

cover photograph of Tommy Jarrell and Fred Cockerham by Bill Garbus

SING OUT! Volume 21, No. 6 Nov./Dec. © 1972 by SING OUT! Inc. All rights reserved. Second class postage paid at New York, N.Y. Published bimonthly. Editorial and advertising: 33 W. 60th St., New York, N.Y. 10023. Subscription: 1 year $6.00; 2 years $10.00. Foreign subscription: 50¢ per year additional. Circulation and subscriptions: 595 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10012

Editor: Bob Norman; Music Editor: Ethel Raim; Design and production: Brenda Kamen; Business Manager: Francine Brown; Editorial Advisory Board: John Cohen, Michael Cooney, Barbara Dane, Josh Dunson, Bruce Phillips, Pete Seeger, Jerry Silverman, Happy Traum, Israel Young.

Visitors Today : 31

Visitors Today : 31 Now Online : 1

Now Online : 1