It was a night for the history books at the Bottom Line on April 29, when Afropop Worldwide presented Let Freedom Sing, two sets of music starring The Mahotella Queens, Dorothy Masuka, Thomas Mapfumo, and special guest Bonnie Raitt. The event was part awards ceremony, part fundraiser, part observance of South Africa Freedom Day–the anniversary of that country’s first true election–and all spectacular music. Mapfumo, Masuka, and the Queens were all inducted into the Afropop Hall of Fame. Funds were raised for Afropop Worldwide, Voice of the People (Zimbabwe’s only private radio station), and the families of Zimbabwean musicians who have died of AIDS in recent years. There were serious words spoken about the long path to achieve freedom from apartheid in South Africa, and the ongoing struggle to achieve freedom from newer forms of tyranny in neighboring Zimbabwe. But what most will remember is surely the music that came from one of the most dazzling lineups of southern African musical royalty ever assembled on a New York stage, and from one wild, American redhead with an African soul.

Bonnie Raitt has been a Friend of Afropop since well before she joined the Afropop crew on travels in Mali and Cuba in 2000. By good luck, South African Freedom day (April 27) came just as Raitt was planning to be in the New York area promoting her terrific new album Silver Lining (Capitol). The album has a Zimbabwe connection via its cover of Oliver Mtukudzi’s “Hear Me Lord,” as well as a Mali connection via Raitt’s collaboration with Habib Koite. “Hear Me Lord” has been bringing the house down in Raitt’s recent concerts, so the idea of performing the song as part of this event held a special appeal. But Raitt gave far more than that, co-hosting both shows, and bringing along her band along for a short, cracking set at the end of each.

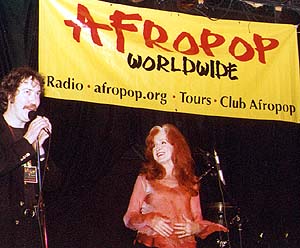

Afropop Worldwide host Georges Collinet, originally scheduled to be Raitt’s onstage foil, was called away to an emergency assignment in Chad, so Executive Producer Sean Barlow stepped up to the plate. Raitt found time to reminisce humorously about tent-life in Timbuktu with Barlow and the Afropop crew. But she also returned often to the themes of the night: celebrating music, and reaching out to people suffering in southern Africa. “Our hearts go out to those in Zimbabwe who are struggling with so much,” said Raitt. “We must let freedom sing, not just tonight, but every day.”

The other business of the night was the inducting of artists into the Afropop Hall of Fame, which honors artists, individuals and organizations who have made extraordinary, contributions to advancing understanding and appreciation of contemporary African music. Prior to Let Freedom Sing, the list was: The Corporation for Public Broadcasting Radio Fund, and its officers Rick Madden and Jeff Ramirez; Bonnie Raitt; Joshua Mailman; The Nathan Cummings Foundation; and the Democratic Republic of Mali. Let Freedom Sing provided Afropop Worldwide with a welcome opportunity to induct the first African musicians to the HOF–because after all, music is what it’s all about!

The Mahotella Queens bustled onto the stage before a nearly full house of patrons sipping donated South African KWV wine and Imoya brandy, and eating food provided by Madiba, New York’s only South African restaurant. The Queens still call their backing band Makgona Tshole, the Jack of All Trades Band, but the members are no longer the gentlemen who first went by that name in 1964, but rather kids who weren’t even born then “This month, I turned 60 years old,” said Mahotella Queen Hilda Tloubatla, in a boast that went down very well with Raitt. Raitt has been telling interviewers all spring that so far her 50s are her best decade yet. Just the same, when Hilda found a moment to propose that Raitt sing a song with the Queens on their next album, the American singer replied that she would need to take heart medication for the session.

Heart is certainly in long supply in the Queens’ act. They still spring and cavort like school girls in joyously synchronized moves. Better still, their voices still come together in one of the richest, fullest, most disarmingly beautiful vocal sounds in pop music anywhere. After a selection of old and new songs, including their gorgeous acapella number “Town Hall,” the Queens invited a surprise guest to the stage.

Dorothy Masuka recorded her first hit–at age 16–in 1951, when the Queens actually were school girls, and Raitt was just a baby. After a storybook life of young musical glory, protest and confrontation with the South African authorities, decades of exile, and a triumphant return to Johannesburg in 1992, Masuka cuts a truly regal presence. To her, the Mahotella Queens are “the girls,” but when she came on stage to join them for two songs, she definitely held her own, both in the cavorting and singing departments.

On Masuka’s song thanking Nelson Mandela, “Madiba,” her rich, jazzy lead was buoyed gloriously by the Queens’ sunny harmonies. Masuka relished the chance to weave among the dancing Mahotella Queens, and the crowd roared, sensing that they were witnessing a first. Masuka’s second song dealt openly with the spread of HIV-AIDS, adding a poignant accent to an otherwise exuberant performance.

After this breathtaking set, South African Consul-General, Nomathamsanqa Xoliswa Ngwevela came to the stage to induct the Mahotella Queens (Hilda Tloubatla, Mildred Mangxola and Nobesuthu Mbadu) and Dorothy Masuka into the Afropop Hall of Fame. Then it was Raitt’s time to shine. With her tight, rocking 5-piece band, she opened with a soulful read of the reggae-tinged “Have a Heart.” By coincidence, Dorothy Masuka had watched a clip of Bonnie Raitt singing as part of the in-flight program on her flight from London. “That woman sings like an African,” Masuka had told me when she realized that they were to perform on the same stage. Raitt then lashed through the ribald, raucous “Gnawing on It,” one of her own compositions on the new Silver Lining. The song’s subject, enjoying sex in one’s advanced years, seemed sweetly appropriate.

More appropriate still was Raitt’s closer, Mtukudzi’s “Hear Me Lord.” With its plaintive, gospel plea for divine guidance, the song seemed to encapsulate the evening’s complex mix of hope, sadness, and celebration. Raitt alternated between channeling Mtukudzi’s crisp, dry vocal delivery and opening up the pipes of her own incomparable instrument to unleash a full-tilt heart cry that brought the house down. Raitt’s bass player, James “Hutch” Hutchinson–a African pop fan for over 20 years now–took the occasion to uncork a popping, polyrhythmic bass solo reminiscent of Bakithi Kumalo’s famous break on Paul Simon’s “You Can Call Me Al.” What Hutchinson didn’t know was that Kumalo was in the audience, and duly impressed. The two bassmen enjoyed a moment of mutual surprise and admiration after the set.

At the close of that first show, Dorothy Masuka and the Mahotella Queens returned to the stage to sing the South African national anthem, “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika.” This time, no costumes or dancing, just one of the most beautiful female vocal ensembles ever, singing what may be the world’s most soulful national anthem. Already, the night felt like a triumph.

The second show turned the spotlight from South Africa to Zimbabwe, with a long, spiritually charged set from Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited. Raitt and Barlow introduced the set putting the spotlight on the two Zimbabwean beneficiaries of the evening, the independent Voice of the People radio station, and a new fund to help pay for the education of AIDS orphans within Zimbawe’s musical community. “It costs just $30.00 to send a child to school in Zimbabwe,” said Barlow. “Well worth it, don’t you think?”

These days, Mapfumo is basing his family and band in Eugene, Oregon, essentially because he doesn’t want his children growing up in the chaos, deprivation, and violence of Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe. Having lost a number of key members of his band to illnesses, including AIDS, in recent years, Mapfumo is well aware of the toll a musicians’ life in Zimbabwe can take. These deaths were in part the inspiration for Afropop Worldwide’s effort to establish the musicians’ family fund.

Mapfumo himself is unquestionably a survivor, and he took the stage that night with seven musicians most of whom are less than half his age. With the exception of Thomas and his brother Lancelot on congas, today’s Blacks Unlimited contains no members who played during the liberation struggle in the 1970s, nor even during the first decade of independence, when the band evolved to include mbiras in the lineup. This particular performance included some very new members, including bass player Sepho “Brighton” Makhaza, and two young horn players from Eugene, David Rhodes on saxophone and Brooks Barnett on trumpet. Guitarist Zivai Guveya, just 20 years old, has grown into his role, channeling the music and energy of legendary predecessors like Jonah Sithole and Joshua Dube. Guveya was joined by yours truly on guitar for two songs, “Disaster,” one of the songs that was banned from Zimbabwean radio in 2000, and “Pidigori,” a traditional song that celebrates the departure of a bad man. Mapfumo never misses the chance to make the Mugabe connection when he introduces this song. “There are some people who, when they go, you just say, ‘Good riddance!'”

Guveya joined Chaka Mhembere on mbira for a fast, hypnotic, traditional jam on the song “Mukadzi Wemukoma” (“The Wife of the Brother”) a song about infidelity and AIDS that has become a touchstone of Mapfumo’s shows over the past five years.

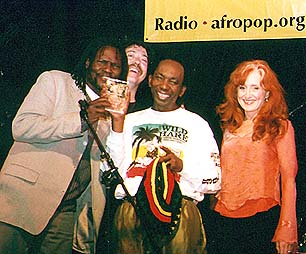

Mapfumo was inducted into the Afropop Hall of Fame by Ish Mafundikwa of Zimbabwe’s brave new private radio station, Voice of the People. VOP airs non-partisan discussions of current affairs as well as varied music programming, including Afropop Worldwide. But in the paranoid environment of Mugabe’s Zimbabwe, where independent voices are feared deeply by the powerful, VOP faces long odds. Having flown from Zimbabwe specifically to be at Let Freedom Sing, Mafundikwa conveyed a deep sense of honor and import in presenting Mapfumo, a cultural icon, with his award. Though Bonnie Raitt stood beside right him, Mapfumo claimed all the star power in the room at that moment.

Then Raitt and her band came back with a cooler set, including a smoldering slow blues, her shuffling 1990s radio hit, “Love Letter,” and of course, “Hear Me Lord,” which once again raised the rafters. Most astounded of all were Mapfumo’s young Zimbabwean musicians hardly able to believe the spectacle of this red-haired fireball singing Mtukudzi, let alone burning into a raucous slide guitar solo. Zimbabwe has very few female pop singers, and certainly none who approach Raitt’s octane level.

Let Freedom Sing did not guarantee a future for Voice of the People. It did not solve the problems of the AIDS orphans in Zimbabwe’s musical community. And it did not rescue Afropop Worldwide from its own financial straits. But it brought together a New York community, and indeed a worldwide community, in a powerful observation of life, history, and the music that binds all of us together. As Raitt told a reporter from allafrica.com, “It is important to support something that lets the rest of the world know where rock ‘n roll, R ‘n B, jazz–where it all started from.” Indeed, the lines that divide musical genres, cultures, countries, and people seemed to grow a little thinner that night.

Source: © Copyright Afropop.org

Visitors Today : 35

Visitors Today : 35 Now Online : 1

Now Online : 1