By ALEX WITCHEL

Published: February 2, 1994

“IS that Bonnie?”

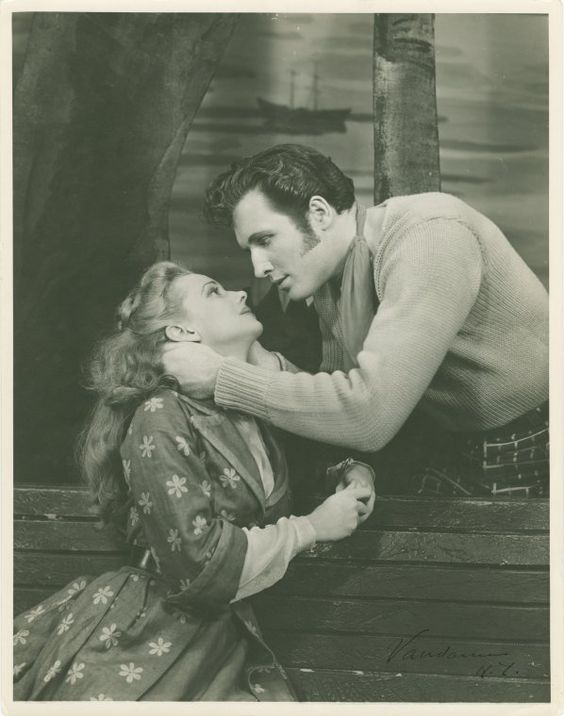

The fan is young, in his mid-20’s, and he looks at Bonnie Raitt, seven-time Grammy winner, as she walks down the street, with love in his eyes and lust in his heart. But who is that with her, that tall, still-dapper white-haired man in the black leather jacket? The fan seems puzzled. It is her father, John Raitt, who was the original Billy Bigelow in “Carousel” on Broadway in 1945 and Sid Sorokin in “The Pajama Game” in 1954, and who last week came to New York to be inducted into the Theater Hall of Fame. By his daughter.

“I’m partial, but I still think he’s the greatest singer the musical theater ever produced,” Ms. Raitt says, in her father’s suite at the Wyndham Hotel. “He makes the character so believable. To be his daughter and watch him kill himself in ‘Carousel’ was very heavy for me. It was hard to separate. What has stood the test of time is his astounding ability to bring emotion to a song, singing from his soul with this incredible, heroic voice.”

“That’s very nice, Bonnie,” Mr. Raitt says, a little choked up.

“Nobody does it the way you do, Dad. Boohoo, I’m never going to get through this speech tonight,” she says, starting to laugh with nerves over the induction ceremonies at the Gershwin Theater, where the Theater Hall of Fame is housed. “People come up to me all the time who saw Dad in ‘Oklahoma!’ or ‘Pajama Game,’ and they say they’ll never forget it.”

Ms. Raitt’s own career path rarely felt as effortless as her father’s. She dropped out of Radcliffe College in the late 1960’s to pursue her music, and later stubbornly refused to compromise her blues-oriented rock to the industry’s more mainstream standards. And in the mid-1980’s she acknowledged and began to treat an alcohol addiction. Growing up with a dad who epitomized the romantic leading man, squeaky clean and always on the side of right, the two seem a classic in opposites.

But, at 44, Ms. Raitt has found that the world has caught up with her music and then some (her album “Nick of Time” sold four million copies in 1990, and her 1992 “Luck of the Draw” sold five million). She is also happily married to the actor Michael O’Keefe. She has come to celebrate her father today and she means it.

Mr. Raitt, who turned 77 on Saturday, is equally proud of his daughter and seems glad that she can appreciate her old man and his music.

“There’s something great about the intimacy of the legitimate theater,” he says. “I’ve played leading man roles for 54 years — never stopped.”

Ms. Raitt says: “Now he does what we call the white hair roles — ‘Zorba,’ ‘Man of La Mancha,’ ‘Shenandoah.’ Wonderful, philosophical roles that say things right to his age.”

Mr. Raitt has continued to play his larger-than-life characters for the last 25 years or so, primarily in summer stock and touring companies, while Broadway has turned host to Vegas-type spectacles with ensemble casts. He always returns to Southern California, where he has lived all his life and where Bonnie grew up.

“Lunt and Fontanne said if you want longevity, stay off both coasts and play where the people are,” he says. He has been true to his word, even playing Tevye in “Fiddler on the Roof” in Ruston, La. Well, that was a stretch, no?

“I wasn’t very good,” he admits.

“I’m sure you sang great,” Ms. Raitt says staunchly. “You did ‘Carousel’ until you were 63.”

Did he ever do ‘The King and I’? He shakes his head.

“The women would have a heart attack if he cut his hair off,” Ms. Raitt says. “My mom packed her suitcase when he cut those curls off for ‘Pajama Game.’ “

“Twenty years ago there were 40 theaters across the country that could afford me,” he says. “Only about 12 are left.” He sighs. “It’s the VCR’s.”

Undaunted, Mr. Raitt still tours a one-man show of his greatest hits and anecdotes, “An Evening With John Raitt,” and this Saturday night he will bring it to the Brooklyn Center for the Performing Arts.

“At his show,” Ms. Raitt says, “I sit in the audience and watch the women’s necks swooning a little and their husbands all say, ‘It’s not his hair, it’s not his teeth,’ and I say, ‘Oh, yes it is.’ Afterward he’ll sit and sign autographs for anyone who wants them. That lack of a stuck-up attitude has always been inspirational. He’s never snobby about taking theater out to the hinterlands.”

But he’s still competitive. Has he seen the Royal National Theater production of “Carousel,” due to open at the Vivian Beaumont in March, starring Michael Hayden, a 30-year-old actor winning raves for his Billy Bigelow? No, Mr. Raitt says, his eyes as flat as his voice. It seems impossible for him to imagine anyone else in the role. And with good reason.

“When I first came to New York to audition for the national tour of ‘Oklahoma!’ Rodgers and Hammerstein were there,” he says. “I asked to warm up first and sang in English from ‘The Barber of Seville.’ Dick and Oscar later said my doing that prompted the writing of ‘Soliloquy’ in Carousel. They said, ‘He may be our boy for the next show.’ “

Ms. Raitt says: “In the 40’s they made Billy Bigelow bigger than life, but now the reality is that he’s a pretty dysfunctional guy. I could see Al Pacino doing him in the film. I’m waiting for Ziggy Marley to play Billy Bigelow, and then I’ll see it.”

The phone rings. “Flowers coming up,” Mr. Raitt says. “Maybe they’re from the Hall of Fame people.”

“They might be from my husband,” she says.

Actually, they’re from Mary Martin.

“Your star shines bright on this historic day,” the note begins before going on to send love from the actress, who performed a famous television special of “Annie Get Your Gun” with Mr. Raitt in 1957 — and from Gene Kilgore, her secretary. Mr. Raitt doesn’t find it at all remarkable that a woman who died in 1991 has just sent him flowers.

“In my show, I always pay tribute to her,” he says. “An audience couldn’t possibly love her as much as she loved them.”

He points at his daughter. “You know, she got a lovely review from the critic in Boston when we did ‘An Evening at the Pops,’ ” he says, referring to a 1992 concert that was broadcast on PBS. Included in the program were their duets of Ms. Raitt’s “Blowing Away,” and “Hey There” from “The Pajama Game.”

“That man said she could be the next Mary Martin if she wanted to,” Mr. Raitt says.

Ms. Raitt smiles. Clearly, she doesn’t.

“I was always drawn to the blues,” she says. “Alberta Hunter at the Cookery was a life-changing experience. I only wanted to get enriched as a performer as I got older, to have an audience which got older, too, and would come to see me when I’m 80. And I didn’t have a legit trained voice. My love was Bob Dylan. But,” she concedes to her father, “as I got older I realized a good ballad was a good ballad.”

He is considerate in turn. “On the 50th anniversary of ‘Oklahoma!’ last spring I sang the title song on the stage of the St. James before a preview of ‘Tommy.’ I said, ‘Most of you people know me as Bonnie’s father.’ “

Rosemary Raitt comes in from the bedroom. She and Mr. Raitt were college sweethearts but didn’t marry then because she was Catholic and Mr. Raitt was Presbyterian (he later became a Quaker, and a conscientious objector during World War II). He first married Marjorie Haydock, with whom he had Bonnie; her older brother, Steven, who is a sound technician and designer, and her younger brother, David, a musician and builder of yurts, which are Mongolian round houses. After the couple divorced he married Kathleen Landry, and when they divorced, 14 years ago, Mr. Raitt heard from a close friend in his hometown of Santa Ana, Calif., that Rosemary had been widowed.

“Having played Zorba, I believe in grabbing at life,” Mr. Raitt says. “So I called and this lovely voice answered. ‘I’m free now,’ I told her, ‘and coming to dinner.’ First she had the typical woman’s response, that her hair was in curlers. And I said, ‘How long will it take you to get ready?’ And she said 45 minutes. Then I got nervous because the last time she had seen me I was a dark, curly-headed guy.

She was nervous, too, and she said to me, ‘What do you see?’ And I said, ‘The same eyes.’ About two weeks later I brought my suitcases and said ‘I’m spending the rest of my life with you.’ So in 1981 we were married, 41 years later. Bonnie sang one of her songs at our wedding.”

“It was ‘Safe In Your Arms,’ ” Ms. Raitt recalls. “I could hardly get it out.”

He returned the favor by singing “My Heart’s Darling” from the Broadway show “Three Wishes for Jamie” at her wedding in 1991. The memory prompts him to sing a verse right now.

“It stopped the show opening night,” he claims.

“It stopped the wedding, Dad,” she counters.

The first time Ms. Raitt saw her father on stage she was 5 years old. “It was ‘Pajama Game’ on Broadway and I remember being backstage with you and Eddie Foy putting on makeup and running around in your underwear,” she says.

As she speaks, he says, “I never had my kids backstage.”

They laugh. Certainly, after all these years their differences are apparent. But how are they similar?

They both look blank. “Well,” Ms. Raitt finally says, “I think we have the same dedication when it comes to our talent.” He nods. “I don’t want to get another job and neither do you,” she says. “We’ll do anything to keep this gig.”

Of the 1,060 performances of “The Pajama Game” Mr. Raitt played on Broadway, he missed only one, because of laryngitis. Ms. Raitt says that in 22 years she has missed only two shows. “On stage the adrenaline suppresses the illness and you can sing yourself well,” she says. “I’ve got good genes.”

And what was the downside of having a leading-man father who looked so perfect and always did the right thing?

“It was hard to let him be a human being,” she says without hesitation, “and he’d be gone on tour for weeks.” She looks at him, and though his face doesn’t change, in that moment they seem to mutually agree to drop the downside, pronto.

“He was always so athletic, handsome, youthful,” she goes on lightly, “not the stern dad type. He was hipper than other dads, with sideburns, all buff. And we had really cool cars.”

So, on this day of reflection, does he have any regrets?

“No,” he says. “I always held out for quality shows. I am most proud of what I maintained in my career, bringing theater to the people who can’t usually get to see it, without insulting their intelligence.”

“He never sold out for a quick buck,” Ms. Raitt says. “If he did Vegas he would have been a bigger star, but he didn’t want to sing for drunks and hecklers, and neither do I. To this day I’d rather play small college audiences than big clubs. I always thought there was something really cool about being the underdog and playing just for the people who want to hear it. To have a nice moderate career for a long time versus a big, splashy one for a short time. I was always angry that people weren’t writing shows for my dad. But by the 70’s, that leading man type of hero wasn’t in vogue to write shows around.”

Later that night, at the Hall of Fame induction that honored the era when those shows were written, Ms. Raitt spoke eloquently. After Mr. Raitt thanked her, he encouraged the audience to sing along with him the last 16 bars of “Oklahoma!” People looked uneasy. But he started without them, his voice forceful and strong. And as he swung his arm high in the air with an imaginary lasso, his daughter watched him turn young again, and vital, and the theater was filled with life.

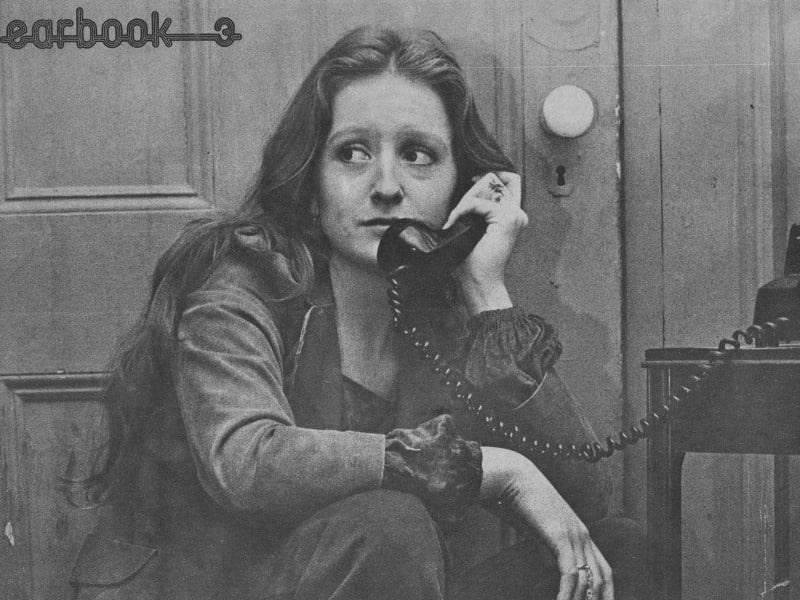

Photos: John Raitt and his daughter, Bonnie, in New York last week for his induction into the Theater Hall of Fame. (Sara Krulwich/The New York Times) (pg. C1); John Raitt in 1966, with his children Bonnie and Steven and their mother, Marjorie, in his dressing room at the Mark Hellinger Theater, when he was appearing in “A Joyful Noise.” (United Press International) (pg. C8)

(Edit: saved this article but couldn’t retrieve the photos)

Source: © Copyright The New York Times

Info: The Theater Hall of Fame

Visitors Today : 772

Visitors Today : 772 Now Online : 25

Now Online : 25