The blues never had a greater champion than Dick Waterman

In the music business, they often refer to performers as “the talent” and their recordings as “product.” Dick Waterman, the Boston-bred agent, promoter, and photographer who died Jan. 26 at age 88, saw the musicians he represented as something else — friends.

I’m deeply sorry to mark the passing of my friend, Dick Waterman, who made such a huge impact on the lives and careers of so many great blues artists, championing them as people as much as their music, booking and managing them with great care, integrity and skill. He gave me my start as well, going on to book and represent me for 15 years. He was also a renowned photographer who published a book and his wonderful photographs of some of our most legendary roots artists… He was an incredible storyteller, popular columnist in the local Oxford (Mississippi) Eagle and packed a great deal into his 88 years. We are so sorry to lose him and I am deeply grateful for the gifts he gave me and the life he lived. My sincere condolences go to his wife Cinda and all his family.

Dick published a book of rare photographs and personal recollections called “Between Midnight and Day: The Last Unpublished Blues Archive” in 2003. While the book itself is out of print, you can learn more about it here: http://tinyurl.com/yduhh6sa and read an excerpt (below) from the preface I was honored to contribute.

To learn more about his life, you can check out his biography, “Dick Waterman: A Life In Blues” written by Tammy L. Turner. https://www.upress.state.ms.us/Books/D/Dick-Waterman

— Bonnie

From Preface:

My friendship with Dick developed as closely as did the ones with the many blues artists we both adored. Through his connection I received the education and gift of a lifetime, hanging and learning about life and the music from all my heroes as well as being given a job I’d love for the rest of my life. Within a couple of years, I was opening for his acts and Dick went on to manage me for the next fifteen years.

While so many mostly white, middle class Blues aficionados seem to obsess about only the actual Blues recordings, huddling around their hallowed 78s, speaking in hushed tones about this or that obscure song, the living, breathing scions of the music walk among us. Often forgotten, neglected and long occupied in jobs other than music– farmer, porter, you name it, ..having given up on the idea of recognition of making a living in music, suddenly their lives are transformed by being ‘rediscovered’ during the heralded Folk/Blues revival of the mid-1960s.

After starting his own management and booking agency, Avalon Productions, Dick knew the meaning of rent money, medical bills, proper billing and payment. How to get a person from some small town in the Delta up to the big east coast cities for the gigs and back. He knew how to help these often rural, unsophisticated geniuses fare in the alien, impossibly whirlwind world of the folk/blues festival and concert circuit.

By gathering so many greats under one roof, Dick was able to collectively bargain to ensure each artist got to play the best gigs and be paid what they deserved. He steadfastly guarded every aspect of his artists’ professional life and was often the family’s solid rock during personal crises as well.

For helping raise the quality of life for so many artists with whom he worked, for reminding the white progeny of these mighty scions wherein their debt lies, for refusing to compromise probably at the expense of his own advancement, taking the high road and loving the people as well as the music, Dick has helped shepherd the Blues to a place in history truly befitting its worth.

For this, and for the gift that are these extraordinary images and reminiscences brought together in this book, we thank you.

Bonnie

Born in Plymouth and educated as a journalist at Boston University, Waterman fell into the folk scene in Cambridge in the early 1960s. His role in rediscovering the long-lost musician Son House in 1964 led to a lifetime in the blues.

Waterman brought several living legends to the Newport Folk Festival. He befriended the Rolling Stones and shot rolls of photos of a young Bob Dylan. He got Arlo Guthrie his first gig and encouraged Bonnie Raitt to launch her career. In 2000, he became one of the first non-performers inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame.

After he published “Between Midnight and Day” (2003), his book of photographs of Skip James, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Muddy Waters, and many more, Waterman told “Fresh Air” host Terry Gross that he had a hard time listening to his friends’ records after they were gone.

“It’s more than music to me,” he said. “When I hear these men, I remember their after-shave lotion. I know what they drank. I know what kind of cigarettes they smoked.

“When I listen to them, they don’t come to me as musical notes. They come back to me as people.”

tip: most convenient way to listen while browsing along is to use the popup button of the player.

Waterman grew up in an affluent Jewish household. His father was a doctor: “He got up in the morning and made sick people not sick,” Waterman recalled in “Dick Waterman: A Life in Blues” (2019), a conversational biography written by Tammy L. Turner.

He wanted to be a sportswriter but found himself covering the folk scene around Club 47, the small Cambridge coffeehouse that would become Passim, for Dave Wilson’s biweekly newsletter Broadside. While covering Newport for the National Observer in 1963, he was “totally captivated” by Mississippi John Hurt, a blues singer and guitarist who had recorded in the 1920s, then “vanished” for decades.

Waterman began helping Hurt, McDowell, and others land engagements in and around Boston, including a packed weeklong run for Hurt at Cafe Yana near Fenway Park, which serendipitously took place just days after Hurt appeared on Johnny Carson’s “Tonight Show.” A few years later, Waterman would name his burgeoning agency Avalon Productions after Hurt’s hometown.

In June 1964 Waterman joined fellow blues enthusiasts Phil Spiro and Nick Perls on a drive to Mississippi, in pursuit of a tip that Son House — a contemporary and friend of Charley Patton, the “Father of the Delta Blues” — was alive and well and had been spotted in Memphis. House had given up music in the 1940s and was using his given name, Edward.

Traveling in a Volkswagen Beetle with New York plates, they picked up a local minister who was an old acquaintance of House. On the backroads they encountered some hostility, as Waterman recalled in Eric von Schmidt and Jim Rooney’s “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down” (1979), the definitive book about the Cambridge folk years. This was the Freedom Summer, when white students from the north were volunteering in Mississippi to encourage Black citizens to register to vote.

When the Reverend Robert Wilkins got out of the car to ask for directions to a connection’s home, Waterman recalled, two “big, heavy, beefy, red-faced guys” stared at him, and then “spat straight down in contempt.

“They just looked at him, full of loathing and hatred. The air just crackled. They finally said, ‘Third farm down,’ and they turned and walked away.”

The day the group cracked the code about House’s whereabouts — he was actually living in Rochester, N.Y. — was the same day the activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan. Those parallel stories were told in “Two Trains Runnin’,” a 2016 documentary from director Sam Pollard that aired on PBS.

Though House in his younger years had been an influence on both Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters, Waterman soon learned that he’d forgotten how to play his own songs. He enlisted his friend Alan Wilson, the blues-crazy Arlington native who would soon cofound the band Canned Heat, to work with one of his heroes.

“They sat knee to knee with their guitars,” Waterman told Terry Gross. “So really, Al Wilson taught Son House to play Son House.”

During his Cambridge years, Waterman was known as the man to see if you were hoping for an audience with the masters of the folk blues. He’d grown up, as Turner points out in her biography, in a house “with a pineapple, the symbol of hospitality, ornamenting the front door.”

In his 2020 book “Looking to Get Lost,” the music historian Peter Guralnick recounts his awkward visit with Skip James at Waterman’s apartment.

James, another historic figure who’d just been rediscovered, made music that “struck me as unfathomably strange, beautiful, and profound,” Guralnick writes. Despite the fact that the shy 21-year-old had never interviewed anyone before, “I felt an obligation to seek him out.”

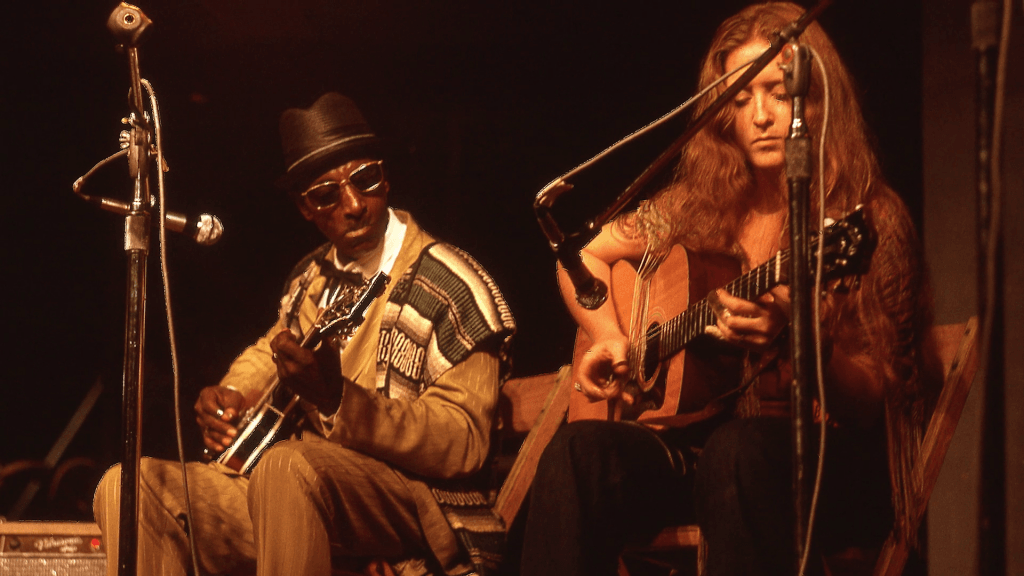

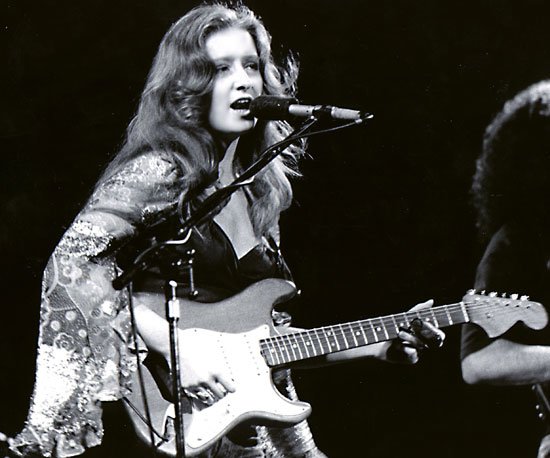

Waterman introduced Raitt, who was similarly mesmerized by the elder bluesmen, to House, McDowell, and Howlin’ Wolf. In fact, the two blues fans, Waterman and Raitt, kissed for the first time in a car outside MIT’s radio station, where they’d taken Buddy Guy for an interview. Their romance didn’t last long, but their professional relationship carried on for years.

Over time, Waterman had plenty more adventures in music. In the early 1970s he booked the acts at Joe’s Place in Cambridge, where a young, all-but-unknown Bruce Springsteen became a regular. Van Morrison once asked Waterman to be his manager. (He declined.) When John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd were forming the Blues Brothers, they consulted Waterman for help in putting the band together.

For Waterman, who lived his last decades in Oxford, Miss., it always came back to the blues. Driving back east from California with Son House during a 1965 tour, he found WBZ’s 50,000-watt broadcast on the dial somewhere in the Midwest and tuned into Jefferson Kaye’s Sunday folk program. When the DJ played House’s newly recorded version of “Death Letter,” Waterman had to explain to his passenger that he was hearing himself on the radio.

“I had a surge of just being elated,” Waterman recalled. “It was like the greatest three minutes of my life.”

About The Author

Dick Waterman, a steward and chronicler of the blues, dies at 88

© Michael Loccisano /Getty Images

Dick Waterman, a steward and chronicler of the blues, dies at 88

February 1, 2024

He shepherded the comebacks of renowned bluesmen like Son House and Mississippi John Hurt, managed singer Bonnie Raitt for 15 years and documented the music scene in thousands of vivid photographs.

Dick Waterman, who helped safeguard a rugged pillar of American music, the blues, as a writer, photographer, manager and promoter, rekindling the careers of revered singers and guitarists like Son House and shepherding the work of younger musicians such as Bonnie Raitt, died Jan. 26 at an assisted-living center in Oxford, Miss. He was 88.

The cause was congestive heart failure, said K.T. Leary, a longtime friend and executor of his will.

Mr. Waterman was 28, writing for a Boston-area music magazine called the Broadside, when he discovered the blues one day in July 1963. He had grown up in Plymouth, Mass., more than 1,000 miles from the cradle of the blues, the Mississippi Delta. But while reporting on the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island, he caught a set from singer and guitarist Mississippi John Hurt, who had toiled in obscurity as a sharecropper, his records gathering dust in bins, before being located by musicologists and brought onto the stage.

Hurt’s Newport performance was a revelation, intimate and hypnotic. “I never saw anything like it,” Mr. Waterman recalled decades later. “A little old Black man with an acoustic guitar went out in front of 15,000 people and brought them all up on the porch with him. He was magic.”

For Mr. Waterman, the spell never really wore off. Over the next few years he set journalism aside and became a manager and promoter, helping bring new attention to a generation of older bluesmen who had been overlooked for decades, even as their music came to exert a pivotal influence on younger artists from Bob Dylan to Canned Heat, Cream and the Rolling Stones.

“Perhaps no one alive has known more blues masters more intimately,” journalist David Friend wrote in 2003, profiling Mr. Waterman for Smithsonian magazine. A 2019 feature for American Blues Scene called him “A Blues Savior,” noting that while ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax had lugged his recording equipment through the South a decade earlier, helping to ignite a folk music revival through his recordings of older bluesmen, it was Mr. Waterman who “pulled them out of ‘retirement’” and brought them up to the stage.

Mr. Waterman worked as a manager for prewar legends such as Hurt, House, Skip James, Bukka White and Mississippi Fred McDowell. He founded what is often described as the first blues-only booking agency, Avalon Productions. (He named it for Hurt’s Mississippi hometown.) He managed a younger generation of bluesmen, including Buddy Guy, Luther Allison, Magic Sam and Otis Rush. He promoted concerts for Bruce Springsteen, James Taylor and Cat Stevens. And he was credited with discovering Raitt, the Grammy-winning singer and guitarist, whom he met when she was a freshman at Radcliffe College and represented for 15 years.

Through it all, he carried a Leica or Nikon camera, taking pictures that serve as a vivid and intimate chronicle of popular music — Dylan, Joan Baez, Chuck Berry, Ray Charles, Eric Clapton, the Stones — and especially of the blues artists that he came to know and love. His photos capture an electric Guy, knees bent and eyes shut, picking the guitar at an outdoor concert in Cambridge, Mass.; House, dapper and fedora-clad, gazing into the distance next to the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia; Hurt, looking weary at the 1964 Newport Folk Fest, looking on as James plays backstage. (Within five years, both men would be dead.)

Mr. Waterman’s photos, direct and often poignant, reflected the intimacy and rapport he had with the musicians he chronicled and represented.

“Dick knew the meaning of rent money, medical bills, proper billing and payment; how to get a person from some small town in the Delta up to the big East Coast cities for gigs and back,” Raitt wrote in the preface to Mr. Waterman’s 2003 book “Between Midnight and Day,” a collection of his pictures and stories. She added that “by gathering so many greats under one roof” — Avalon Productions — “Dick was able to collectively bargain to [ensure] each artist got to play the best gigs and be paid what they deserved. He steadfastly guarded every aspect of his artists’ professional life and was often their [families’] solid rock during personal crises as well.”

Mr. Waterman started booking blues shows in early 1964, helping bring Hurt to Cafe Yana in Boston after seeing the musician at Newport. That summer, he embarked on a cross-country trip that made national news and cemented his place in blues history.

Accompanied by two other blues enthusiasts, Phil Spiro and Nick Perls, he set off for Mississippi in search of Son House, who had influenced bluesmen from Robert Johnson to Muddy Waters but vanished from public view. Although Lomax had recorded House’s singing and slide guitar playing for the Library of Congress, it had been two decades since anyone had reliably seen or heard from the musician.

Following tips and rumors, Mr. Waterman and his friends unsuccessfully searched the Deep South before learning that House had moved north and was living in Rochester, N.Y. That was where they found him, sitting on the front steps of his apartment building, according to a biography of the singer by Daniel Beaumont.

Over the next few days, the trio persuaded House that there was an audience for his music. He had no guitar, so they found him one to play, then recorded a demo that Mr. Waterman used to get House a spot in the Newport Folk Festival lineup. He soon got the musician a contract with Columbia Records, became his booking agent and arranged media coverage with help from his brother-in-law, an editor at Newsweek, which ran a story on House’s rediscovery.

Looking back on his odyssey through the South, which took place during a turbulent summer of civil rights demonstrations and Klan violence, Mr. Waterman said he was lucky to make it through the road trip unscathed. “We were three Jews in a yellow Volkswagen with New York plates, and we didn’t feel too welcome in Mississippi,” he told the New York Times in 2015. “The day we found out he was living in Rochester was the day those three [civil rights activists] were killed” near the town of Philadelphia, Miss. “We were in Rochester two days later.”

Mr. Waterman went on to manage House through concert tours and recording sessions, as the musician reached a wide new audience that had eluded him at the start of his career.

“He was the most intense person I ever worked with,” Mr. Waterman told The Washington Post in 2003. “I never sensed Son House was a paid entertainer. He brought total commitment, played the same for 15 people, 1,500 people, or 15,000 people. He’d say, ‘This is just a little old piece of blues and I hope you like it,’ and then he’d unleash it and it was like being under a waterfall. He’d start to play, his eyes would roll back in his head, the sweat would roll out on his face and he’d just go somewhere else, some other place in time.”

The younger of two children, Richard Allen Waterman was born in Plymouth on July 14, 1935. His father was a family physician, his mother a homemaker.

Growing up, Mr. Waterman listened to the New Orleans jazz of Louis Armstrong and Kid Ory, later developing an interest in calypso. He turned to writing, filing news stories for local papers, while working to overcome a stutter. “Stutterers are better writers,” he told his biographer, Tammy L. Turner. “You get to the written word and you shine it and polish it until you get the written word to say exactly what you want.”

Mr. Waterman enrolled at American International College in Springfield, Mass., dropped out in 1956 to serve a three-year stint as an Army cryptographer, and returned home to study journalism at Boston University. He worked as a reporter at the Bridgeport Post in Connecticut, covering sports and traveling to New York a couple of times each week to listen to folk music in Greenwich Village, before settling in Cambridge and freelancing for the Broadside.

In the mid-1980s, Mr. Waterman moved to Oxford, where he booked concerts, wrote a newspaper column and stashed many of his music photos in drawers and closets around his home. A few were displayed around the city, and while their presentation was modest the images caught the eye of Chris Murray, the director of Washington’s Govinda Gallery, who was visiting town and soon began representing Mr. Waterman. He recorded Mr. Waterman’s stories, compiled his photos, published his book and organized the photographer’s first gallery show.

Survivors include his wife of about two decades, the former Cinda Shedore, and his sister.

After he retired as a manager, Mr. Waterman was interviewed for documentaries like “The Blues” (2003), a seven-part PBS series produced by Martin Scorsese. He was quick to dispense stories as well as advice, said Friend, who stayed in touch with Mr. Waterman after profiling him for Smithsonian magazine. In an email, he recalled a dinner in 2012 when Mr. Waterman offered guidance to his son Sam Friend, now a New Orleans-based musician.

“There is no single authentic blues,” Mr. Waterman said. “You will find the blues that expresses your blues. It might be through Son House. It might be through early electric blues. It might be through Bonnie Raitt or Luther Allison or Eric Clapton. But don’t force it. Your blues will come to you.”

About The Author

Dick Waterman, Promoter and Photographer of the Blues, Dies at 88

Dick Waterman, Promoter and Photographer of the Blues, Dies at 88

February 8, 2024

A “crackpot eccentric Yankee” from Massachusetts, he revived the careers of long-forgotten Southern artists during the blues boom of the 1960s.

Dick Waterman, a beacon in the world of blues who as a promoter, talent manager and photographer helped revive the careers of a generation of storied purveyors of that bedrock American art form while lyrically documenting their journeys with his camera, died on Jan. 26 in Oxford, Miss. He was 88.

His niece Theodora Saal said the cause was heart failure. A native of Massachusetts, he had lived in Oxford for nearly four decades.

Through his company, Avalon Productions, which was considered the first management and booking agency devoted primarily to Black blues artists, Mr. Waterman provided overdue exposure — and income — to early blues luminaries like Mississippi John Hurt, Son House and Skip James.

He also shepherded the careers of a younger blues cohort, including Buddy Guy and Otis Rush, as well as one young white artist, the singer-songwriter and future Grammy Award winner Bonnie Raitt.

“Dick Waterman just may be the most knowledgeable man on the history of blues,” the music writer Don Wilcock wrote in 2019 on the website American Blues Scene. Mr. Waterman, he added, “sought out the originators of the genre, pulled them out of ‘retirement’ and presented them to a folk audience that to that point considered blues to be a footnote in the American musical history.”

As a manager and promoter, Mr. Waterman both reaped the rewards of the blues revival of the 1960s and helped usher it along. That movement was fueled not just by stars of the electric blues like B.B. King and Muddy Waters , but also by a generation of white devotees like the Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton and many others.

To Mr. Waterman, even the most traditional rural blues was far more than a relic from a lost era — a point echoed by Ms. Raitt in the preface to his 2003 photography compilation, “Between Midnight and Day: The Last Unpublished Blues Archive.”

“While so many mostly white, middle-class Blues aficionados seem to obsess about only the actual Blues recordings,” Ms. Raitt wrote, “huddling around their hallowed 78s, speaking in hushed tones about this or that obscure song, the living, breathing scions of the music walk among us.”

“Often forgotten,” she continued, “neglected and long occupied in jobs other than music — farmer, porter, you name it — having given up on the idea of recognition or making a living in music, suddenly their lives are transformed by being ‘rediscovered’ during the heralded Folk/Blues revival of the mid-1960s.”

Despite being from Massachusetts, Mr. Waterman eventually established roots in the rich musical soil of Mississippi, settling in Oxford. “Every Southern town,” he said in a 2003 interview with Smithsonian magazine, “has to have a crackpot eccentric Yankee.”

Richard Allen Waterman was born on July 14, 1935, in Plymouth, Mass., the younger of two children of Isadore Waterman, a family physician, and Hattie (Resnick) Waterman, who managed the home.

After a stint as a cryptographer in the Army, he enrolled in Boston University to study journalism. In the early 1960s, he worked as a sportswriter and photographer for newspapers in Florida and the Northeast.

A music lover from an early age, he became enmeshed in the folk scenes in Cambridge, Mass., and Greenwich Village in New York.

He was covering the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island in 1963 for The Broadside of Boston, a folk publication, when he witnessed the power of the blues in a performance by Mississippi John Hurt, who briefly recorded in the 1920s before returning to work as a sharecropper.

“I never saw anything like it,” Mr. Waterman was quoted as saying in the 2019 book “Dick Waterman: A Life in the Blues,” by Tammy L. Turner. “A little old Black man with an acoustic guitar went out in front of 15,000 people and brought them all up on the porch with him. He was magic.”

His career turned after he heard that Son House, a storied blues musician who had vanished from public view decades earlier, might be alive.

He and two fellow blues aficionados, Phil Spiro and Nick Perls, went on an extended scouting mission and found Mr. House living in Rochester, N.Y., retired after years of working as a railroad porter. They coaxed him to pick up his guitar once again, and before long Mr. Waterman was serving as his manager and securing him a contract with Columbia Records.

Mr. Waterman knew something of the business. In addition to his journalism pursuits, he had worked for Manny Greenhill, who managed folk singers like Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan and Joan Baez in the 1960s.

He started his own agency in 1965. “I formed Avalon to find work for the old bluesmen because they were the last ones hired with leftover dollars,” Mr. Waterman was quoted as saying in Dr. Turner’s biography. “I wasn’t going to stand for that. I hated that.”

As white artists found platinum success with their own take on the blues, Mr. Waterman took issue with the idea that they were pillaging a hallowed Black genre. “It was more white people who felt young English kids are getting rich on Black people’s money, and they would go to the bluesmen and they would plant the seed of negativity,” he said in an interview with the music writer Bob Gersztyn.

In fact, Mr. Waterman argued, most Black artists he knew welcomed the exposure — and the resulting revenue. “The idea that people were getting ripped off, all of that is about copyright and publishing,” he added. “That’s where the real money is, and a lot of Black people got really, really rich off of white people doing their material.”

As his older clients retired or died, Mr. Waterman shifted his attention to managing Ms. Raitt’s flourishing career during the 1970s.

He settled in Mississippi in the mid-1980s and wrote a column for a local newspaper before shifting to photography. He chronicled powerful moments onstage and intimate moments off with blues artists like Bobby Rush, Champion Jack Dupree and Hubert Sumlin, as well as musical luminaries like Ray Charles, Willie Nelson and Mavis Staples.

He is survived by his wife, Cinda Waterman, and his sister, Rollene Saal.

In the Smithsonian interview, Mr. Waterman dismissed his decades of lens work as “no more than a hobby.” In the same article, his friend Wiliam R. Ferris, a folklorist and a former chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, said that Mr. Waterman was being a tad too modest: “That’s like Faulkner saying that he was a farmer, not a writer.”

About The Author

Dick Waterman Passes at 88

Dick Waterman Passes at 88

January 29, 2024

Waterman was in the NBC studios with Son House in 1965 when Howlin’ Wolf became the first African-American bluesman to perform on national TV with the Rolling Stones on ‘Shindig!’

Dick Waterman was the silk thread that ran through the scarf that has warmed my life in blues, the fabric of my obsession with the genre since the mid-60s when he started his blues talent agency Avalon Productions.

Waterman had more firsthand information about classic Delta bluesmen than any person I ever met. As a booking agent, photographer, author, and music journalist he had a direct impact on advancing the careers of Mississippi John Hurt, Skip James, Junior Wells, Buddy Guy, B.B. King, Arthur Crudup, Rev. Gary Davis, Taj, Mahal, Robert Pete Williams, Jessie Mae Hemphill, Booker White, Otis Rush, Charley Patton, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Skip James, Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker, Sam “Lightnin” Hopkins, Willie Dixon, and Luther Allison.

He used to tell me that we all had an entry into the genre, those of us who weren’t born into it. Waterman’s entry was Son House. At my 2019 Call and Response Seminar at the King Biscuit Blues Festival, he captured the essence of Son House.

“He would lay the slide down on the guitar neck and set himself in the chair, and this calm would come over him. Then he would just rip the slide up the neck over and over and kind of explode. He had this deep fierce voice, and it just rolled out. The songs went for as long as he managed to sing: six minutes, 10 minutes. Then, the song would end with this ripping ending. He’d pause and slip back in the chair, take out his handkerchief, mop his brow, take the slide off his finger, and put it in his pocket.”

Waterman was in the NBC studios with Son House in 1965 when Howlin’ Wolf became the first African-American bluesman to perform on national TV with the Rolling Stones on Shindig!

I saw him introduce Son House at the 1970 Ann Arbor Blues Festival.

In 1970 I booked Arthur Big Boy Crudup through Waterman, labeling him The Father of Rock and Roll.

I saw him with his camera at virtually every blues festival I attended from the 1970s until 2019 when he spoke at my seminar. He stared out the window as I drove him back home to Cinda and said that was his last festival appearance. It was obviously an effort for him, and I knew in my heart it did it for me.

Bobby Rush has called Waterman “the best manager anyone could have.”

The great musical author Peter Guralnick once said of Waterman, “He could tell his performers if they were doing something wrong. He could tell them that as an equal.”

Marshall Chess himself told me, “I never got to know Dick well but our paths crossed many times over the years. I always had deep respect for his knowledge and honesty and true love of the blues. I do know that Wolf, Willie and especially Buddy thought he was the real deal and listened to him when he spoke. He was a special Blues Man and will be missed.”

Waterman was up close with pivotal artists in a most personal way. He changed their lifestyle from day laborers to full-time musicians with enough money to live in relative comfort. And he did this from the perspective of having a degree in journalism from Boston University and an ability to be extremely anecdotal. He could take you there.

“I’m a very bad interviewer,” he once told me. “The reason is if I’m talking to Little Milton or Bobby Rush or somebody that I know, we’re having a conversation between equals, so it’s not an interview. The interviewer should ask a question and then shut up.”

Neither he nor I ever took that advice.

About The Author

RIP Dick Waterman, keeper of the blues and my favourite columnist

RIP Dick Waterman, keeper of the blues and my favourite columnist

by Nik Dirga

January 28, 2024

Mississippi blues writer, photographer and keeper of the flame Dick Waterman has died, one of the most extraordinary columnists I ever worked with in all my years in journalism. He was 88.

Dick worked with some of the great blues legends starting in the ‘60s like Mississippi John Hurt and helped “rediscover” the forgotten Son House. He gave many struggling blue legends a second chance at a career and some sort of justice and support. He also photographed and hung out with pretty much EVERYBODY in the music scene at that time – Dylan, Jagger, Bonnie Raitt, Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King, Janis Joplin.

© Dick Waterman

There will and should be some fine obituaries taking in the whole sweep of his career. (Such as this excellent Washington Post one or this fine one in The New York Times) But when I met Dick Waterman, he was a columnist for the weekly newspaper I started working at in 1994, Oxford Town. It was the very beginning of my post-college career and I knew everything and nothing. The editor Chico had hired him and it was one of the best things he’d ever done.

Almost every week Dick would drop these fascinating columns and stories about his life in music, tales of the legends and the forgotten geniuses, peppered with his gorgeous black and white photos. His columns were candid, backstage stories of what the blues legends were really like, or about his own life. When I was asked to take over as Oxford Town editor, visits from Dick were always a highlight.

Not that it was always smooth – Dick Waterman would turn in his column as late as humanly possible, shuffling into the old-school layout room close to midnight with a sheath of pages, while the pressmen could be heard loudly grumbling in the back. Once he discovered fax machine technology he pushed it even further. I attribute my skill at editing some copy very, very fast to some of his columns.

But he was unfailingly gentle and kind, with a bit of the “distracted professor” vibe around him. His photograph stash was an astonishing treasure trove that he had really just started to understand and promote in the 1990s. At one point he let us use an amazing photo of B.B. King on the back of an Oxford Town t-shirt.

I was just a rather self-important and fumbling 25-year-old editor dude at the start of my own weird journalism career but Dick was always good to me, and honestly, it took me a long time to fully understand what an amazing “six degrees of Kevin Bacon” type character he was in the ‘60s music world. I’ve never met Howlin’ Wolf or Muddy Waters or Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, but hell, I knew Dick Waterman.

R.I.P. my friend Dick Waterman (1935-2024), who played a key role in the careers of Son House, Bonnie Raitt, and others.

— Ted Gioia (@tedgioia) January 27, 2024

Dick was also a skilled photographer & took this historic photo. https://t.co/7KBckSdB8I

When I left Oxford Town around 1997 to sow my wild oats back in California, Dick Waterman for some reason singled me out in his column in what is still, coming up on 30 years on, one of the kindest single acts of writing anyone has ever done for me. I include it not to brag, but to show what kind of man Dick Waterman was.

He wrote about a Mississippi journalism award I won and said, “For the second year in a row, the Best General Interest Column was won by Oxford Town editor Nik Dirga. To appreciate this feat, you have to understand that he doesn’t even think about his own column until the rest of the paper has been completed. Nik has already announced that he is leaving in a few weeks and my sadness at his departure is mixed with the joy of having had the pleasure of working with him.”

“If Tiger Woods is the best golfer in the world at the age of 21, I can only hope that I stick around to see what literary accolades will come forth for Nik Dirga. The best part of working with Nik is that he honestly does not know how talented he really is. I am over twice as old as Nik Dirga and he is the best editor with whom I have ever worked.

“I wish him well in his travels and know that I will be reading his byline out there somewhere.”

He didn’t have to write all that about me, I know now, and I’m sure no Tiger Woods. But he did write it.

I wish you well in your own travels now, Dick, where ever they may take you.

Photos from Dick’s website and the excellent book collecting his photos and essays that used much of the material from his columns, Between Midnight And Day: The Last Unpublished Blues Archive. It’s an absolute treasure of a book. A very good full biography of Dick was also written a few years ago, Dick Waterman: A Life In Blues, which filled in many of the gaps for me about Dick’s life.

Visitors Today : 67

Visitors Today : 67 Now Online : 0

Now Online : 0