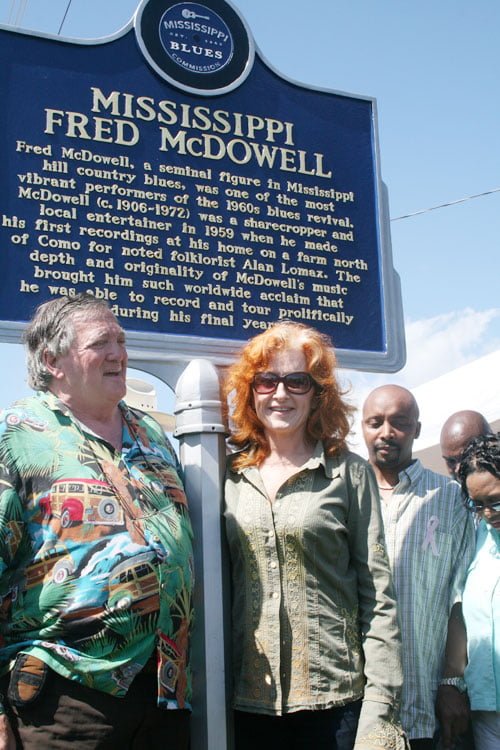

Bonnie Raitt attends Fred McDowell honor

Candice Ludlow – WKNO – 2009-05-08

The Mississippi Blues Trail Marker honoring Mississippi Fred McDowell was unveiled Thursday in Como, Mississippi. Candice Ludlow has more.

That’s the music of Mississippi Fred McDowell. Notice the resonating slide sound?

Como is where Mississippi Fred McDowell called home. It’s located 45 miles south of Memphis along Highway 55.

Mississippi Fred McDowell was born and raised in Rossville, TN, just outside of Memphis in the early 1900’s. He learned to play slide guitar from his father’s cousin who used a steak bone to slide along the frets as he played. Later, Mississippi Fred McDowell used a bottleneck slide.

Dick Waterman was McDowell’s manager during the 60s.

“He represents what’s called the hill country style. There’s the delta style of Charlie Patton, Son House, Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters and that type that went up to Chicago. There’s a hill country style that comes from Fred. It’s really most prevalent in Como, Senatobia, Holly Springs,”

Dick Waterman said.

It was sweltering hot on Main Street, a two-lane road through town with brick storefronts. Approximately 200 people were fanning their faces as the dedication began with students from a local high school playing and singing one of Mississippi Fred McDowell’s songs.

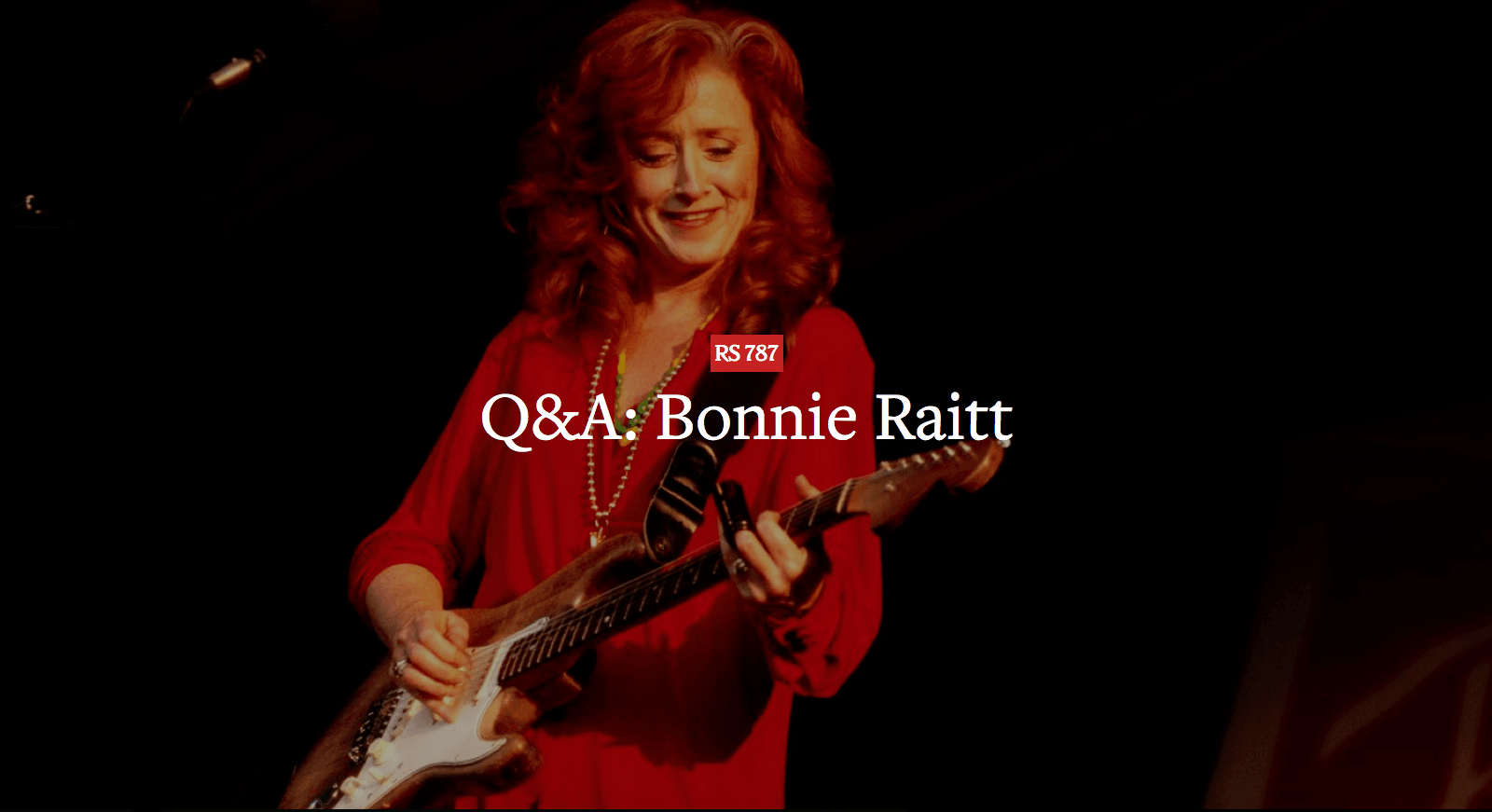

Grammy award winning singer-songwriter Bonnie Raitt made a special appearance at the dedication for her mentor.

“Well, he was one of the first blues artists that I got to meet, and I fell in love with his music from the first time I heard it on record. To have the honor and privilege to be able to be friends and tour with him in my early career was a gift I think like no other. His style of slide playing and his rhythm playing influenced me tremendously. I don’t know why we hit it off so much, but we just loved each other very much. It was a big loss when he passed when I was only 22, so it means a lot to me to be able to be here today.”

“Well, I’m so happy to hear that they’re doing this blues trail with 150 markers, elevating the music of blues and culture to the rest of the world. It’s been long overdue. Mississippi Fred McDowell is a giant in blues and there are so many other people that deserve that attention,”

Raitt said.

Photo’s © by Tony Lax

Eventually, there will be 150 Blues Trail Markers throughout Mississippi and in states connected with the blues from Mississippi. The first three blues trail markers were unveiled in 2006 in Holly Ridge, Greenville and Greenwood. The first Mississippi Blues Trail marker to be placed out of state was done so today at Third and Beale.

Shows Mississippi blues singer, Fred Mc Dowell, singing and talking about his blues. Includes scenes of the area which helped to shape his country blues.

Blues Maker – by Univ Of Mississippi – Published 1969

For WKNO News, I’m Candice Ludlow in Como, Mississippi. © Copyright 2009, WKNO

Source: © Copyright WKNO 91.1FM

Mississippi Fred McDowell

McDowell was born in Rossville, Tennessee, near Memphis. His parents, who were farmers, died when McDowell was a youth. He started playing guitar at the age of 14 and played at dances around Rossville. Wanting a change from ploughing fields, he moved to Memphis in 1926 where he worked in a number of jobs and played music for tips. He settled in Como, Mississippi, about 40 miles south of Memphis, in 1940 or 1941, and worked steadily as a farmer, continuing to perform music at dances, and picnics. Initially he played slide guitar using a pocket knife and then a slide made from a beef rib bone, later switching to a glass slide for its clearer sound. He played with the slide on his ring finger.

While commonly lumped together with ‘Delta Blues singers,’ McDowell actually may be considered the first of the bluesmen from the ‘North Mississippi’ region – parallel to, but somewhat east of the Delta region – to achieve widespread recognition for his work. A version of the state’s signature musical form somewhat closer in structure to its African roots (often eschewing the chord change for the hypnotic effect of the droning, single chord vamp), the North Mississippi style (or at least its aesthetic) may be heard to have been carried on in the music of such figures as Junior Kimbrough and R. L. Burnside; as well as the jam band The North Mississippi Allstars, while serving as the original impetus behind creation of the Fat Possum record label out of Oxford, Mississippi.

The 1950s brought a rising interest in blues music and folk music in the United States, and McDowell was brought to wider public attention, beginning when he was discovered and recorded in 1959 by Alan Lomax and Shirley Collins.[1] McDowell’s recordings were popular, and he performed often at festivals and clubs. McDowell continued to perform blues in the North Mississippi blues style much as he had for decades, but he sometimes performed on electric guitar rather than acoustic. While he famously declared “I do not play no rock and roll,” McDowell was not averse to associating with many younger rock musicians: He coached Bonnie Raitt on slide guitar technique, and was reportedly flattered by The Rolling Stones’ rather straightforward, authentic version of his “You Gotta Move” on their 1971 Sticky Fingers album.

McDowell’s 1969 album I Do Not Play No Rock ‘N’ Roll was his first featuring electric guitar. It features parts of an interview in which he discusses the origins of the blues and the nature of love. (This interview was sampled and mixed into a song, also titled “I Do Not Play No Rock ‘N’ Roll” by Dangerman in 1999.) McDowell’s final album, Live in New York (Oblivion Records), was a concert performance from November 1971 at the Village Gaslight, Greenwich Village, New York.

McDowell died of cancer in 1972, and was buried at Hammond Hill Baptist Church, between Como and Senatobia. On August 6, 1993 a memorial was placed on his grave site by the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund. The ceremony was presided over by Dick Waterman, and the memorial with McDowell’s portrait upon it was paid for by Bonnie Raitt, Dick Waterman (agent)and Chris Strachwitz (Arhoolie Records). The memorial stone was a replacement for an inaccurate and damaged marker (McDowell’s name was misspelled) and the original stone was subsequently donated by McDowell’s family to the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale, Mississippi.

Source: © Copyright Wikipedia

Singer Bonnie Raitt to Attend Como Blues Trail Celebration

by Martha F. T. Garrison

Thursday, May 7 will be a very special day in Como. That’s when the town will become an official destination on the Mississippi Blues Trail. In an afternoon ceremony starting at 2, on the median of Como’s Main Street across from City Hall, a handsome blues marker honoring the late Mississippi Fred McDowell will be unveiled. Singer Bonnie Raitt, who credits Fred McDowell as having exerted a major influence upon her music, is one of the guests who’ll travel to McDowell’s hometown for this ceremony. After the unveiling, guests can stroll a short way down Main Street to hear live music and enjoy refreshments in the town’s public library and its adjacent Memorial Garden.

Features of the 2 p.m. unveiling ceremony on the median include performances by a group of 11th and 12th graders, who will sing McDowell songs. These young members of a jazz stage band and a jazz choir will travel to Como from their Columbus, MS boarding school, the Mississippi School for Mathematics and Science. These bright young people hail from various towns all over the state. Additionally, the “Como Mamas” group will sing several gospel selections. Representatives from two Como-area churches – Hunter’s Chapel, where McDowell often attended and sang, and Hammond Hill Baptist, where he is buried – will say the invocation and the benediction. Several of the late musician’s relatives and friends will be introduced at the Ceremony.

Following the unveiling ceremony, the reception in the public library and Garden will offer guests a chance to meet McDowell’s kinfolk and hear live music by the following performers: Nathaniel Warren of Texas, who’ll play and sing several McDowell numbers; R. L. Boyce & the Como Breakdown, a well-known bluesy band; and singer Mary Ann “Action” Jackson. Organizers of the concert and reception are Como’s librarian Melba Major, Como resident Beverly Findley, and several other volunteers. The reception and concert are funded by the library and the Como Civic Club. Margaret Logan, Jo Anne Billingsley, and various other members of the Como Garden Club will create the fresh flower arrangements to decorate both the library and the Garden.

McDowell’s blues marker will permanently grace Como’s Main Street median, and it will have information about him on one side, and a map of the entire Mississippi Blues Trail on its other side. The Chairwoman of the Como Historic Preservation Commission, Meg Bartlett, assisted by her fellow Commissioners, worked extensively with the Mississippi Development Authority in preparing for the placement and unveiling of the marker.

Noted blues expert, Professor Scott Barretta, host of the Mississippi Public Radio blues-music program, Highway 61, describes McDowell as follows: “Mississippi Fred McDowell is widely viewed by blues aficionados as the most talented artist of his generation to be “discovered” during the blues revival of the late ’50s and ’60s. McDowell moved to Como, Mississippi around 1940, and performed widely around the region, influencing local bluesmen, including R.L. Burnside. In the wake of his discovery by folklorist Alan Lomax in 1959, McDowell began performing on the festival and coffeehouse circuits including the Newport Folk Festival in 1964. McDowell’s slide guitar playing had already influenced young white artists, notably Bonnie Raitt, and in 1971 the Rolling Stones covered McDowell’s version of the gospel standard “You’ve Got to Move” on their album ‘Sticky Fingers.’ “

As musicians from all over the world know, Mississippi is synonymous with blues. “The repertoire of any blues or rock band is full of songs, guitar licks, and vocal inflections borrowed from Mississippi bluesmen…,” says a Blues Trail publication. No matter where you go in this state, you are never far from the home, birthplace, or burial ground of some famous blues artist. Besides Como, other Mississippi locations which are, or soon will be, on the Mississippi Blues Trail map include Walls (Memphis Minnie), Berclair (B.B. King), McComb (Bo Diddley), Holly Springs (R. L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough), Meridian (Jimmy Rodgers), and Vicksburg (the Red Tops). Many other Mississippi communities will have markers honoring such blues greats as Jelly Roll Morton, Pine Top Perkins, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Son House, and Robert Johnson. (For more information about the Mississippi Blues Trail, visit www.msbluestrail.org.)

In case of rain on May 7, the Como festivities will take place at 211 Main. The Como Historic Preservation Commission extends a cordial invitation to all – and especially to Mississippians, Memphians, and other Mid-Southerners – to come to Como to pay tribute to Mississippi Fred McDowell, and to celebrate this region’s rich musical heritage. To find out more about the Como celebration, call (662) 526-5283.

Blues Trail markers and the entire Blues Trail project are made possible by funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Mississippi Department of Transportation, the Federal Highway Administration, the Mississippi Development Authority/Tourism Division, and local contributions. Como’s marker honoring Fred McDowell received substantial local funding from the Panola Partnership, Inc., located in Batesville.

Info:

Mississippi Blues Trail Markers

Mississippi Blues Trail on Facebook But wait, there's more!

Visitors Today : 97

Visitors Today : 97 Now Online : 0

Now Online : 0