It’s four minutes before the taping of The Arsenio Hall Show, and Bonnie Raitt has lost something.

”Where’s my honey?” she asks plaintively, striding down a Hall hall. Following Raitt is her manager, Danny Goldberg, who has his own problems. He’s not sure he wants a reporter hanging around in the nervous minutes before the taping; then, too, another of his clients, Rickie Lee Jones, has shown up suddenly, and he wants to make sure she receives some of his dutiful attention as well. Nonetheless, Goldberg narrows his eyes and tries to concentrate on Raitt’s question.

”Now, Bonnie,” he says with a grim smile, ”by ‘honey,’ do you mean the stuff that soothes your throat, or that wonderful husband of yours?”

Raitt and Goldberg turn a corner in the maze of this Paramount television studio in Hollywood and the question is abruptly answered. ”There he is!” Raitt hoots, nearly bumping into actor, writer, and, yes, a real honey of a husband, Michael O’Keefe, who has been roaming the halls looking for his honey. They kiss, they grin, they look like what they are: newlyweds, married since April.

Everyone retreats to a tiny dressing room, where Goldberg is happy to report that in next week’s Billboard Raitt’s new album, Luck of the Draw, will remain a hit top-10-with-a-bullet success. With the first single from the album, ”Something to Talk About,” moving into the Top 40, Raitt has her second smash in a row — and her amazing comeback continues.

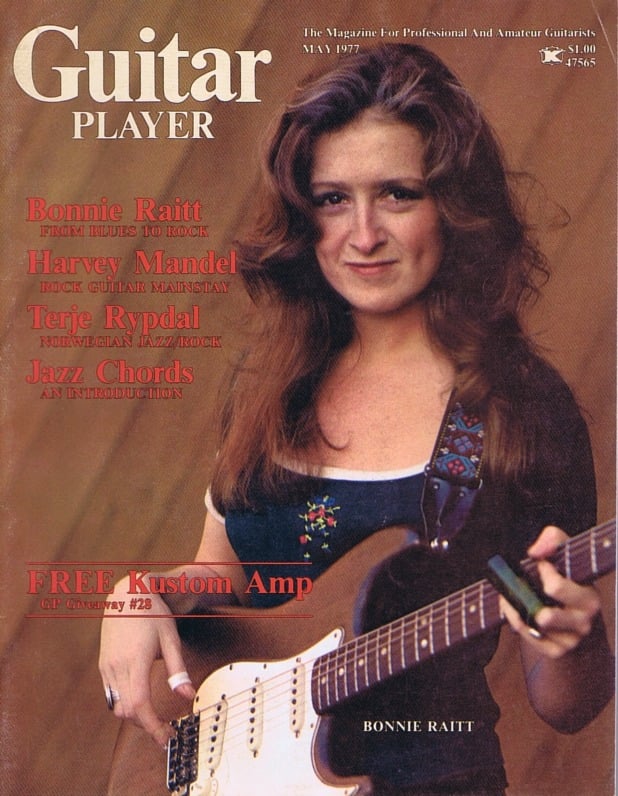

Before Bonnie Raitt released Nick of Time in 1989, she had received strong critical praise and the fervent admiration of a loyal following, yet in 18 years only two of her 11 albums had sold the 500,000 copies needed to make them gold records. Nick of Time changed all that by selling more than 2 million copies and bringing her a remarkable three Grammy awards — Album of the Year and best female vocals in both the rock and pop categories. At a time when many pop icons would rather prance and pose than play music, Raitt has come to stand for something more than just the great songs and progressive attitude that have always been her hallmarks. For the baby-boomer audience that has grown up with her and for the legion of younger fans she’s now attracting, the veteran of folk, blues, rock, hard times, and hard-won triumph transcends stardom: She embodies an emotional and artistic honesty and a survival instinct to be admired. And because of that, ironically, Bonnie Raitt has become a star at last.

She didn’t set out to be a pop star or even, exactly, a pop singer. Despite being the daughter of musical-comedy star John Raitt (Carousel, The Pajama Game), Raitt never embraced mainstream show biz. Given a guitar at the age of 8, she got hooked on folk music and the blues. By the time she was a teenager attending Radcliffe, she was moving up through the late-’60s Boston and Philadelphia folk scenes to establish her distinctive combination of bottleneck-guitar playing and no-bull frankness about romance, heartbreak, and bitterness.

From the start, Raitt was more wittily eclectic than any of her folk or blues heroes — her first two albums, Bonnie Raitt (1971) and Give It Up (1972), included songs from the Marvelettes, Robert Johnson, and Jackson Browne. Working out of Los Angeles, she struggled to achieve the commercial breakthrough that singer-songwriter contemporaries like Browne, Joni Mitchell, and the Eagles were enjoying, but without compromising her adventurous aesthetic. She made great music, but one after another, the albums flopped. The closest she came to a hit was a No. 57 single in 1977 — a cover of Del Shannon’s ”Runaway” that didn’t begin to suggest the depth and passion that her fervent following knew characterized her best work. The modest success of a song so atypical of her style seemed to throw her. ”Why the hell was that a hit?” she still asks. ”It made no sense to me.”

What followed was a series of increasingly uneven releases, each containing a few glowing high points. It wasn’t until Don Was, who produced Nick of Time, that she connected with someone who knew how to extract hits from her while clearing the way for her to make the straightforward, soulful music she’d always wanted.

”It touched me so much that Don was a real fan,” she says of the coleader of the group Was (Not Was), ”that he knew my work and respected it, and wasn’t trying to make me over into something else. I was able to use my past as a bedrock, and build something new on it.”

The out-of-nowhere triumph of Nick of Time has expanded her audience so dramatically that she is both surprised (again) and grateful. ”It’s unbelievable the way people react to me now,” Raitt says, laughing. ”It’s like I’ve become some living proof that there is justice in the world.”

At the Arsenio taping, Raitt and O’Keefe barely react to the good news about Luck‘s continuing commercial success, because her honey has Raitt in stitches doing a masterful impersonation of Martin Short doing a masterful impersonation of Bob Dylan as a rabbi. It’s easy to see why they get along: They’re both fast-talking wiseacres who like to discuss everything except the music biz, and their conversation zips from Zen (O’Keefe is a serious student of the stuff) to Berkeley in the Sixties, a PBS documentary they had loved the night before.

The taping goes well (Arsenio:””What does (winning all those Grammys) mean to you?” Bonnie: ”What it means is I get to smile a lot more”), and Raitt and her touring band perform rousing versions of two new Luck songs, ”Something to Talk About” and ”I Can’t Make You Love Me.” Backstage, the green room is filled with hangers — on and the show’s other guests, including Twin Peaks‘ Lara Flynn Boyle, out to promote her new film, Mobsters. Boyle is wearing a black sequined minidress which three women, any one of whom might be her mother, take turns yanking at, foolishly optimistic about the chances of forcing it to reach midway down her thighs.

”You look fabulous,” says one of the women.

Boyle, staring at the monitor as Raitt performs, murmurs, ”Yeah, well, I wish I looked as good as she sings.”

Raitt is sitting in a dark little grotto of a hotel restaurant off Sunset Boulevard, not far from where she and O’Keefe live, in the Hollywood hills. Relaxed and cheerful, she doesn’t look like a performer who’s just finished a month-long tour of Europe and is about to launch an extended series of American dates. Her pale skin is swirled with a mixture of freckles and wrinkles; she looks at once younger and older than her 41 years.

”I’ve always been very self-conscious about my looks,” she admits, ”and even more so now, when I’m being recognized, more and more people are coming up and talking to me and checking me out up close. I guess I feel that I look older than I feel, and in a way it’ll be a relief to reach an age where I can be all wrinkly because I’m supposed to be all wrinkly.” As a result, she seems genuinely alarmed at the prospect of being on the cover of this magazine. ”Oh, no — you don’t want me on the cover, do you?” she pleads. ”But you need young, beautiful girls to sell magazines! I mean, I’m worried your circulation will drop, and it’s such a nice young magazine!”

Indeed, Raitt’s compulsive modesty makes it difficult to secure new pictures of her — she routinely declines to be photographed — but that is the opposite of classic star vanity. ”You’re not dealing with Cher here,” says manager Goldberg. ”Bonnie is not the kind of person who thinks of herself as a walking media event, who wants to have her every move and expression documented.”

Perhaps looking to steer the subject away from her appearance, Raitt starts talking about Suzanne Pleshette, at a nearby table. ”She’s great — she’s got that rough, sexy voice,” she whispers. ”Anyone who managed to make Bob Newhart seem like an ideal husband — that’s a good actress, right?” Then Peter Boyle (The Dream Team) stops by to say hello. He and Raitt had met at various political rallies but haven’t seen each other in years. ”Hey Pete, you’ll be pleased,” says Raitt. ”I married an Irishman, and one with a great ass, too!” ”It’s an ethnic trait, I believe,” says the Irish Boyle.

After he leaves, Raitt mumbles something about the crazy world of show business, and offers opinions on everything from Roseanne Barr (”Why do people give her such a hard time? She’s a really smart, very up-front feminist. She’s always been nice to me; I barely know her, and she and Tom sent us flowers for our wedding”) to Thelma & Louise: ”Wasn’t it wonderful? I cheered and clapped involuntarily when Susan Sarandon shot that guy who was trying to rape Geena Davis — Michael looked at me like I was from the moon. I’ll bet a movie like Thelma & Louise will change some people’s lives, especially women’s, for the better.”

Raitt’s strong opinions, taken with the steely, unsentimental music on Luck, should allay any fears that her recent good fortune is turning her into a softy. Luck moves beyond the sort of my-baby-broke-my-heart songs that used to dominate Raitt records to grapple with questions of commitment and marriage. The most moving of these is ”One Part Be My Lover,” which she cowrote with O’Keefe.

”People ask me if I’ve lost my edge because of all the good things in my life now,” she says. ”Well, no matter how nice things get, I’m not gonna turn into John Denver and start writing ‘Rocky Mountain High’ — you don’t have to worry about that.”

She grins a little grimly. ”You know why I say that? Because no matter how popular I may get, I just don’t relate to the mainstream. My parents were like that, and it’s the way I felt when I was a kid, when Vietnam War protesters felt that the world was divided into Us against Them. Basically, I still feel that way, I think. The rest of the world is this jingoist, mean mess.”

If her new success has caused Raitt any problems, they have to do with adjusting to the intense examination that pop stardom brings. Soon after expressing these opinions, for example, she starts worrying whether she should be speaking out so forcefully. ”I used to express my opinions virulently — partly because I never believed people were reading what I was saying,” she says. ”But most of the time I feel a desire to be more closed-in since I got more famous. The glare of the spotlight is more powerful than I was expecting, and I can see now where spouting off about people can really hurt them. I started going out with Michael just as I was becoming more well known, and seeing my personal life written about really threw me. My life was never under that kind of scrutiny before.”

Raitt grows more somber, because she knows where this line of chatter is inevitably leading — to that most highly scrutinized aspect of her recent life: her newfound sobriety after many years of heavy drinking and fitful drugging. Her low point came about five years ago, when, having been dropped by her career-long label, Warner Bros., she was without a record contract, romantically bereft, and ”just about broke.”

”I’d go to visit my father, and I think he was really scared, because he saw me collapsing inside myself, right in front of his eyes. I mean, I wasn’t stumbling around, doing a Foster Brooks-drunk thing, but I was bloated and depressed and I wasn’t responsive. I couldn’t think beyond myself, about how miserable I was. It was easier to deal with life if I was loaded for at least half the day.”

In early ’87, Raitt finally entered a substance-abuse program. You can hear in her voice a profound relief mixed with guardedness when she speaks of it. ”You’re not supposed to talk much about these programs — that’s why they’re anonymous. But I needed to get back some self-respect. And it was as if, having taken that first step toward getting sober, I was rewarded. I got signed to Capitol and hooked up with Don Was and we made Nick of Time; then I met Michael and fell in love. Then the Grammys, and…” She takes a sip of cappuccino that’s getting cold. ”I know it sounds like a bad movie, but I’m really glad I decided to stick around and enjoy my life and the people around me.”

The people around Raitt include, most devotedly, her parents, with whom she has remained close throughout everything. They are divorced — her mother, Marjorie Haydock, lives in Connecticut, her father in Los Angeles. ”My dad is 74 and he’s out on the road, touring in Man of La Mancha. He does eight shows a week — it’s unbelievable! When we’re both in L.A., I go over to his house and swim in his pool while he jogs around it — and we sing Christmas carols to each other. Every time we do that, I wish I was videotaping it, because it’s such a crazy scene, but such a sweet one, too.” Father and daughter are considering doing a Broadway show together. ”The Double Raitts,” she laughs, ”wouldn’t that be great? I’ve talked with a Broadway production company and they think there’d be an audience for it. He’d sing some of my songs, I’d sing some of his, and we’d do a few duets.”

For now, though, there is the work of touring. Pushing aside her plate, Raitt lays her head on the table and emits a mock groan. ”Oh, it’s hard work!” Then her head pops up and she smiles. ”Before Nick of Time, I was bored with it, but not anymore, because after all those years of playing the same clubs in the same towns, I’m playing different halls — much bigger ones, with some new people in the audience who aren’t going to just be calling out for songs from my first album 20 years ago.” And, as always, Raitt tries to involve her audience with her political concerns. In a number of cities, as she has for many years, she will raise money for various left-liberal causes, ”especially abortion rights this time, that’s really the crucial issue out there right now.”

For so socially involved a performer, it’s interesting that Raitt avoids sloganeering in her work. ”I can’t write songs about what’s wrong with a country that seems to lack compassion for pain and suffering,” she says. ”I’ve never written one that works as both a statement and a piece of music. Besides, I never really know what I’m going to end up with when I write — it’s kind of haphazard. Marriage is the same thing — I have no idea what I’m doing, and that’s what makes it so exhilarating.”

Dinner is over, and Raitt goes over to compliment the pianist who has been playing discreetly dry versions of pop standards in the hotel bar. She introduces herself, but she needn’t have: ”I swear, I bought Luck of the Draw two days ago!” says the young fellow. As Raitt walks to the door, the pianist calls out, ”I’ll try playing ‘Nick of Time!”’

”Naw,” Raitt says over her shoulder, ”you’ll give yourself a hernia — it’s a real hard song to play on the piano. Stick to Cole Porter — he’s a better songwriter.”

Visitors Today : 75

Visitors Today : 75 Now Online : 1

Now Online : 1