Shake ‘Em On Down: The Blues According to Fred McDowell

A Documentary Film by Joe York & Scott Barretta

B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson, Howlin’ Wolf. When it comes to Delta blues, there’s no shortage of well-known names to cite. But there’s another region — and other musicians — to credit for Mississippi’s state-line-road-sign claim, “Birthplace of America’s Music.” One such example: North Mississippi’s Fred McDowell.

And thanks to a recent documentary by now-independent producer and director Joe York and Mississippi Blues Trail writer and researcher Scott Barretta, people across the world can learn to appreciate the bottleneck guitarist’s contributions. The celebrated, hour-long film gave even York and Barretta, longtime fans of McDowell, a newfound appreciation for Mississippians’ love of the arts, their native music and their hill country legend.

“Shake ‘Em On Down” was made for the Southern Documentary Project, a branch of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi. Since its premiere, the documentary has been played at multiple film festivals and on PBS as part of the Reel South series educating the country on the history of North Mississippi blues and McDowell’s crucial contribution to that vibrant tradition. The film’s name was taken from the title of a Bukka White song McDowell recorded several times.

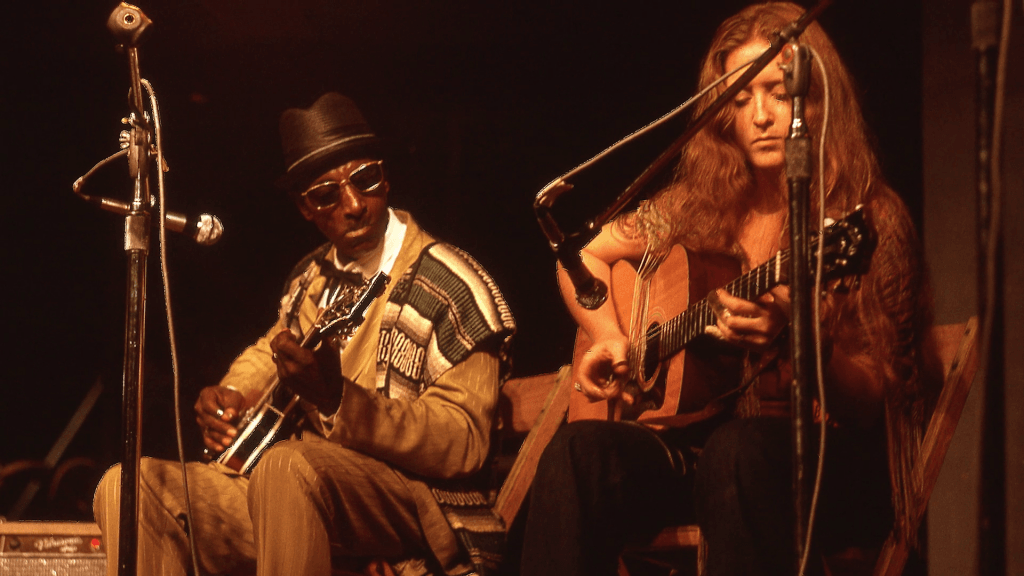

Born around the turn of the 20th century, Mississippi Fred McDowell mastered the slide guitar-playing style by performing at house parties between weekdays working odd jobs or plowing fields. In the late 1950s as McDowell’s name and music gained traction in the area, folklorist Alan Lomax — along with assistant Shirley Collins — made it his mission to record McDowell in Como, where the Rossville, Tenn., native had settled.

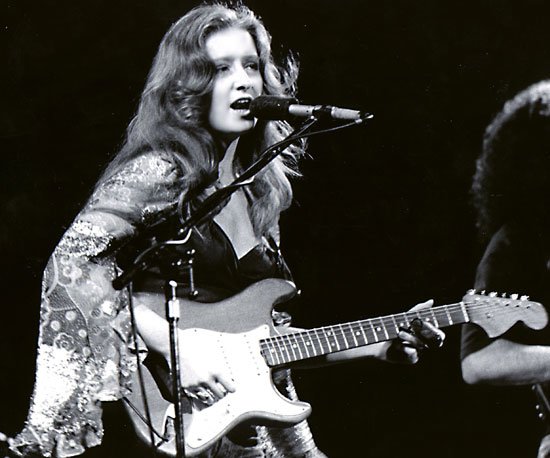

The 1959 recording sparked a career that carried McDowell to the Newport Folk Festival in the mid-1960s, to meet and mentor a young female artist named Bonnie Raitt, and to have his song “You Gotta Move” recorded by the Rolling Stones on their 1971 Sticky Fingers album.

At the height of that career, a short film about McDowell titled Blues Maker was made. Half a century later, York was working for the Southern Documentary Project, directed by Andy Harper, as well as producing Highway 61, a Mississippi Public Broadcasting blues program hosted by Barretta.

Right around the time York and Barretta were investigating the unique musical traditions of the Mississippi hill country for Highway 61, York discovered Blues Maker. With newfound footage, he and Barretta had a basis upon which to build an in-depth film about an artist they had long admired and respected. Two years and countless interviews later, “Shake ‘Em On Down” was finished.

“It’s one of the finest documentary films ever made on blues,” said Dr. William Ferris of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Ferris, a Vicksburg native, founded the Center for the Study of Southern Culture and is one of many voices captured on film by York and Barretta.

“To me, the craft of it is to somehow make all the different voices come into a conversation with each other so they’re telling you, the viewer, a coherent story,” said York, who likened the filmmaking process to completing a puzzle after having to create the pieces.

In addition to Ferris, “Shake ‘Em On Down” includes an appearance by blues legend R.L. Boyce, as well as Chris Strachwitz of Arhoolie Records, Raitt and even Collins, the former assistant of folklorist Lomax.

Though Lomax died in 2002, Barretta and York knew that Collins was still living in England. They reached out to her and, she invited them to her hometown just south of London for an interview. And Collins became, in York’s opinion, one of the most important voices in the film.

“It was amazing to be sitting in this beautiful home in England listening to this person talking about someone we had loved and admired and listened to his music forever,” York said. “The first time Fred ever played into a microphone and it was recorded, she was sitting three feet away from him. Here we are halfway across the world, and this lady is bringing this moment to life.”

Other crucial pieces of the documentary didn’t come together as easily. Because McDowell died in 1972, Barretta and York had limited footage with which to work. But, they struck gold in New York, where they discovered never-before-seen footage — about 40 minutes’ worth — of McDowell performing at the Newport Folk Festival.

“We looked through it, and we said, ‘Okay, we want like eight minutes of this footage to use in the film,’” York said.

But the price tag on the footage was right around $25,000.

“So, all of a sudden, you’ve found this treasure trove of material of this guy that you’ve been literally following around the globe,” York said. “You’ve been working on this for a year, and now you have this thing that’s incredible that you know needs to be in the film, but it costs about the same as a new car.”

Baffled, York and Barretta made a trailer to present to a group at a blues symposium held at Ole Miss. The three-minute preview incorporated a short, watermarked piece of that crucial footage — enough to catch the eye of audience member Ron Feder.

Feder, an alumnus of the Ole Miss law school and a frequent benefactor of arts-related programs in Oxford, approached York afterwards and expressed his desire to contribute to the making of “Shake ‘Em On Down.”

“And, I kid you not, within a week, we had a check from Ron Feder for $25,000,” York said. “He and his wife Becky, who has sadly passed on in the last year, became executive producers on the film.”

That contribution, in Barretta’s opinion, made the documentary.

“There were no photos, to our knowledge, of McDowell and Lomax together,” said Barretta. “And the opening scene from Newport was wonderful for the underlying story of how Lomax’s discovery of McDowell led to his becoming a well-known blues artist.”

Another triumph came when Bonnie Raitt, who learned her guitar-playing style from McDowell, agreed to be a part of “Shake ‘Em On Down.” Raitt’s former manager, Dick Waterman, had worked with McDowell in the ’60s and early ’70s and introduced the two. Waterman was one of many contacts that Barretta had made working in the blues field, and better yet, he was in Oxford.

“That was huge,” York said. “We knew we couldn’t do the film seriously without her being a part of it, because their relationship was so strong and, obviously, what she’s gone on to do with some of what she learned with Fred goes without saying.”

Stories like that of Mississippi Fred McDowell — a “major figure in American music,” according to Ferris — not only inspire but also educate.

“Because the blues is often associated with the Mississippi Delta, it is important that the public knows that other parts of our state also produced a rich blues heritage,” Ferris said. “Generations of Northeast Mississippi blues artists have been strongly influenced by Fred McDowell’s bottleneck blues.”

But it was not just McDowell’s prominence that drew people to him, according to York. After all, people who didn’t have to give money or encouragement to Shake ‘Em On Down did so nevertheless.

“To me, it was the process building those relationships and working with those people and seeing how Mississippians are willing to come together to help tell inspiring stories about Mississippi,” York said. “It’s a testament to the incredible spirit and will that exists among the Feders and, really, of lots and lots of people in Mississippi who support the arts and one another.”

The Oxford Eagle

The Southern Documentary Project

PBS

Visitors Today : 55

Visitors Today : 55 Now Online : 2

Now Online : 2