If you’re a talented singer on the way to the top, like Bonnie Raitt, maybe you gotta leave SOME things behind in Boston.

Bonnie Raitt breezed into town over the holidays, flushed with the success of a performance at the Glassboro State (New Jersey) Blues Festival, the safe return of an old boy friend from the devastated city of Managua, Nicaragua, and a chance to be among friends for a week or so before a longish junket to the West Coast. New Year’s Eve was spent at Jack’s where Chris Smither provided the music and the booze flowed freely. For a while, there was the Bonnie we knew back in 1970: drinking for the joy of it, loving for the hell of it, enjoying the music for what it was.

When a city breeds a talent that makes it big the city eventually loses that person. The big names in music become the property of the country after a while. Boston hasn’t been the breeding ground of as much talent as, say, Nashville but the Taylor family (James and Livingston, at any rate) and J. Geils of recent memory are now gone and Bonnie is following them out of the city. Although she says she tours only when she wants to, Bonnie Raitt is now out of town more and more often: at the Main Point in Philadelphia, at Max’s Kansas City in New York, the Ann Arbor Blues Festival, the Troubador in Los Angeles, Woodstock for one album, L.A. for another. A local music ad man said recently that “if Bonnie’s latest album doesn’t make it big, the next will and everyone in the business knows it.” Albums creep up Billboard’s charts, profiles appear in Newsweek, Rolling Stone and the Times and pretty soon the nights at Jack’s and Joe’s Place, the long drinking bouts are just pleasant memories.

The summer of 1971 was a good one for Boston. The old Phoenix and Boston After Dark were thriving, places like Jack’s and Joe’s were just starting. There was music on the Common every week and Cambridge had music in the streets every night. That summer, come to think of it, was the time of street music. You could still see J. Geils without having to fight your way through a mob of under-age pill-poppers. James Montgomery and his blues band could still blow the lid off Jack’s without causing a riot; Livingston was still in town; Spider John Koerner was just in from Denmark; and some fine and unexpected folks were turning up at Jack’s to jam. That whole three months—and it could be my imagination since the Phoenix staff, of which I was a part, made Jack’s its second home— seemed to swirl around Jack’s. Every evening started there and ended there unless you could struggle down the street to the Casablanca where they stayed open one hour longer.

First night I had a chance to talk with Bonnie was at Jack’s. Her following in the area was already sizable and there were plenty of Bonnie stories to go around: Bonnie at the Philadelphia Folk Festival stealing the show from her mentor, the late blues genius Mississippi Fred McDowell: Bonnie awing a crowd here and a drunken mob there; Bonnie playing with legendary bluesmen who called her friend and raved about her talents. And most of all, her drinking. That legend always proceded Bonnie and even Boston Phoenix sports writer George Kimball, one of the superb drinkers of our time, seemed a little in awe with the Raitt capacity to throw down bourbon straight. (A bartender from Max’s Kansas City where every hot drunk in the Big Apple congregates once asked me very seriously, “How can she play so well when she’s so damn blown?”)

The consensus was: “Don’t go boozing with Bonnie unless you have three days to recuperate.” It was never quite that bad but that first night was. They were all there: Bonnie, her boy friend, Hal Moore, the photo-journalist who escaped the destruction in Central America; Harper Barnes, the former editor of the Phoenix; Kimball; Phoenix writer Francie Barnard, now a White House correspondent; Vin McLellan, the former Phoenix city editor now a Los Angeles free-lancer, Dick Brown, the old New York Herald writer who was then the Phoenix’s ad manager. Mississippi Fred had stayed at Bonnie’s house while doing a local gig and Bonnie was just gearing up to do her first album so the conversation ran in that direction.

Bonnie was particularly bitter over the treatment accorded her friend, Mississippi Fred. Damn, she was given to saying, why can’t people understand that he is the real thing? How can they applaud what I’m doing and ignore him? There was an ache in her voice as she described her appearance with McDowell at the Philadelphia Folk Festival, a show where she was the hit and the aging (and dying) blues genius was all but overlooked. “I can understand why audiences can understand Fred’s music better through me than through the real thing but that doesn’t make it any easier to take,” she once said to me. “I sometimes think that if I were better they’d like me less. I just can’t always bring off the music I really like but maybe I whiten the music just enough to appeal to white audiences.”

The new album was another thing entirely. Bonnie excitedly described how it was going to be recorded up at a friend’s place in Minneapolis on a four-track machine with all her friends. Everyone thought that was very funky until someone (looking back through the booze that permeated the conversation it might have been me) suggested that a top-grade producer with an established reputation and a regular studio with a 16-track machine might be better. Bonnie wouldn’t hear of it. She wanted to do the album with her friends so that they could get some exposure and some money. “If I can’t make‘ the record the way I want to,” she would say later, “what good is doing it anyway?”

Bonnie is, above all else, charming—a description she’d probably reject but one that fits. She takes time with people and listens to them. One night at last summer’s Philadelphia Folk Festival, Bonnie had just finished her part of the show and was due at a party back at the hotel where the artists were staying. She took time, however, to talk to a college kid trying to book musicians for his school’s coffee house. The kid went through a long rap on how good the place was, how much they needed help and Bonnie listened, asking questions along the way. Finally she told him that her manager, Dick Waterman, did all her booking but she’d mention the college to him. Bonnie could have cut the kid off with a “see my manager” but she didn’t and the student went away satisfied and uncrushed. That’s a sense of grace lacking in many performers.

That same lack of pretense shows up in her father, John Raitt, and he had to struggle even harrier to maintain it. Raitt was a major star of Broadway and Hollywood musicals during the forties and fifties. A man of rugged looks and immense vocal abilities, he was the leading man in countless productions of the Carousel/Showboat/Oklahoma variety. But he basically refused to play the games required of stars at the time; the plastic world of Hollywood had no attraction for him. “My father was just never into that sort of thing at all,” says Bonnie. “He’s a simple guy; sorta straight. We don’t always communicate that well but I think he’s proud of me . . . hell, I know it.”

Raitt’s contempt (or lack of interest) in plastic California rubbed off on Bonnie and her two brothers. Bonnie hated the 1961 world of surfing and surfing music. She felt much more at home at the Quaker camp in the East where her father sent her every summer for six years.

I never fully realized the impact the camp had on Bonnie until one hangover-dominated-morning when we talked the blues and you could really see her drift off into the world of that place. “It was a big thing to havea blacklisted parent at that camp,” she says. “We were all baby radicals and the place was dominated by words like Selma. SNCC, and SANE. Everyone listened to Joan Baez and Pete Seeger. Everything was up-front, very political. You had to be aware of the political realities.

“But that wasn’t the only thing. I found my music there. I heard Mississippi John Hurt and Fred and John Hammond and that music became important to me. I taught myself to play the guitar so I could follow them.”

From the camp, the music and the political awareness led to Radcliffe for a brief period in 1969 (“because they didn’t have a phys. ed requirement and let you stay out at night”) and then down to Philadelphia where she worked for the American Friends Service Committee (“typing is a drag”) and finally started singing on her own in any number of dinky Philly bars and clubs. She came back to Cambridge just in time to get a boost from the city’s two alternative weeklies and the general ambience of the town in 1970 and ’71.

As I’ve said, the word on Bonnie was just spreading when we first met. I had never heard her sing so when Jack’s finally closed down that first night and a street party had run its course and we were firmly if drunkenly settled into someone’s living room I asked her to play some tunes. Bonnie picked up a guitar which had appeared from someplace, mumbling something about how drunk she was (knowing Bonnie she probably punctuated the comment with “Give me a break on this.”)

First the guitar sang: chords that flowed out of the Delta, notes that spoke of long-gone train whistles in the night. Then Bonnie’s voice: not husky like Diane Davidson’s or as powerful as Tracey Nelson’s but full and rich in pain and frustration and wasted tears. And that’s what was ringing in my mind as I went to sleep (passed out, really) that night: the beautiful echoes of the black South as interpreted and remolded by a young white woman of the North.

Then Bonnie was making music for the joy of it. The art and her relationship to it has subtly changed since then. The rent still gets paid by the music, as she puts it, but the realities of the business had intruded on the joy. The first album (“Bonnie Raitt” on Warner’s) failed in many respects although it had a certain funky, made-in-a-bathroom flavor to it. “That was one way to do a record,” she says now, “but I don’t think I’d do it that way again.”

The second album and most recent Raitt album – “Give It Up” – is more professional and more diverse musically. Bonnie is developing a keen sense for the best in other people’s material and she does her best work on tunes written by Jackson Browne, Eric Kaz, Joel Zoss, Chris Smither and Barbara George – a mixture of established and new writers. But it cost a summer of pain in the incestuous town of Woodstock, New York, where she recorded “Give It Up” at the famous Bearsville Studios. “A miserable damn place,” is how she describes Woodstock.

Now she’s moving further into “the Business” way of doing things. Her next album will be recorded in Los Angeles with the vastly-underrated band, Little Feat. Produced by Feat’s Lowell George and including material by Randy Newman and Joni Mitchell, it should be the most professional record she’s done yet. And it will probably propel her further up that mythical star ladder and make a lot of money for Warner Brothers.

The music business takes more out of someone like Bonnie than others. She likes to play bars and can no longer play them in the cities where she is well-known. Doing benefits for anti-war groups, women’s collectives and other Movement affairs was once a big part of her life but that has had to be cut back. She’d like to find out what’s happening politically in each town she visits but “I don’t have time to find out for myself anymore.” Cambridge is her home but she has to spend more and more time on the

road.

And the personal pain can be something else. She no longer sees her boy friend except for brief encounters like the one after the Managua earthquake. Other men can’t find a way into her life. “If I were to meet a guy I like,” she says “I couldn’t drag him along with me the way a guy can take a chick.” She now has all the burdens of juggling money and recording dates and bookings. It’s making her tougher than she cares to be.

Catch her at the right moment and she’ll tell you that “I’ve got to keep hold of myself. I don’t want to have to withdraw from life like James (Taylor) and (Bob) Dylan did. I love it too much.” That is the essence of Bonnie Raitt today: some of Bonnie yesterday and some of Bonnie that might be all mixed in together. Parts of the past — a concern for audiences, for making sure old blues artists get on bills with her, for playing with musician friends who need the bread, for keeping ticket prices down — remain but there are also visions of a future that could crush her as it has so many artists on the order of Taylor, Dylan and Joni Mitchell.

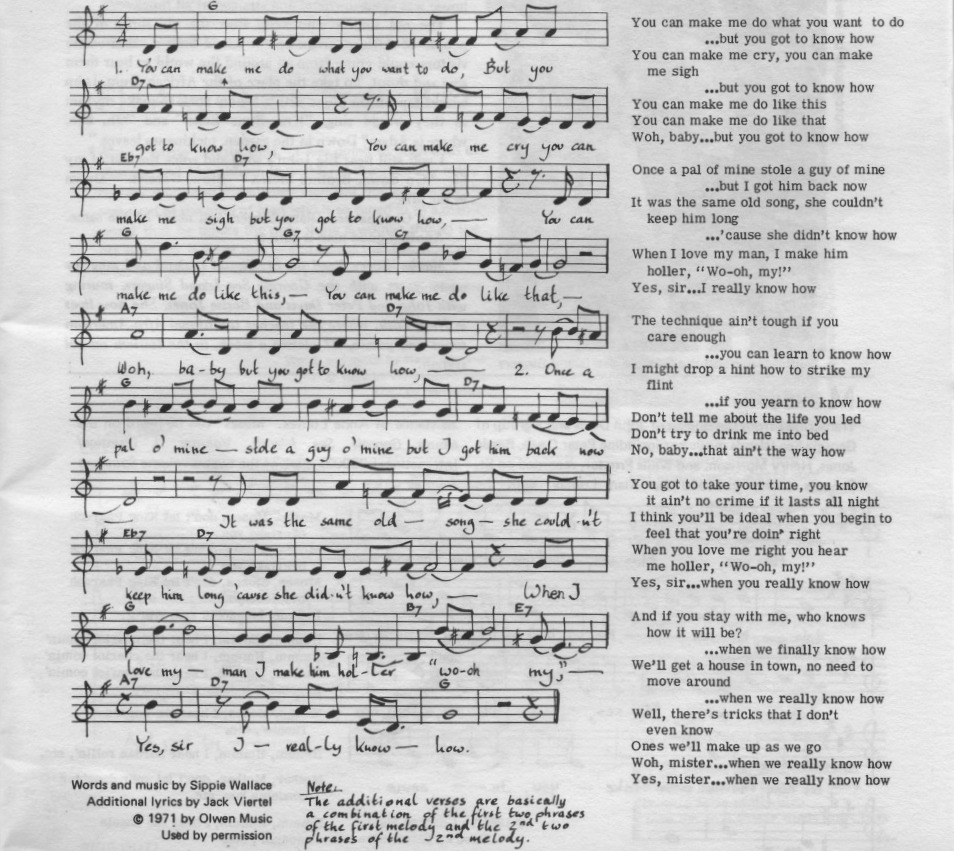

There are times now when I wonder if the Bonnie of a summer night in 1971 will ever return. That’s usually when I hear a story like the one now making the rounds about Bonnie and Dylan. At the party for those playing the Philadelphia Folk Festival this summer Dylan – who was on hand- asked Bonnie if he could play mouth harp with her at the Ann Arbor Blues Festival, scheduled for later in the year. Bonnie was due to play with Sippie Wallace, an aging blues artist. She thought about Dylan’s offer for a moment and then declined. Bonnie didn’t want to take away from what might be Sippie’s last day in the sun. It was a Bonnie Raitt decision.■

Charlie McCollum is a freelance writer who lives in Watertown.

Visitors Today : 71

Visitors Today : 71 Now Online : 0

Now Online : 0