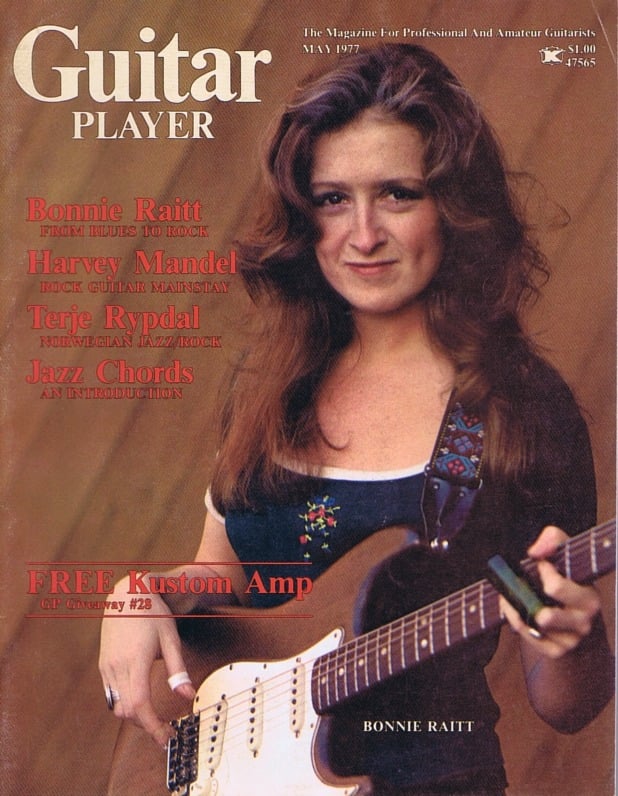

Cover photo by Neil Zlozower

Classic Interview

By Patricia Brody

BONNIE RAITT was almost a folksinger, part of the plethora of guitar-playing protesters of the Sixties led by Bob Dylan and Joan Baez. Sitting in her girlhood bedroom in a house atop Coldwater Canyon’s peacefully affluent Mulholland Drive, Bonnie, born in Burbank, California, in 1949, was inspired by loneliness to teach herself guitar. “If I’d been able to hang out with other kids, I’d never have gotten into it,” says the daughter of successful Broadway actor John Raitt, best known for his leading roles in musical comedies like Pajama Game, Oklahoma, and Carousel.

The Raitt house—last stop on the school bus route—though somewhat isolated and not particularly conducive to visits with friends, hardly seemed located within earshot of the whiney, mournful tones of a generation of blues guitarists whose techniques and repertoire Bonnie came to adopt. Blues developed far from what Raitt describes as the Los Angeles “blonde-streaked surf scene” whose “political and intellectual vacancy” drove her to a progressive Quaker boarding school in upstate New York. There, feeling more in her element among, as she calls them, “the precocious children of leftist lawyers and actors into modern theater of the absurd and Marxism,” Raitt listened to Pete Seeger records and expressed her own discontent playing Peter, Paul, And Mary and Kingston Trio-type laments on her guitar. “For years,” she recalls, “I wanted desperately to get old enough to be able to go to civil rights demonstrations and peace marches, be a beatnik, grow my hair, and have cheek bones like Joan Baez.”

Encouraged in a musical home where “my mother was my father’s accompanist, and we’d all sit around singing together,” plus five years of piano lessons, Bonnie first turned to guitar, a Stella given to her as a Christmas present by her parents and grandparents, at the age of ten. She enthusiastically pursued her hobby through several summers at camp, in Massachusetts, where her counselors inspired even more longing for contact with the outside world, with their exciting reports of musical events at the nearby Newport jazz and folk festivals.

Then, an album, Blues At Newport ’63 (on Vanguard, S79145) containing tracks by John Lee Hooker, John Hammond, Mississippi John Hurt, as well as several other blues and folk artists fell on Raitt’s fourteen-year-old ears with enough impact to permanently change the direction of her music. “From that point on,” she remembers, “I was split into two parts. One side of me was all Joan Baez, my early idol, or Childe-type ballads, while the other suddenly had to learn whatever the hell it was Mississippi John Hurt was doing on ‘Candy Man’.’’ Being Bonnie Raitt, she learned “Candy Man.”

An acceptance from Radcliffe College in Cambridge, Massachusetts—they didn’t have curfews there—further assured Raitt’s entanglement with the blues. Though she began by majoring in African studies with plans to do a community development, political organizing program, she soon came into contact with a leading figure of what she terms the blues “mafia.” Dick Waterman, manager and promoter for many blues artists and events, seems to have been the catalyst who turned Bonnie’s guitar hobby into a pursuit of somewhat greater intensity. It was at Waterman’s Cambridge apartment that Bonnie met Son House, the first in a long chain of encounters with aging blues giants who were to definitively shape the young woman’s entire career. She did not become a political organizer or a white Odetta (another of her childhood influences). The black woman with whom she is most identified is Sippie Wallace, a blues artist now in her eighties who has been making records since the Twenties, and many of whose songs—”You Got To Know How,” “Mighty Tight Woman”—have become Raitt standards.

Hindered, she says, by a voice more Judy Collins than Memphis Minnie, Raitt has worked continuously for nearly ten years to combine her evocative Delta-style slide guitar with her “white girl’s” vocals to create a memorable sound. Her playing has expanded to include electric explorations on a Gibson ES-175 and a Fender Stratocaster, in close coordination with a five-member band, while her voice has noticeably matured. She’s a long way from the bonier days of just “Freebo [her bassist from the beginning], my little dog Prune, a Matthews amp, and me.” In some ways. Upon the release of her sixth album, Sweet Forgiveness, Raitt does not deny her impatience for the long awaited, frustratingly elusive hit. Yet she maintains a unique hesitancy about making it big. Despite half-hearted forays into the realm of commercial appeal with her last two LPs, Streetlights and Home Plate, she seems to have returned to staunchly guarding her independence. Her most fervently expressed hopes focus on taking the blues into a new form; finding her own sound.

“I’ve been almost making it for a long time,” she says with traces of irony. “My records are never everything to everybody, but I’ve always got another chance to make something new. Once you have a hit, you’ve got to follow it up; that becomes your object or you won’t stay around.” Raitt is apparently not about to disappear from today’s music scene.

* * * *

How did you first learn to play slide?

I just broke off a wine bottle! Well, the style was called bottleneck, so I figured that’s what it was. The only problem was you couldn’t get wine bottles too easily if you didn’t drink, and at boarding school there weren’t a whole lot of wine-drinking orgies.

Were you still playing the Stella?

No, after the Stella I got a red Guild with gut strings. No idea of the model number, but I remember wanting the red one because everyone else had white-topped guitars, and the red one went with my hair. I thought it made me look like an Irish Setter. Later I saved up and bought my first Guild. I forget the number, but I always play an F-50 now. My first National was a copper-colored metal one but it was painted. They used to paint them to look like wood. The one I have now is around a 1929. It has a wooden body which is very unique.

Cambridge, Massachusetts, was a turning point for you. What happened there?

I went there to go to college. I just played guitar as a hobby, but I ran into a lot of blues freaks at the Harvard station, WHRB, and at Club 47 in Harvard Square, a major outlet for musicians like Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, Taj Mahal, and Canned Heat, not to mention John Hurt and Skip James. Strangely enough. I’d rushed to get old enough to catch this great Greenwich Village folk scene I’d heard about, and naturally the year I moved to Cambridge the club closed, and along came The Ultimate Spinach and acid rock. This whole incredible political scene went to pot, literally, but that’s when I met Dick Waterman.

By coincidence?

No, I was already a blues freak when I left California. There was a kind of blues mafia between New York, Philadelphia, and Cambridge—all these esoteric people talking about their blues idols’ eating habits, the obscure 78s they’d find, and Dick was a kind of liaison, but he was unique in his concern for taking care of artists who were still alive rather than trying to revive an era that was dead. Everyone at the Harvard station knew him, and if you wanted to do a blues show, you’d call Dick Waterman. Periodically Son House, Skip James, or Arthur Crudup would come to town. Anyway, one afternoon a friend of mine invited me to this apartment on Franklin Street, and who was there housesitting for Dick Waterman, but Son House. I was just floored. Then I began to meet them all.

All through Waterman?

Dick at the time managed Junior Wells, Buddy Guy, Magic Sam, Otis Rush, Luther Allison, J.B. Hutto, as well as many other traditional bluesmen. The reason it made sense to have so many under one agency was to protect them from the abuse of white blues promoters. Club owners would play one bluesman against the other. They’d say, “Well, we can get Bukka White for $200 less, so why bother with Son House?” Then Son’s manager would have to drop his price in order to get the guy a gig at all. Dick was outraged, and by keeping them all under one agency he could protect their rights. “You’re not going to get any of them to play unless you pay what they deserve,” he’d say. I started traveling around with Dick, driving Son, Skip, or Sleepy John Estes to the blues festivals, and I became real tight with them. With Buddy or Junior Wells, guys in their forties, that was fun, but with the older men friendship was difficult. John Hurt died right before I met Dick, and that was just the beginning of a series of five or six deaths, which was terribly painful for those who knew them. But still, meeting them and knowing them was overwhelming; I can’t describe it.

Of all these legendary figures, who influenced you the most?

That’s impossible to say. One of them had to be Fred McDowell, who stayed with Dick when he was in town. He thought it was really funny, this little eighteen-year-old girl playing guitar, but he was flattered at my interest, and he taught me. Also, I’d say I emulate Muddy Waters’ style.

Did you actually try to imitate him or any of the others?

Not exactly. You can’t help but learn if you sit and play music with somebody. It was like being stung with a guitar style, and I had to play that way, or else it didn’t feel good. It’s not like a singing style where you try to avoid sounding like someone else.

When did you develop confidence in playing ‘their’ style?

During my first gig with Taj Mahal one afternoon. I took out my National and started playing some Fred McDowell stuff, and Taj, who didn’t know me, looked over and said, “hey all right.” He came over, took out his guitar, and we started playing a wordless duet, him playing Willie Brown to my Charley Patton [both Delta blues figures]; you know, just throwing blues licks off each other, not saying anything. Finally he reached out his hand and said, “Hello, my name is Taj Mahal.” [Blues interpreter] John Hammond has been a great help to me. I had a crush on him for years. Being a girl helped. These musicians came in, heard me sounding—or trying to—just like them, and they’d be flattered, and helpful. If I’d been a young guy doing a show just like John Hammond’s, he might have felt a bit threatened. I wasn’t playing as good as them, but they were real tickled that I was into their style.

How did you develop your own style out of the traditional blues?

My style is probably the result of a problem. My voice, actually soprano, is around five keys up from where Robert Johnson or Son House would do a song, say in Spanish open G tuning. I can’t tune the strings up or down to get that open octave;

I have to capo up three or five frets to get the same tuning, which is the only way to make the guitar part sound good. You lose the octaves—with no cutaway you can’t get your hand up there, and you’ve got only around three frets left to play slide. My National has a new, hybrid neck with fourteen frets, and that’s one of the reasons I went to electric, for the longer neck. Just adding my voice to a Fred McDowell guitar part would bring about a unique style, though.

Do you have trouble with your voice?

As my throat doctor says, “You’re trying to sing that Afro style.” I lose my voice often, because I do push it a lot to sing more blues, soul, or R&B. It was hard to do “Walking Blues” (on Bonnie Raitt) for instance, but I was not born with a voice like Mavis Staples or [contemporary English blues singer] Jo Ann Kelly who sounds uncannily like Memphis Minnie, or any ballsy, chesty blueswoman. My voice is neo-Judy Collins.

You don’t really sound like her.

Well, I’ve beaten my voice down over the years by pickling it with alcohol and screaming and yelling, so it’s gotten lower. If I was to sit here and play some blues for you now, and not worry about singing, I’d play what I feel is real good. I’d have liked to play more Fred McDowell and Robert Johnson stuff, but I have kind of this bird voice. As I was learning how to sing in public, I found that putting the tune in my key took away a lot of beautiful positions. My style is not a B.B. King lead guitar solo style, but just kind of half rhythm, usually in the key of E or A drawn from Muddy Waters, Brownie McGhee, John Hammond, Fred McDowell. It limits what I can do. Instead of doing a song in D, like most guitarists who really know their way around the neck, I move the capo around because I don’t want to miss that Muddy Waters-type blues riff. That’s the only way I can get the sound I want.

Visitors Today : 103

Visitors Today : 103 Now Online : 2

Now Online : 2