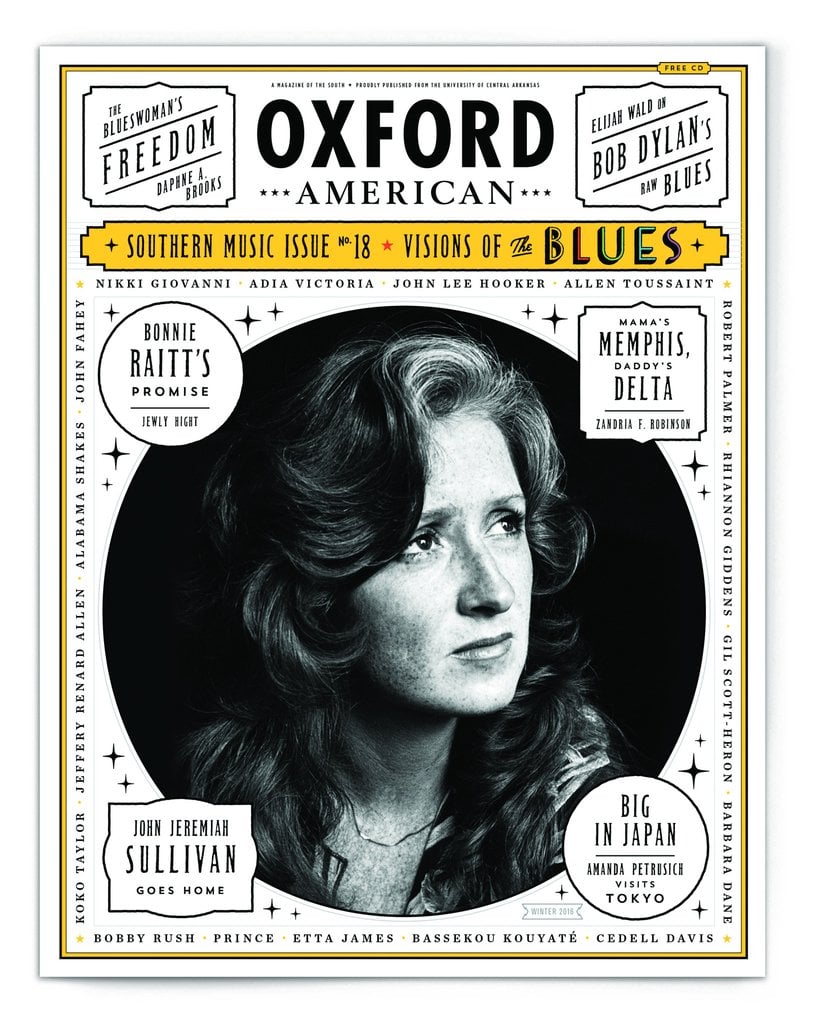

© Photo courtesy of Deborah Feingold / Corbis Premium Historial / Getty Images

I was halfway through college in South Florida when somebody burned me a copy of Luck of the Draw, Bonnie Raitt’s album released in 1991, by then a decade old. Trying not to disturb my roommates, I lay in bed listening through headphones, taken with how appealing this artist made adulthood sound—like she was sure on her feet, felt comfortable in her skin, and actually found it freeing, even fun, to act her age.

The first four tracks had her playing the part of a tease with her funky, anticipatory vocal phrasing; she sparred over domestic annoyances with what seemed like a knowing grin, cradled her heartbreak with exquisite tenderness, and relished the emotional risk and mutual satisfaction that comes with deepening a relationship. (“Gonna get into it / Down where it’s tangled and dark / Way on into it, baby / Down where your fears are parked.”) That was worlds away from the previews of womanhood I’d received elsewhere: at a mother-daughter tea party to which I’d been dragged in the sixth grade (an occasion to rehearse ladylike behavior), or at the church I attended with my folks (which, in its interpretation of Christian scripture, barred women from official leadership roles), or in my high school carpool with friends on the drill team (who carried themselves with the grace of lifelong ballet students, while I carried drumsticks, the lone girl on the marching band’s drumline). By those standards of femininity, I was clearly failing, but I wasn’t all that interested in trying to improve my performance.

Once Raitt got my attention, I started scouring the Rs at every new and used record store I passed, gradually collecting her entire catalog. When she played a West Palm Beach festival just a few miles from my apartment, I bought tickets for the whole weekend-long shebang but only braved the subtropical heat for her set, standing in line afterward to shell out twenty-five bucks for a Silver Lining tour t-shirt in a babydoll cut. A friend later pilfered the booklet from one of my Raitt CDs and had the cover photo blown up on posterboard so that an enlarged image of a young Bonnie wished me a helluva happy one at my twenty-first birthday party.

I was searching for a vision of womanhood that I didn’t find suffocating, so it was a real relief to have the likeness of a grown-ass woman like her around.

She’s been at it for four and a half decades now, yet Raitt’s perspectives on musical maturity and emotional truth-telling, and her simultaneous embrace of sensuality and smarts, have never seemed more relevant—and more admired. In February 2016, following the release of her seventeenth studio album, Dig in Deep, Raitt was interviewed for Lenny Letter, the newsletter for millennial feminists launched by Girls collaborators Lena Dunham and Jenni Konner. At a recent concert taping that paired Alicia Keys with Maren Morris—a twenty-six-year-old country-pop newcomer who delivers her songs from a frank, assured posture—Morris covered John Prine’s “Angel from Montgomery,” a country-blues lament of a woman wrung out by life, popularized by Raitt. When Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson, the creators of Broad City, extended their brazenly slackerish, sexually unencumbered television personas with a comedy tour, Glazer gave Raitt a shout-out from the stage. And in the sizable Americana scene—a community that grew up around roots-minded contemporary music-makers—Raitt has come to be celebrated as something of a godmother.

Raitt has been recording since she was twenty-one, when she retreated to a deserted summer camp in Minnesota with a freewheeling cast of musician-friends—including Freebo, an agile, long-haired bassist, and Chicago blues harpist Junior Wells, borrowed from Buddy Guy’s band—to knock out her self-titled debut. They emerged from their bucolic retreat with an earthy, rhythmically loose-limbed album.

Raitt had grown up spending summers in the care of beatnik college students at a Quaker camp in the Adirondack Mountains, absorbing their infatuation with the gravitas of lefty folk songs and learning to sing and strum like Joan Baez. Born in Burbank, California, to pianist Marjorie Haydock and Broadway star John Raitt (the couple later divorced), Bonnie was raised Quaker, a faith that valued conscientious modesty and a sensitivity to injustice. John Raitt’s career had also perched the family on the figurative and geographical edge of Hollywood. Bonnie watched her dad personify robust theatricality on stage; he was a classic leading man, projecting his regally rippling falsetto in Carousel, Oklahoma!, and The Pajama Game. By her early teens, she had fallen under the spell of the country bluesmen featured on Blues at Newport 1963, including Brownie McGhee, Sonny Terry, and John Lee Hooker. In 1967, she embarked on an immersive musical education when she started her freshman year at Radcliff and made the most of her proximity to the Cambridge folk scene. Raitt quickly fell in with, then began to date, Dick Waterman, a music photographer a decade and a half her senior who’d made it his mission to revive the long-dormant or languishing careers of blues elders like Mississippi Fred McDowell, Son House, Bukka White, Sippie Wallace, and Skip James.

Folk revivalists had often conceived of themselves as preservers of African-American musical traditions, a relationship that, as Jack Hamilton puts it in Just Around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination, “held black music and musicians to be engines of raw and unknowable power that existed almost exclusively in the past.” Raitt, on the other hand, recognized veteran blues performers’ modern ingenuity and highly developed technique, seizing the chance to study lyrical slide-guitar licks at McDowell’s feet. She signed with Warner Bros. after garnering buzz as his opener.

Though I’ve long been unfazed by speaking with superstars whose handlers aggressively micromanage their interactions, I was nervous as a newbie as I waited for Raitt to call me from her Northern California home, calming myself with meditative breathing exercises, one eye glued to my iPhone. Until that moment, I hadn’t given much thought to the fact that my fixation on her music had stayed with me since those collegiate experiences of unexamined fandom, before it became my job to place a critical frame around what I hear.

When my phone finally rang, I willed myself into a normal breathing pattern. Raitt marveled at how she’d lucked into hanging around with Waterman’s legendary clients. “I could have a conversation with Sippie Wallace or Fred McDowell and ask them what it was like to grow up under segregation and Jim Crow laws, and what it was like for Sippie to tour in those vaudeville tent shows, and, ‘What kind of discrimination did you experience? How did men treat you? And where did you learn to play cards?’”

Raitt had been on an overseas trek when she first stumbled upon a record by Wallace, a salty prewar jazz and blues singer and songwriter who’d recorded numerous sides for Okeh in the 1920s, then disappeared into church work in Detroit before reemerging on the blues revival circuit in the mid-1960s. By the time the two finally met, Raitt had cut three of Wallace’s originals, beginning with the swaggering number “Mighty Tight Woman.”

Raitt quoted a lyric from another Wallace number, “You Got to Know How”—“You can make me do what you wanna do, but you’ve got to know how”—then added, “That was a sly wink towards sexual proficiency, I’m sure, but also she meant all the way across the board, you know? Like, ‘I’m not gonna be your dog. You can’t order me ’round and you’d better know what you’re doing in bed. I’ll do what you want, but you’d better do what I want.’”

She was thrilled to find such sexually liberated attitudes in the repertoire of a singer and songwriter old enough to be her grandmother. “You Got to Know How” appeared on Raitt’s second album, Give It Up, released in 1972; she deployed Wallace’s lyrics to goad and instruct a would-be lover over a sauntering New Orleans groove. “One of the reasons I loved Sippie Wallace is because as a young feminist, when the feminist movement was completely exploding in my college years, the lyrics [to certain blues tunes] sometimes could be kinda misogynistic,” she reflected.

Hyperbolic boasts about domestic violence weren’t at all uncommon in country blues lyrics. After all, Big Bill Broonzy threatened to “use my fist” to keep his woman in line in “When I Been Drinkin’.” In “A to Z Blues,” Blind Willie McTell vowed to take a razor to a woman who’d dare leave him. “Kinda misogynistic” would be an understatement.

Raitt continued, “I can only pick songs that really go with what I feel, and it was really important to me to be treated with respect.”

But wait, there's more!

Visitors Today : 64

Visitors Today : 64 Now Online : 2

Now Online : 2